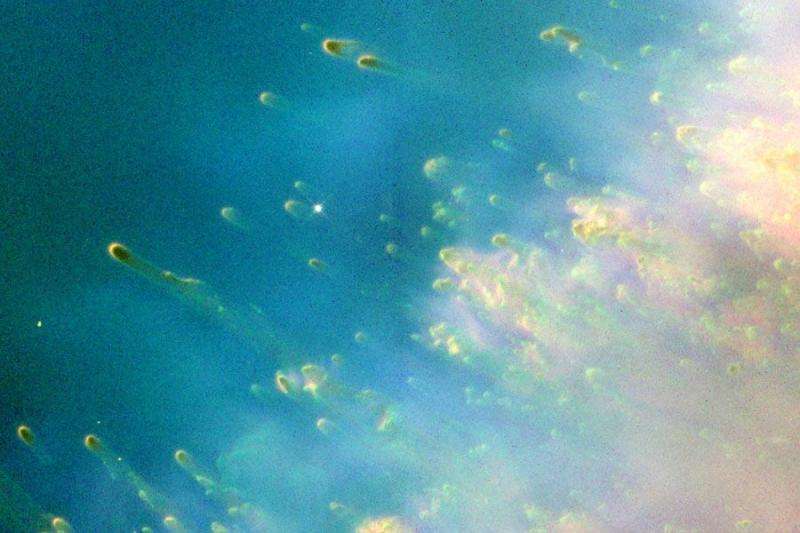

Schematic graphic of quasar twinkling. Credit: M. Walker (artwork), CSIRO (photo)

Gas filaments surrounding stars like the strands of a pompom may be the answer to a 30-year old mystery: why quasars twinkle.

Dr Mark Walker (Manly Astrophysics) and collaborators at Caltech, Manly Astrophysics and CSIRO (the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) published this solution today in the Astrophysical Journal.

Their evidence comes from research done with CSIRO's Compact Array radio telescope in eastern Australia.

Walker's team was studying quasars – powerful, distant galaxies – when they saw one called PKS 1322–110 start to dim and brighten wildly at radio wavelengths over just a few hours.

"This quasar was twinkling violently," Walker said.

Quasar radio twinkling was recognized in the 1980s. Most often it is gentle – small, slow changes in radio brightness. Violent twinkling is rare and unpredictable.

Stars in the night sky twinkle when currents of air in our atmosphere focus and defocus their light. In the same way, quasars twinkle when streams of warm gas in interstellar space focus and defocus their radio signals.

But until now it was a mystery what those streams were and where they lay.

The first sign that stars are involved came when the team prepared to look at their twinkling quasar, PKS 1322–110, with one of the 10-m Keck optical telescopes in Hawai'i.

"At that point we realised this quasar is very close on the sky to the hot star Spica," co-author Dr Vikram Ravi (Caltech) said.

Globules of hydrogen gas in the Helix Nebula, imaged with the Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: C. R. O'Dell (Vanderbilt University), K. Handron (Rice University), NASA

Walker remembered that another violently twinkling quasar, J1819+3845, is close on the sky to the hot star Vega – something previously noted by other researchers. Two hot stars, two twinkling quasars: is this just a coincidence?

Further work suggested it's not.

Walker's team re-examined earlier data on J1819+3845 and another violent twinkler, PKS 1257–326. They found that this second quasar lies close on the sky to a hot star called Alhakim.

The chance of having both twinkling quasars near hot stars is one in ten million, the researchers calculated.

"We have very detailed observations of these two sources," co-author Dr Hayley Bignall (CSIRO) said. "They show that the twinkling is caused by long, thin structures."

The team suggests that every hot star is surrounded by a throng of warm gas filaments, all pointing towards it.

"We think these stars look like the Helix Nebula," Walker said.

In the Helix a star sits in a swarm of cool globules of molecular hydrogen gas, each about as big as our solar system. Ultraviolet radiation from the star blasts the globules, giving each one a skin of warm gas and a long gas tail flowing outwards.

The star in the Helix is in its death throes, and astronomers usually assume that the globules arose late in the star's life. But Walker thinks such globules might be present around younger, mainstream stars. "They might date from when the stars formed, or even earlier," he said.

"Globules don't emit much light, so they could be common yet have escaped notice so far," he added.

"Now we'll turn over every rock to find more signs of them."

More information: Walker, M.A. and seven co-authors. "Extreme radio-wave scattering associated with hot stars." Astrophysical Journal, Volume 843, 27th June 2017. www.manlyastrophysics.org/Mate … apers/2017Walker.pdf

Journal information: Astrophysical Journal

Provided by Manly Astrophysics