When people know each other, cooperation is more likely than conflict

When anonymity between people is lifted, they more likely cooperate with each other. Playing nice can thereby become a winning strategy, an international team of scientists shows in a study to be published in Science Advances. The findings are based on experiments with a limited number of participants but might have far-reaching implications, if confirmed. Reducing anonymity could help social networks such as Facebook or Twitter that suffer from hate and fake news. It might also help in conflicts about environmental resources.

"Today, it often seems that conflict trumps cooperation, be it on the Internet or in national politics - likewise in evolution, Darwinian selection should result in individuals pursuing their own selfish interest" says lead-author Zhen Wang from Northwestern Polytechnical University in Xi'an, China. Yet despite this perception, there's a lot of cooperation in nature as well as in societies. "Our findings suggest that it is crucial to ask one rather straightforward question: Do the prospective cooperators know each other reasonably well? If they do, they will more likely not try to win at the expense of each other, but together."

Winners play nice - while punishment causes retaliatory sentiments

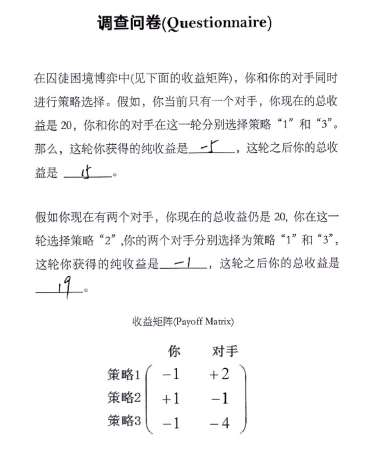

The scientists let 154 undergraduate students at Yunnan University interact pairwise in an experiment originally designed by US mathematicians in the 1950s called the prisoner's dilemma. This is a setup in which two people don't know about each other's actions. They pretend to be on trial. If one testifies against the other, he or she benefits. If both testify, both get high fines. If both do not testify, assuming the same behavior of the other one, they both walk free. The authors modified this basic setup to allow mutual punishment when a pair of non-cooperators meet.

"In our experiments, participants underwent interactions anonymously or onymously, and they faced a threefold choice: to cooperate with one another, to defect from one another, or to punish one another," says co-author Marko Jusup from Hokkaido University, Japan. "We found that when participants knew each other, this significantly increased the frequency of cooperation. This paid out very well for all - so, winners play nice."

The scientists expected that if one participant punishes the other one's antisocial behavior, this would instigate more cooperation. "We've been surprised to see that this was not the case. The punishment seemed to cause retaliatory sentiments, often resulting in further conflict," says Jusup.

Findings might apply to conflicts on Facebook, but also about environmental resources

As with any experimental study, according to the authors there is a danger in extrapolating the results outside the narrow set of controlled conditions. However, it is reassuring that computer simulations built on a small set of straightforward assumptions successfully reproduced the experimental results.

"Since the spirit of cooperation that social cohesion is based upon is crumbling away in some places, be it on Facebook or in societies that are about to be torn apart about issues such as immigration, we sought insight into what enhances cooperation," says co-author Jürgen Kurths from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Germany, who contributed analyses of the statistical significance of the results. "This might also apply to conflicts about environmental resources. However, we have to further explore the continuum, the many states between complete anonymity and very well knowing the other person. It will be exciting to learn what kind of information, what degree of mutual recognition is needed to promote cooperation."

More information: "Onymity promotes cooperation in social dilemma experiments," DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1601444 , advances.sciencemag.org/content/3/3/e1601444

Journal information: Science Advances

Provided by Hokkaido University