Biologists discover timesharing strategy in bacteria

Timesharing, researchers have found, isn't only for vacation properties.

While the idea of splitting getaway condos in exotic destinations among various owners has been popular in real estate for decades, biologists at the University of California San Diego have discovered that communities of bacteria have been employing a similar strategy for millions of years.

Researchers in molecular biologist Gürol Süel's laboratory in UC San Diego's Division of Biological Sciences, along with colleagues at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Spain, asked what competing communities of bacteria might do when food becomes scarce. The team found that bacteria faced with limited nutrients will enter an elegant timesharing strategy in which communities alternate feeding periods to maximize efficiency in consumption. The study is published April 6 in the journal Science.

"What's interesting here is that you have these simple, single-celled bacteria that are tiny and seem to be lonely creatures, but in a community, they start to exhibit very dynamic and complex behaviors you would attribute to more sophisticated organisms or a social network," said Süel, associate director of the San Diego Center for Systems Biology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute - Simons Faculty Scholar at UC San Diego. "It's the same timesharing concept used in computer science, vacation homes and a lot of social applications."

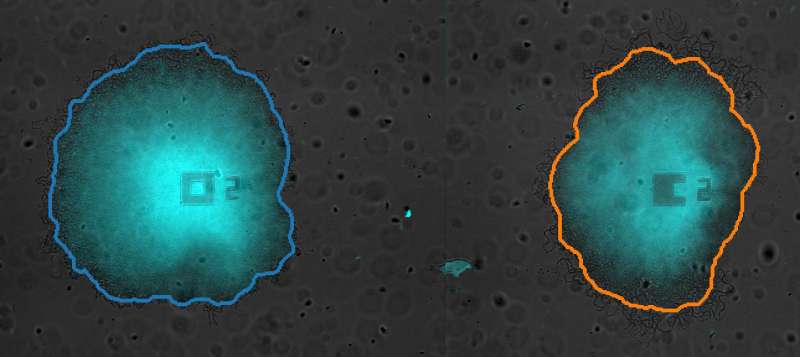

In January, Süel and his colleagues discovered that structured communities of bacteria, or "biofilms," use electrical signals to communicate with and recruit neighboring bacterial species. The new study investigates how two biofilm communities interact. Through mathematical models and laboratory evidence using microfluidic techniques and time-lapse microscopy, the researchers found that nearby biofilm communities will engage in synchronized behaviors through these electrical signals.

The experiments revealed that when biofilms faced scenarios of limited amounts of nutrients, they began to alternate their feeding periods to reduce competition and avoid "traffic jams" of consumption.

"It is common for living systems to operate in unison, but here we're showing that working out-of-sync can also provide a biological benefit," said Jordi Garcia-Ojalvo, professor of systems biology at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain, and co-author of the study.

"These bacteria are just about everywhere—from your teeth to soil to drain pipes," said Süel. "It's interesting to think that these simple organisms two billion years ago developed the same timesharing strategy that we humans are now using for all kinds of purposes,"

The discovery is the latest advancement from UC San Diego's Center for Microbiome Innovation, which leverages the university's strengths in clinical medicine, bioengineering, computer science, the biological and physical sciences, data sciences and other areas to coordinate and accelerate microbiome research.

More information: "Coupling between distant biofilms and emergence of nutrient time-sharing," Science (2017). science.sciencemag.org/lookup/ … 1126/science.aah4204

Journal information: Science

Provided by University of California - San Diego