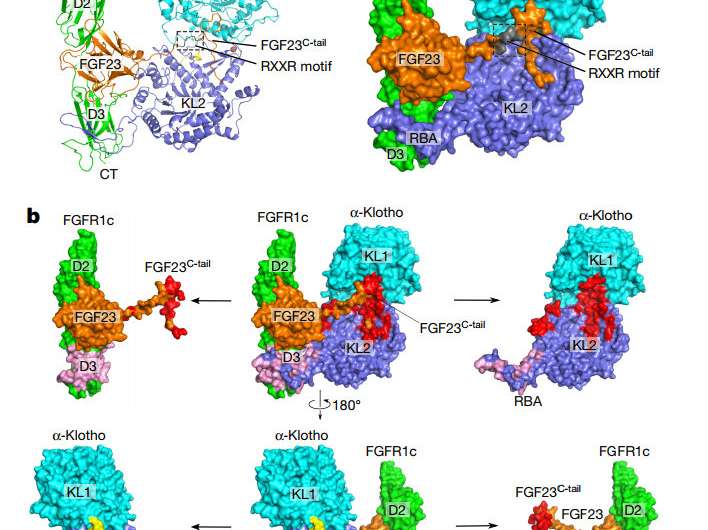

Overall topology of the FGF23–FGFR1cecto–α-klothoecto complex. a, Cartoon (left) and surface representation (right) of the ternary complex structure. The α-klotho KL1 (cyan) and KL2 (blue) domains are joined by a short proline-rich linker (yellow; not visible in the surface presentation). FGF23 is in orange with its proteolytic cleavage motif in grey. FGFR1c is in green. CT, C terminus; NT, N terminus. b, Binding interfaces between α-klothoecto and the FGF23–FGFR1cecto complex. The ternary complex (centre) is shown in two different orientations related by a 180° rotation along the vertical axis. FGF23–α-klothoecto (red) and FGFR1cecto– α-klothoecto (pink) interfaces are visualized by pulling α-klothoecto and the FGF23–FGFR1cecto complex away from each other. The separated components are shown to the left and right of the ternary complex. Credit: Nature (2018). DOI: 10.1038/nature25010

A new study reveals the molecular structure of a protein called alpha(α)Klotho, and how it helps to transmit a hormonal signal that slows aging.

Led by researchers from NYU School of Medicine and published online Jan. 17 in Nature, the study refutes 20 years of conjecture that αKlotho - named after the Greek goddess who spins the thread of life - is a major anti-aging hormone. Instead the results attribute this function to fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), and explain how αKlotho simply helps FGF23 to mediate its anti-aging action.

Studies as far back as 1997 had shown that mice genetically manipulated to lack either αKlotho or FGF23 suffered from premature aging, including early onset cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cognitive decline. By providing a first look at the structure of the associated group of proteins that includes FGF23, its receptor protein (FGFR), and αKlotho, the current study overturns the dogma that αKlotho acts on its own as a longevity factor.

"By showing that all the ways in which αKlotho was supposed to protect organs come instead from its ability to help FGF23 signal, we have shed new light on the underlying cause of aging," says lead study author Moosa Mohammadi, PhD, professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology at NYU Langone Health. "Our new structural data also pave the way for the design of novel agents that can either encourage or block FGF23-αKlotho signaling as needed."

Structure Solves Mystery

To determine the atomic structure of the FGF23 signaling group of proteins, Mohammadi and colleagues used X-ray crystallography. The team first coaxed the FGF23 hormone, along with its receptor protein (FGFR) and αKlotho, to settle out of a solution and form stacks of repeating, orderly crystals. They then exposed the crystals to X-rays, and used the reflected patterns to compute the atomic structure of the proteins.

The new study provides the first evidence of how FGF23 can only signal to cells by forming a complex with αKlotho, its receptor, and another partner in heparan sulfate. Made by bone cells, the FGF23 hormone is known to travel via the blood stream to cells in other organs, where it delivers its message by docking onto and turning on its receptor. The newly solved complex structure reveals how αKlotho tethers FGF23 to its receptor with enough tenacity to activate it.

The study also sheds new light on how kidney disease leads to an abnormal thickening of heart muscle tissue called hypertrophy. Heart hypertrophy is a leading cause of death in people with damaged kidney tubules, caused (for example) by high blood pressure and diabetes. When damaged kidney tubules can no longer adequately eliminate phosphate in the urine, FGF23 rises in an effort to keep blood phosphate in check, in part by controlling levels of vitamin D. A prevailing hypothesis has been that very high levels of FGF23 cause hypertrophy in the heart, but the theory remained controversial because heart tissue does not have αKlotho, which must be present if FGF23 is to signal.

Past studies had shown that the best known form of αKlotho is immobile, being bound to the surface membranes of cells in kidney tubules, the parathyroid gland, and certain regions of the brain. Then researchers learned that a part of the αKlotho protein that protrudes from cell surfaces, the ecto domain, can be cut off and shed into circulating bodily fluids, and therefore might reach the heart. Early evidence, however, suggested that shed αKlotho was incapable of acting as an FGF23 co-receptor. The new study integrates these observations by showing that circulating αKlotho can indeed function just like its membrane-bound form to enable FGF23 signaling.

The researchers say that their findings will launch another drug development race in kidney disease. Mohammadi had already shown that a key piece of the FGF23 hormone (its C-terminal tail peptide), when injected into mice, competes with intact FGF23 to reduce its signal and prevent heart hypertrophy. In addition, the team is already designing new molecules that alter the FGF23/shed αKlotho signal based on the newly discovered protein structures.

The study also suggests that a related protein, beta-Klotho, serves as the same kind of co-receptor to help FGF21, a hormone related to FGF23. FGF21 functions by sending signals that keep blood sugar and fatty acids in balance, with implications for diabetes and obesity.

More information: α-Klotho is a non-enzymatic molecular scaffold for FGF23 hormone signalling, Nature (2018). nature.com/articles/doi:10.1038/nature25451

Journal information: Nature

Provided by NYU Langone Health