Saprolite, is chemically weathered rock that scientists collected from several sites in Scandinavia, including this outcrop in Ivö, Sweden. Picture from paper. Credit: University of Tromso

Earth's bedrock was severely beaten by hothouse climate conditions during one of the planet's mass extinctions some 200 million years ago. But the process also allowed life to bounce back.

One of the Big Five mass extinction events occurred some 200 million years ago. Giant volcanic eruptions and an asteroid impact have been blamed for causing disastrous climate change, killing off nearly half of the species on Earth.

This epoch is called the Late Triassic. Amounts of carbon dioxide released through the volcanic activity during this period were staggering. Concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere were around 1000 ppm due to volcanic activity. For comparison, we have only recently reached 410 ppm of CO2 in the atmosphere today, a concentration that worries many scientists.

"In addition to the warming effects of the CO2 release, dissociation of massive amounts of methane hydrates had intensified the warming effect during the mass extinction," says Jochen Knies of CAGE and Geological Survey of Norway. He is a coauthor on recent Nature Communications study that found evidence of the impact of hothouse climate conditions during the Late Triassic in Scandinavia.

Precisely dating deeply impacted bedrock

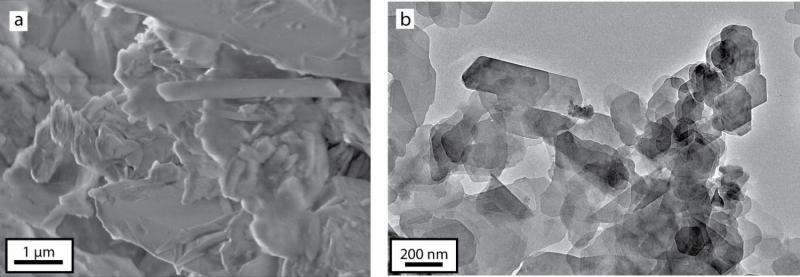

Microscopic images of illite, a clay mineral that forms by chemical weathering of bedrock, found in a well in Norwegian offshore petroleum province Utsira High, North Sea. Credit: University of Tromso

These new findings shed light on how high greenhouse gas concentrations caused the bedrock to disintegrate through chemical weathering. Chemical weathering is caused by water reacting with the mineral grains in rocks to form new minerals, such as clay mineral illite. These reactions occur particularly when the water is acidic, as is the case when the CO2 levels are high.

"We have managed to precisely date deeply weathered crystalline bedrock from the North Sea and across Scandinavia, which was then part of the supercontinent Pangea. We did this by detailed geomorphological and mineralogical analyses of weathered rocks combined with the dating of clay mineral illite," says Knies.

All the dated samples show that intensive and widespread chemical weathering occurred under hothouse conditions during the late Triassic. The bedrock was slowly transformed, and the transformation co-occurred with emerging volcanic activity.

Bedrock eventually removes CO2

The hothouse conditions of this mass extinction eventually depleted oceans of oxygen, a condition that could not support life. But weathering of silicate in the bedrock of Pangea and subsequent formation of carbonate trapped the CO2 in the minerals, slowly removing the greenhouse gas from the atmosphere.

"Transport of loose material toward the ocean may have ended life through the formation of oxygen-depleted waters and helped life recover through stabilization of the greenhouse effect through CO2 removal," says Knies.

More information: Ola Fredin et al. The inheritance of a Mesozoic landscape in western Scandinavia, Nature Communications (2017). DOI: 10.1038/ncomms14879

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by University of Tromso