Researchers create new way to trap dangerous gases

A team of researchers at The University of Texas at Dallas has developed a novel method for trapping potentially harmful gases within microscopic organo-metallic structures.

These metal organic frameworks, or MOFs, are made of different building blocks composed of metal ion centers and organic linker molecules. Together they form a honeycomb-like structure that can trap gases within each comb, or pore.

The tiny nano-scale structures also have the potential to trap various emissions from things as immense as coal factories and as small as cars and trucks. However, there are some molecules that are simply too weakly adsorbed to remain contained within the MOF scaffolding. Adsorption describes how an extremely thin layer of molecules (as of gases, solutes or liquids) can cling to the surfaces of solid bodies or liquids.

"These structures have the ability to store gases, but some gases are too weakly bound and cannot be trapped for any substantial length of time," said Dr. Kui Tan, a research scientist in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering at UT Dallas and lead author of the study published online Dec. 13 in Nature Communications.

After studying this problem, Tan decided to try to introduce a molecule that can cap the outer surface of each MOF crystal in the same way bees seal their honeycombs with wax to keep the honey from spilling out.

In this case, Tan introduced vapors of a molecule called ethylenediamine, or EDA, that created a monolayer, effectively sealing the MOF "honeycomb" and trapping gases such as carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide and nitric oxide within.

This monolayer is less than 1 nanometer in thickness, or less than half the size of a single strand of DNA.

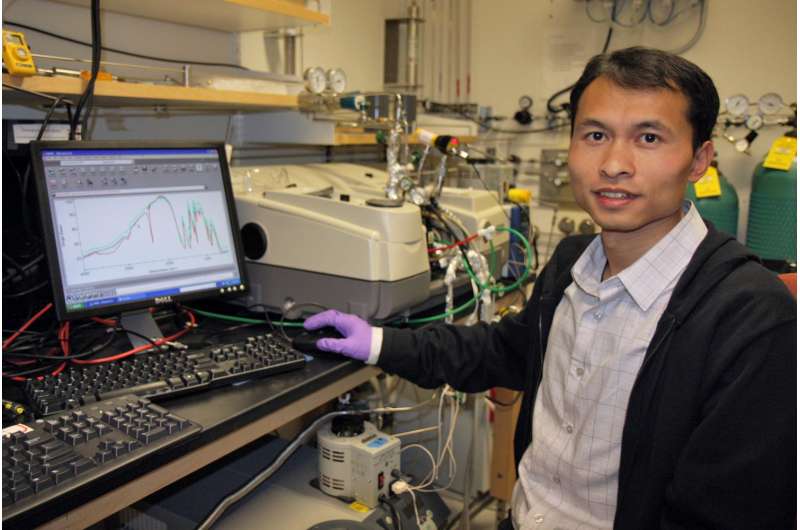

To quantify how much gas was trapped and remained in the EDA-capped MOF structures, Tan and his team used time-resolved, in-situ infrared spectroscopy, testing the efficiency of this molecular "cork" to trap weakly adsorbed gases.

The presence of the gas molecules adsorbed in the MOF was displayed on a nearby computer screen as inverted peaks, which revealed that EDA vapor was able to effectively retain the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide for up to a day.

"Potential applications of this finding could include storage and release of hydrogen or natural gas to run your car, or in industrial uses where the frameworks could trap and separate dangerous gases to keep them from entering the atmosphere," Tan said.

As an added discovery, Tan found that a mild exposure to water vapor would disrupt the monolayer, penetrate the framework and fully release the entrapped vapors at room temperature. Such selectivity of the EDA membrane opens up new options for managing gas emissions, he said.

"The idea of using EDA as a cap came from Kui who proceeded to do an enormous amount of work to demonstrate this new concept, with critical theoretical input from our collaborators at Wake Forest University," said Dr. Yves Chabal, head of the materials science and engineering department in the Erik Jonsson School of Engineering and Computer Science and senior author of the paper.

More information: Kui Tan et al, Trapping gases in metal-organic frameworks with a selective surface molecular barrier layer, Nature Communications (2016). DOI: 10.1038/ncomms13871

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by University of Texas at Dallas