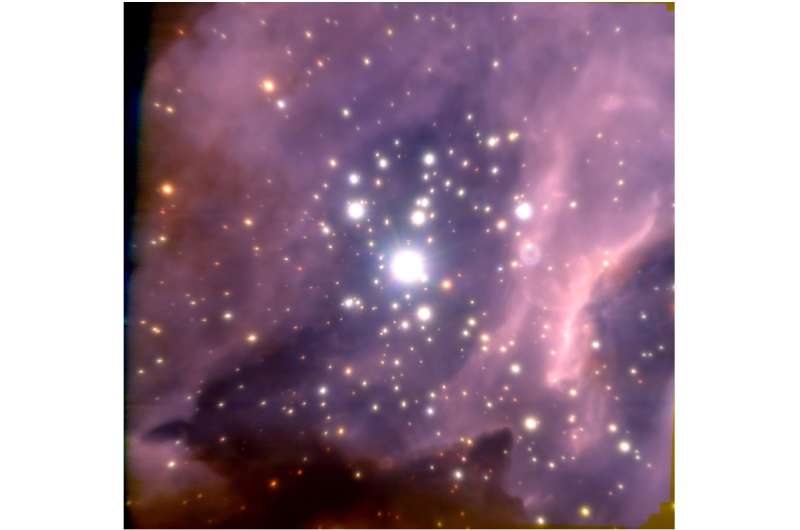

A false-color near-infrared image of the core of the young massive cluster RCW 38 taken with the adaptive-optics camera NACO at the ESO's Very Large Telescope. RCW 38 lies at a distance of about 5500 light years from the Sun. The field of view of the central image is approximately 1 arc minute, or 1.5 light years across. The insets, each spanning about 0.07 light years on a side, show a subset of the faintest and least massive cluster candidate brown dwarfs (indicated by arrows) of RCW 38 discovered in this new image. These candidate brown dwarfs might weigh only a few tens of Jupiter masses, or about 100 times less than the most massive stars seen towards the centre of the image. Credit: Koraljka Muzic, University of Lisbon, Portugal / Aleks Scholz, University of St Andrews, UK / Rainer Schoedel, University of Granada, Spain / Vincent Geers, UKATC / Ray Jayawardhana, York University, Canada / Joana Ascenso, University of Lisbon, University of Porto, Portugal / Lucas Cieza, University Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile. The study is based on observations conducted with the VLT at the European Southern Observatory.

Our galaxy could have 100 billion brown dwarfs or more, according to work by an international team of astronomers, led by Koraljka Muzic from the University of Lisbon and Aleks Scholz from the University of St Andrews. On Thursday 6 July Scholz will present their survey of dense star clusters, where brown dwarfs are abundant, at the National Astronomy Meeting at the University of Hull.

Brown dwarfs are objects intermediate in mass between stars and planets, with masses too low to sustain stable hydrogen fusion in their core, the hallmark of stars like the Sun. After the initial discovery of brown dwarfs in 1995, scientists quickly realised that they are a natural by-product of processes that primarily lead to the formation of stars and planets.

All of the thousands of brown dwarfs found so far are relatively close to the Sun, the overwhelming majority within 1500 light years, simply because these objects are faint and therefore difficult to observe. Most of those detected are located in nearby star forming regions, which are all fairly small and have a low density of stars.

In 2006 the team began a new search for brown dwarfs, observing five nearby star forming regions. The Substellar Objects in Nearby Young Clusters (SONYC) survey included the star cluster NGC 1333, 1000 light years away in the constellation of Perseus. That object had about half as many brown dwarfs as stars, a higher proportion than seen before.

A false-color near-infrared image of the core of the young massive cluster RCW 38 taken with the adaptive-optics camera NACO at the ESO's Very Large Telescope. RCW 38 lies at a distance of about 5500 light years from the Sun. The field of view of the central image is approximately 1 arc minute, or 1.5 light years across. Credit: Koraljka Muzic, University of Lisbon, Portugal / Aleks Scholz, University of St Andrews, UK / Rainer Schoedel, University of Granada, Spain / Vincent Geers, UKATC / Ray Jayawardhana, York University, Canada / Joana Ascenso, University of Lisbon, University of Porto, Portugal / Lucas Cieza, University Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile. The study is based on observations conducted with the VLT at the European Southern Observatory.

To establish whether NGC 1333 was unusual, in 2016 the team turned to another more distant star cluster, RCW 38, in the constellation of Vela. This has a high density of more massive stars, and very different conditions to other clusters.

RCW 38 is 5500 light years away, meaning that the brown dwarfs are both faint, and hard to pick out next to the brighter stars. To get a clear image, Scholz, Muzic and their collaborators used the NACO adaptive optics camera on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope, observing the cluster for a total of 3 hours, and combining this with earlier work.

The researchers found just as many brown dwarfs in RCW 38 - about half as many as there are stars - and realised that the environment where the stars form, whether stars are more or less massive, tightly packed or less crowded, has only a small effect on how brown dwarfs form.

Artist's impression of a T-type brown dwarf. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Scholz says: "We've found a lot of brown dwarfs in these clusters. And whatever the cluster type, the brown dwarfs are really common. Brown dwarfs form alongside stars in clusters, so our work suggests there are a huge number of brown dwarfs out there."

From the SONYC survey, Scholz and team leader Koraljka Muzic, estimate that our galaxy, the Milky Way, has a minimum of between 25 and 100 billion brown dwarfs. There are many smaller, fainter brown dwarfs too, so this could be a significant underestimate, and the survey confirms these dim objects are ubiquitous.

More information: The new work appears in: "The low-mass content of the massive young star cluster RCW 38", K. Muzic, R. Schoedel, A. Scholz, V. C. Geers, R. Jayawardhana, J. Ascenso, and L. A. Cieza, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, submitted.

The results will be presented as part of a talk at NAM2017 by co-author and SONYC lead Aleks Scholz on Thursday 6 July.

Journal information: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Provided by Royal Astronomical Society