April 7, 2017 feature

New insight into proving math's million-dollar problem: the Riemann hypothesis (Update)

(Phys.org)—Researchers have discovered that the solutions to a famous mathematical function called the Riemann zeta function correspond to the solutions of another, different kind of function that may make it easier to solve one of the biggest problems in mathematics: the Riemann hypothesis. If the results can be rigorously verified, then it would finally prove the Riemann hypothesis, which is worth a $1,000,000 Millennium Prize from the Clay Mathematics Institute.

While the Riemann hypothesis dates back to 1859, for the past 100 years or so mathematicians have been trying to find an operator function like the one discovered here, as it is considered a key step in the proof.

"To our knowledge, this is the first time that an explicit—and perhaps surprisingly relatively simple—operator has been identified whose eigenvalues ['solutions' in matrix terminology] correspond exactly to the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function," Dorje Brody, a mathematical physicist at Brunel University London and coauthor of the new study, told Phys.org.

What still remains to be proven is the second key step: that all of the eigenvalues are real numbers rather than imaginary ones. If future work can prove this, then it would finally prove the Riemann hypothesis.

Brody and his coauthors, mathematical physicists Carl Bender of Washington University in St. Louis and Markus Müller of the University of Western Ontario, have published their work in a recent issue of Physical Review Letters.

Spacing of primes

The Riemann hypothesis holds such a strong allure because it is deeply connected to number theory and, in particular, the prime numbers. In his 1859 paper, German mathematician Bernhard Riemann investigated the distribution of the prime numbers—or more precisely, the problem "given an integer N, how many prime numbers are there that are smaller than N?"

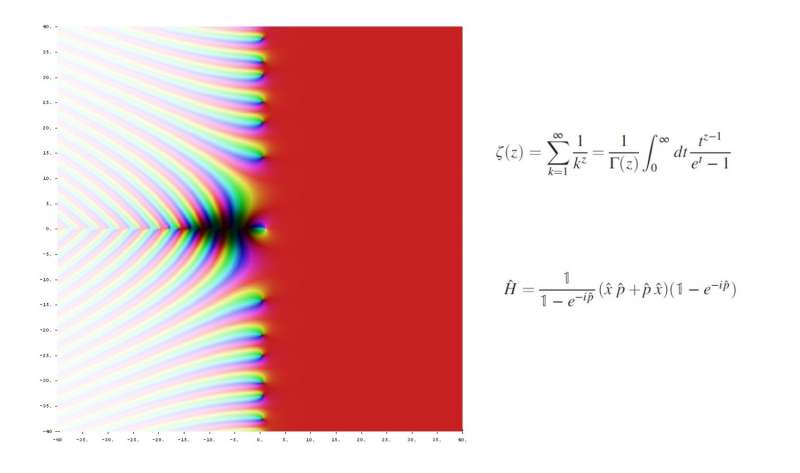

Riemann conjectured that the distribution of the prime numbers smaller than N is related to the nontrivial zeros of what's now called the Riemann zeta function, ζ(s). (The zeros are the solutions, or the values of s that make the function equal to zero. Although it was easy for mathematicians to see that there are zeros whenever s is a negative even number, these zeros are considered trivial zeros and are not the interesting part of the function.)

Riemann's hypothesis was that all of the nontrivial zeros lie along a single vertical line (½ + it) in the complex plane—meaning their real component is always ½, while their imaginary component i varies as you go up and down the line.

Over the past 150 years, mathematicians have found literally trillions of nontrivial zeros, and all of them have a real of component of ½, just as Riemann thought. It's widely believed that the Riemann hypothesis is true, and much work has been done based on this assumption. But despite intensive efforts, the Riemann hypothesis—that all of the infinitely many zeros lie on this single line—has not yet been proved.

Identical solutions

One of the most helpful clues for proving the Riemann hypothesis has come from function theory, which reveals that the values of the imaginary part, t, at which the function vanishes are discrete numbers. This suggests that the nontrivial zeros form a set of real and discrete numbers, which is just like the eigenvalues of another function called a differential operator, which is widely used in physics.

In the early 1900s, this similarity led some mathematicians to wonder whether there really exists a differential operator whose eigenvalues correspond exactly to the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function. Today this idea is called the Hilbert-Pólya conjecture, named after David Hilbert and George Pólya—despite the fact that neither of them published anything about it.

"Since there is no publication by Hilbert or Pólya, the exact statement of the Hilbert-Pólya program is subject to some extent to interpretation, but it is probably not unreasonable to say that it consists of two steps: (a) find an operator whose eigenvalues correspond to the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function; and (b) determine whether the eigenvalues are real," Brody said.

"The main focus of our work so far has been on step (a)," he said. "We have identified an operator whose eigenvalues correspond exactly to the nontrivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function. We are only beginning to think about step (b), and indeed how to tackle this challenge. Whether it will be difficult or easy to fill in the missing steps toward step (b), at this point we cannot speculate—further work is needed to get a better feeling as to the scale of difficulty involved."

The operator

One of the interesting things about the newly discovered operator is that it has close ties with quantum physics.

In 1999, when mathematical physicists Michael Berry and Jonathan Keating were investigating the Hilbert-Pólya conjecture, they made another important conjecture. If such an operator exists, they said, then it should correspond to a theoretical quantum system with particular properties. This is now called the Berry-Keating conjecture. But no one has ever found such a system before now, and this is a second important aspect of the new work.

"We have identified a quantization condition for the Berry-Keating Hamiltonian, thus essentially verifying the validity of the Berry-Keating conjecture," Brody said.

Hamiltonians are often used to describe the energy of physical systems. The new operator, however, doesn't appear to describe any physical system, but is rather a purely mathematical function.

"It may be disappointing, but such a Hamiltonian does not seem to represent physical systems in any obvious way; or at least so far we found no indication that our Hamiltonian corresponds to any physical system," Brody said.

"But one might then ask 'why publish in PRL?' The answer is because many of the techniques used for some heuristic analysis in our paper that are suggestive are borrowed from techniques of pseudo-Hermitian PT-symmetric quantum theory developed over the past 15 years or so. The conventional understanding of the Hilbert-Pólya conjecture is that the operator (Hamiltonian) should be Hermitian, and one naturally links this to quantum theory whereby Hamiltonians are conventionally demanded to be Hermitian. We are proposing a pseudo-Hermitian form of the Hilbert-Pólya program, which to us seems worthwhile exploring further."

Real solutions

Now the biggest challenge that remains is to show that the operator's eigenvalues are real numbers.

In general, the researchers are optimistic that the eigenvalues are actually real, and in their paper they present a strong argument for this based on PT symmetry, a concept from quantum physics. Basically, PT symmetry says that you can change the signs of all four components of space-time (three space or "parity" dimensions and one time dimension), and, if the system is PT-symmetric, then the result will look the same as the original.

Although nature in general is not PT-symmetric, the operator that the physicists constructed is. But now the researchers want to show that this symmetry gets broken. As they explain in their paper, if it can be shown that the PT symmetry is broken for the imaginary part of the operator, then it would follow that the eigenvalues are all real numbers, which would finally constitute the long-awaited proof of the Riemann hypothesis.

It's generally considered that a proof of the Riemann hypothesis will be very useful in computer science, especially cryptography. The researchers also want to determine what their results might actually mean for understanding more fundamental mathematical principles.

"What we have explored so far contains little number-theoretic insights; whereas one might expect that, given its importance in number theory, surely any attempt that successfully makes progress on establishing the Riemann hypothesis would offer number-theoretic insights," Brody said. "Of course this need not be the case at all, but nevertheless it would be of interest to explore whether any of the dynamical aspects of the hypothetical system described by our Hamiltonian might be linked to certain number-theoretic results. In this regard, semi-classical analysis on our Hamiltonian would be one of the next objectives."

More information: Carl M. Bender, Dorje C. Brody, and Markus P. Müller. "Hamiltonian for the Zeros of the Riemann Zeta Function." Physical Review Letters. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.130201

Journal information: Physical Review Letters

© 2017 Phys.org