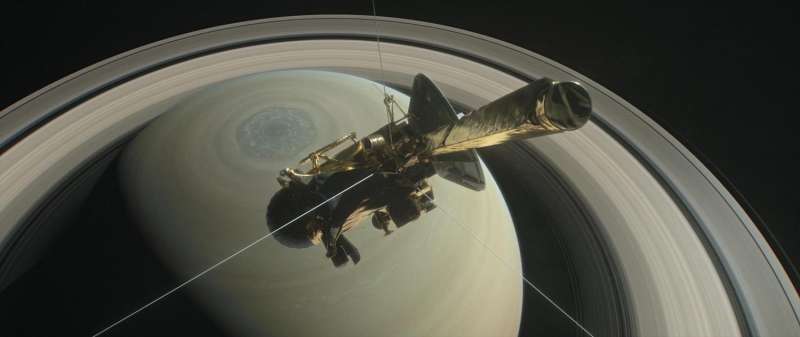

This illustration shows Cassini above Saturn's northern hemisphere prior to one of its 22 Grand Finale dives. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

In the dark of the early morning, planetary scientist Andy Ingersoll stood alone and slightly stooped at a coffee cart at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. More than 900 million miles across the solar system, the 2-ton Cassini spacecraft that he worked on for more than 20 years was being ripped apart and vaporizing in the cloud tops of Saturn.

"I'm just going to fortify myself with caffeine and some sugar," Ingersoll said.

He was here at JPL in La Canada Flintridge to await the final signal from the spacecraft that has spent the past 13 years exploring the Saturnian system - the planet, its rings and its moons.

Ingersoll, a Caltech professor who also worked on NASA's Pioneer, Voyager and Galileo missions, said he wasn't feeling particularly sad.

"I'm just thinking how lucky I am," he said. "I feel so grateful to the planets themselves. They have provided so many more surprises and fantastic stuff than we ever expected."

It took 1 hour and 23 minutes for news of Cassini's fate to reach Earth. It finally arrived at NASA's Deep Space Communication Complex in Canberra, Australia, just before 5 a.m. Pacific time Friday.

Roughly two dozen people sat in the mission control room looking grim and passing around a canister of peanuts as they awaited the final transmission.

When the green radio signal flatlined, Cassini program manager Earl Maize had the somber duty of announcing that humanity's grand adventure to Saturn had come to a close.

"I hope you are all as deeply proud of this accomplishment as I am," he said. "I'm going to call this: 'End of mission. Program manager off the net.'"

The room erupted in clapping, but there was not much smiling.

Sherwin Goo, who has been a member of the Cassini flight team since a year and half before its launch in October 1997, said he was feeling a mixture of pride, happiness and sadness.

"I've been flying with this group of people for 20 years," he said. "We're a family."

About 30 minutes after Cassini had been officially declared dead, Jo Pitesky, a project science engineer who worked on the mission for 16 years, said she was still in denial.

"There have been times over the past week when I've just been sobbing," she said with her eyes still dry. "I expect that will come later."

Pitesky said she has been talking to friends in the clergy about how to create a ritual that would honor the death of the two-story machine.

"How do you mark this?" she said.

She still has more work to do on the Cassini mission. For the next year, she will be making sure that all the data Cassini collected will get into the hands of researchers who will study it for generations to come.

"What was a $3.6 billion spacecraft is now a $3.6 billion science legacy," she said.

©2017 Los Angeles Times

Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.