Shell researchers collected samples from oil wells in a North Sea oil field like this one. Credit: Berardo62, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0

Microbes are invisible to the naked eye, but play key roles in maintaining the planet's biogeochemical cycles. In the Earth's subsurface, microbes have adapted to thrive in the relatively stable extreme conditions. To learn more about how some of these populations respond to disruptions in their environment, researchers in the petroleum industry conducted a comparative genetic analysis of the microbial communities in multiple oil wells within an offshore oil field. The analysis utilized tools developed at the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (DOE JGI), a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

While shifting toward more sustainable, alternative energy sources, people still rely on fossil fuels for energy and transportation fuels. Understanding how microbial communities in subsurface petroleum reservoirs are impacted by human activity, and how their responses can sour oil production, can influence oil industry practices. Harnessing capabilities made available through DOE JGI's publicly accessible data analysis system afforded industry researchers insights into the interactions between reservoir conditions and microbial community composition.

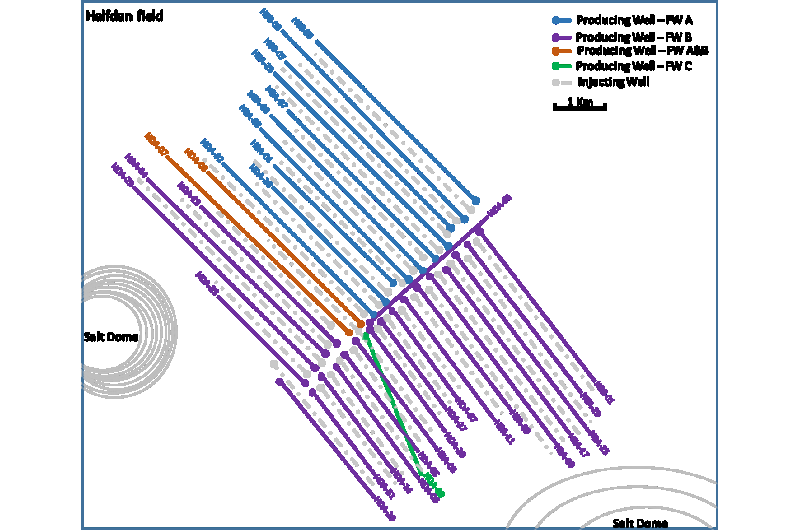

In the North Sea is an offshore petroleum reservoir managed by a joint venture of which Shell, one of the world's largest oil companies, is a partner. Over the past 15 years, 32 oil wells have been drilled, reaching depths over 2 kilometers below the seafloor to extract petroleum from this deep subsurface reservoir. Recovering gas and oil for energy and transportation fuels impacts the previously isolated microbial communities in the deep subsurface. For example, water injections introduce new microbes to the existing indigenous populations, which can lead to the production of the highly toxic and corrosive hydrogen sulfide, impacting oil well productivity and oil quality.

Schematic of Halfdan Oil Field. Credit: Nicolas Tsesmetzis

To learn more about the composition of these microbial communities, Shell researchers, in collaboration with DOE JGI and Newcastle University in the United Kingdom, analyzed samples from the 32 oil wells of the Halfdan North Sea oil field (owned by Denmark) and tracked the succession of microbial populations in multiple oil wells drilled at different times in an offshore, deep subsurface petroleum reservoir. They sequenced the samples and then analyzed the data to learn about community compositions, and how these compositions change over time the longer an oil well stays in production mode. During the analyses, tools developed at the DOE JGI and made available through the Integrated Microbial Genomes and Metagenomes (IMG/M) system were utilized. The data generated provides insights into just how deep subsurface microbial communities are perturbed by active oil wells injecting foreign substances into these previously isolated populations, and helps industry researchers develop new techniques for managing microbiological problems.

"For the first time, we are able to shed light into this remote and largely unexplored ecosystem" said study senior author Nicolas Tsesmetzis of Shell International Exploration and Production Inc. "The largely heterogeneous and highly diverse microbial communities recovered from the different oil wells of the same oil field was rather unexpected and brings about a paradigm shift in our standard microbial monitoring practices of petroleum systems." This work indicates that the microbial communities in these drill sites are more diverse and dynamic than was expected, as well as more responsive to drilling activities.

The work was reported in The ISME Journal.

More information: Adrien Vigneron et al. Succession in the petroleum reservoir microbiome through an oil field production lifecycle, The ISME Journal (2017). DOI: 10.1038/ismej.2017.78

Journal information: ISME Journal

Provided by DOE/Joint Genome Institute