Stress may protect—at least in bacteria

Antibiotics harm bacteria and stress them. Trimethoprim (TMP), an antibiotic, inhibits the growth of the bacterium Escherichia coli and induces a stress response. This response also protects the bacterium from subsequent deadly damage from acid. Antibiotics can therefore increase the survival chances of bacteria under certain conditions. This is shown in a study by researchers at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (IST Austria), carried out by Karin Mitosch, Georg Rieckh and Tobias Bollenbach, which was published in the journal Cell Systems.

Bacteria often encounter harsh environmental conditions: pathogens, for example, have to withstand acidity in the stomach. A specific stress response may help them to survive such stressful conditions. At the same time, the response to a specific stress factor may also protect the bacterium from another stress factor; this is known as cross-protection. In their study, first author and PhD student Karin Mitosch and colleagues investigate whether the stress response to antibiotics can also provide such cross-protection.

Antibiotics, i.e. drugs that kill bacteria or inhibit their growth, can also activate stress response genes. So far, it has been unclear whether this stress response may also protect bacteria against other environmental influences. To investigate this question, the researchers exposed the bacterium Escherichia coli to low concentrations of four different antibiotics. At the same time, they measured how transcription changes across the entire genome of the bacterium in response to the antibiotics. Transcription is the copying of DNA into mRNA, which in turn provides the instructions for protein production.

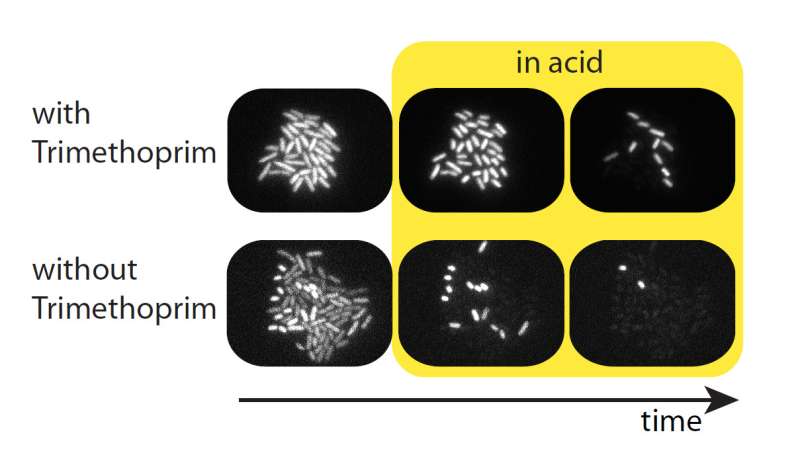

One of the antibiotics investigated, trimethoprim (TMP), induces a rapid acid stress response, which is very variable from one bacterial cell to another. Those bacterial cells with a strong stress response are better protected from a subsequent acid attack. When the researchers exposed bacterial populations to an extremely acidic hydrochloric acid solution, the bacteria died rapidly: their survival is measured as 'half-life' - similar to the decay of radioactive materials -, and amounts to only about 30 minutes. When the researchers placed the bacterial populations into a solution containing low concentrations of TMP first, and only later into the hydrochloric acid solution, the half-life triples to over 100 minutes.

Mitosch and colleagues elucidated the biochemical mechanism on which this cross-protection is based. TMP leads to a depletion of adenine-nucleotides, an important building block of DNA and energy carrier in the cell. This depletion in turn induces the acid stress response. Karin Mitosch explains the importance of their findings: "We propose a way how to find cross-protection between antibiotics and other stress factors. This is important, as our study gives an example for how antibiotics can influence the survival chances of bacteria in different environmental conditions. If we understand which cross-protections exists, targeted strategies may be developed that enhance the effect of antibiotics in the treatment of diseases."

More information: Karin Mitosch et al, Noisy Response to Antibiotic Stress Predicts Subsequent Single-Cell Survival in an Acidic Environment, Cell Systems (2017). DOI: 10.1016/j.cels.2017.03.001

Journal information: Cell Systems

Provided by Institute of Science and Technology Austria