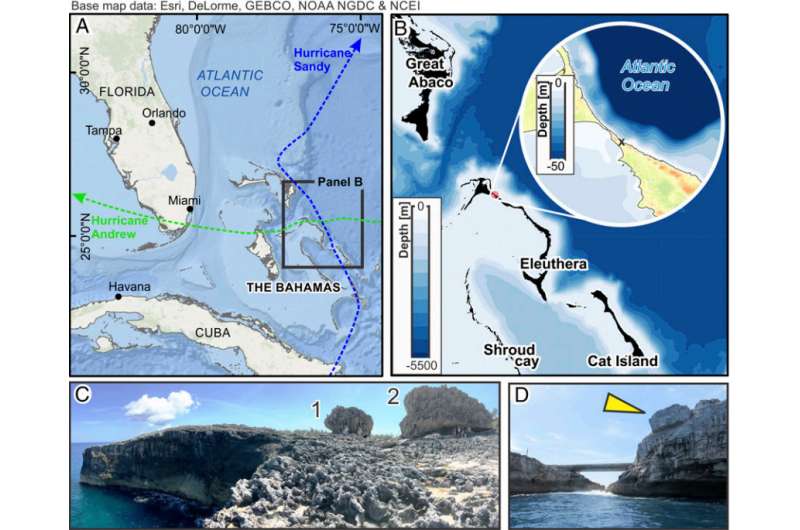

Geographic location of Glass Window Bridge and the Cow and Bull boulders, North Eleuthera, Bahamas. Credit: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2017). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1712433114

(Phys.org)—An international team of researchers has come up with a new theory to explain how two giant boulders could have made their way atop a cliff on the Bahamian island of Eleuthera. In their paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the group suggests that it would not have taken a super-storm, as some have suggested.

On the Bahamian island of Eleuthera there sit two massive boulders some distance from a cliff edge. Because the boulders were not formed where they are, logic suggests they must have come from somewhere else, likely pushed by the sea. The boulders, named simply "cow" and "bull," have been objects of interest for some time, but more recently, they have attracted the attention of climatologists because they may represent an ominous future.

Two years ago, a team led by Paul Hearty suggested that the two boulders, which each weigh hundreds of tons, made their way atop the cliff from below due to the power of a raging superstorm approximately 100,000 years ago—a time period during which sea levels were much higher than today due to a warmer climate. In this new effort, the researchers suggest it would it would not have taken a superstorm to move the giant boulders—their simulations suggest a storm on the order of Hurricane Sandy would be powerful enough to drive the boulders back from the cliff edge to their current position.

Both teams agree that the boulders likely formed on land below where they now sit, but they disagree on where that might have been. Hearty's team suggested they most likely came from a lower cliff. In the more recent effort, the group traveled to Eleuthera and took a lot of measurements of the boulders, the cliffs and the seafloor beyond the cliffs. They then used what they had found to calculate the approximate weight of the boulders, 383 and 925 tons respectively. With that information in hand, they were able to create simulations showing what sorts of waves would have enough power to push them around at different sea levels. They report their simulations showed waves moving at just 20 to 25 mph had enough energy in them to push the boulders back from the cliff edge, which is where the team claims they were likely formed—if sea levels were 20 to 30 feet higher than they are today.

More information: Alessio Rovere et al. Giant boulders and Last Interglacial storm intensity in the North Atlantic, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2017). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1712433114

Abstract

As global climate warms and sea level rises, coastal areas will be subject to more frequent extreme flooding and hurricanes. Geologic evidence for extreme coastal storms during past warm periods has the potential to provide fundamental insights into their future intensity. Recent studies argue that during the Last Interglacial (MIS 5e, ∼128–116 ka) tropical and extratropical North Atlantic cyclones may have been more intense than at present, and may have produced waves larger than those observed historically. Such strong swells are inferred to have created a number of geologic features that can be observed today along the coastlines of Bermuda and the Bahamas. In this paper, we investigate the most iconic among these features: massive boulders atop a cliff in North Eleuthera, Bahamas. We combine geologic field surveys, wave models, and boulder transport equations to test the hypothesis that such boulders must have been emplaced by storms of greater-than-historical intensity. By contrast, our results suggest that with the higher relative sea level (RSL) estimated for the Bahamas during MIS 5e, boulders of this size could have been transported by waves generated by storms of historical intensity. Thus, while the megaboulders of Eleuthera cannot be used as geologic proof for past "superstorms," they do show that with rising sea levels, cliffs and coastal barriers will be subject to significantly greater erosional energy, even without changes in storm intensity.

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

© 2017 Phys.org