According to a study by Utah State University and US Environmental Protection Agency scientists, many land use practices alter the physical and chemical environments of stream ecosystems causing extensive species loss. This image shows a stream draining a reclaimed coal mine. Credit: Ryan Pack, West Virginia Environmental Protection Agency

Scientists from Utah State University and the US Environmental Protection Agency discovered that the frequencies of occurrence of hundreds of insect species inhabiting streams have been altered relative to the conditions that existed prior to wide spread pollution and habitat alteration. Results were similar for the two study regions (the Mid-Atlantic Highlands and North Carolina), where frequencies of occurrence for more than 70 percent of species have shifted. In both regions, nearly all historically common species were found in fewer streams and rivers than expected. The study was recently published in Freshwater Science. The authors of the study are Charles (Chuck) Hawkins of Utah State University and Lester Yuan of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The lead author (Hawkins) commented: "Scientists have known for decades that many freshwater species are sensitive to human-caused pollution and habitat destruction. However, most previous studies of the regional status of different species have focused on relatively large vertebrates." Hawkins said we know much less about the status of insects and other aquatic invertebrates that inhabit freshwaters. These species tend to be small and inconspicuous and therefore out of the public eye, but they can be as important as their larger counterparts. For example, aquatic insects provide food to fish, and they also help maintain high water quality by consuming both algae and decaying organic matter as well as filtering particulate matter out of the water."

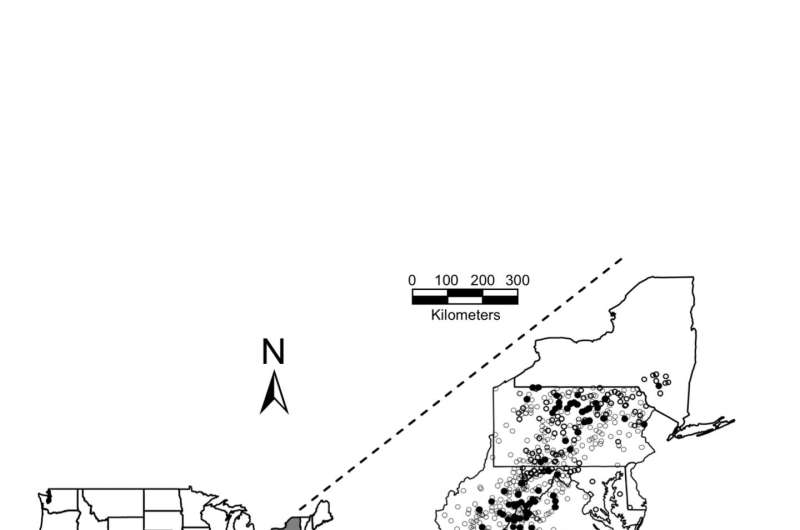

Hawkins said the biggest technical challenge in conducting their study was to determine what specific species likely occurred in each of the many different types of streams and rivers prior to the effects of pollution and habitat alteration. "Ideally we would compare current collection records with data collected prior to pollution at each stream, but such historical information does not exist for the vast majority of streams and rivers." He said, "Imagine having to reconstruct a complex painting when over 90% of the painting has been altered or destroyed and then use that reconstruction to estimate what elements of the original painting have been altered the most." The authors solved this problem by using data collected at different types of unpolluted, 'reference' rivers and streams in each region to predict what specific species should have occurred in all other streams. "We then compared the species observed in each of several hundred study streams with the ones predicted to occur in each of those streams under pre-polluted conditions."

Scientists from Utah State University and the US Environmental Protection Agency have shown that the frequencies of occurrence of hundreds of freshwater insect species have changed relative to historical conditions. Credit: Utah State University

Hawkins said "It's important to conduct these types of studies, because these and other species are the 'natural capital' that creates the ecosystem products and services that human societies depend on. We need to manage that capital better than we have in the past. Hawkins stated that the approach the authors used in this study can be applied to other regions to provide critically important information on the status of the thousands of freshwater species that occur around the world.

According to a study conducted by scientists from Utah State University and the US Environmental Protection Agency, the mayfly Epeorus pleuralis, one of the many hundreds of species of stream insects whose frequencies of occurrence has declined relative to historical conditions. Credit: David Funk, Stroud Water Resources Center, Pennsylvania

More information: Charles P. Hawkins et al, Multitaxon distribution models reveal severe alteration in the regional biodiversity of freshwater invertebrates, Freshwater Science (2016). DOI: 10.1086/688848

Provided by Utah State University