Third gender defies image of macho Mexico

There is a popular myth told in the city of Juchitán, Mexico, to explain the prevalence and acceptance of indigenous men who consider themselves to be neither male nor female, but a hybrid third gender. It goes something like this:

God entrusted San Vicente, the patron saint of Juchitán, with three sacks of human beings: One was filled with women, one with men, and one with a third, mixed gender. Vicente was supposed to distribute these people evenly around the world. But when he got to Juchitán, the sack containing the hybrid gender ripped open and the region received more than its allotment of third-gender people.

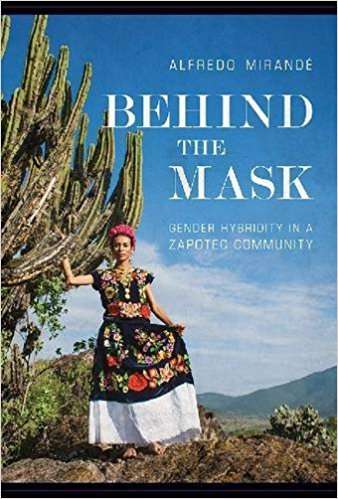

Hybrid-gender Zapotec men – known as los muxes – are the subject of a new book by University of California, Riverside scholar Alfredo Mirandé, "Behind the Mask: Gender Hybridity in a Zapotec Community" (University of Arizona Press, March 2017).

Muxes challenge the image of Mexico as a male-dominated land of machismo and homophobia, Mirandé said. Over a span of seven years, the sociologist interviewed muxes and community residents and leaders in Juchitán, a city of nearly 75,000 people in the state of Oaxaca, approximately 425 miles east of Acapulco on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

Los muxes are technically gay in that they have sexual relationships with other men, but they live their lives dressed as women – mostly in traditional, feminine, Zapotec attire – and adopt feminine behaviors. They distinguish themselves from gay men and transvestites, however, and consider themselves a third gender, Mirandé said.

"Muxes separate sexuality from gender. They have sex with hombres, 'real' men, not with each other," he said. "They challenge stereotypes about gender and machismo. In Mexico, traditionally, if you're the dominant one in a same-sex relationship, you're 'straight.' If you're passive, you're 'gay.' This is why macho men in Mexico can have sex with other men and not be gay. Muxes are always passive in these relationships."

Mirandé said he became interested in los muxes in 2008 when his daughter filmed a muxe vela, a festival, in Oaxaca and sent the recording to him.

"I was intrigued," said the distinguished professor of ethnic studies and sociology, who studies gender and masculinity.

Velas are important in Zapotec culture, and are organized by groups or societies dedicated to a saint, a family member, an occupation, or a neighborhood. They are expensive to produce and are representative of an economy where prestige is based, in part, on public displays of generosity.

That many muxes have the financial means and willingness to host velas is a sign of their acceptance in society and the economy, Mirandé said. The vela presented by the oldest muxe organization in Juchitán, Las Auténticas Intrépidas Buscadoras del Peligro (The Authentic, Fearless Seekers of Danger), is held in November and draws approximately 5,000 people. It includes a community festival and the Regada de Frutas (Tossing of the Fruit) on Friday, a Saturday morning Mass and an evening dance, and more relaxed festivities on Sunday afternoon that include the Lavada de Ollas (Washing the Pots).

Intrépidas may have as many as 100 members, about 40 of whom are wealthy enough to host an invitation-only gathering place, or puesto, in the vela, where the price of admission is a case of beer. Intrépidas members want to protect Zapotec traditions, dress, and language, and distinguish themselves from newer muxe groups whose members typically dress in high-fashion attire and eschew expensive velas.

Nobody knows when muxes started or how many there are, but most families in Juchitán have a muxe member. Muxes are especially accepted in the poorer and most indigenous sections of the city.

"Acceptance of muxe as a third gender is ancient, and may be traced to accounts of cross-dressing Aztec priests and Mayan gods who were at once male and female," Mirandé wrote in "Behind the Mask." Muxe is a Zapotec word apparently derived from the Spanish word for woman, which means effeminate.

Many of the more than 50 muxe the sociologist interviewed said they always knew they were muxe. Some were encouraged by their mothers from a young age to become muxe, considering them a "blessing from God" who would help around the house and care for their elderly parents.

Despite their wide acceptance in Juchitán, however, several muxes told Mirandé that their fathers could not cope with the loss of a macho son. "The difference between the popular conception of muxes as a blessing from God contrasted with the many realities of fathers rejecting and beating their muxe sons," Mirandé said.

Even so, one reason that muxes are so accepted in Juchitán relates to the role of women in Zapotec society, he said. Zapotec women are renowned as hard-working – so much so that it is a compliment to tell a man that he works as hard as a woman – and control the central market and households. Like women, muxes have a well-deserved reputation for being hard workers, skilled artisans, and successful merchants, he explained.

Also, Zapotec culture "is very familistic," Mirandé wrote. "Muxe children are accepted not because they are muxe per se, but because they are part of the family."

Provided by University of California - Riverside