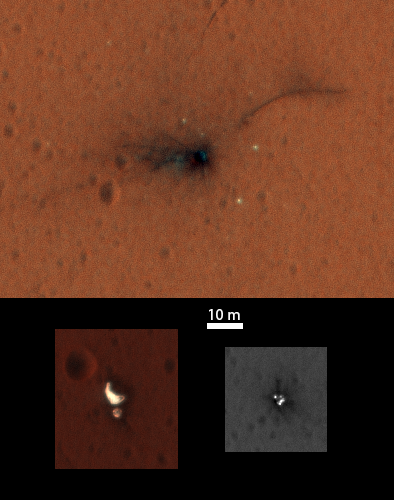

Composite of the ExoMars Schiaparelli module elements seen by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) on 1 November 2016. Both the main impact site (top) and the region with the parachute and rear heatshield (bottom left) are now captured in the central portion of the HiRISE imaging swath that is imaged through three different filters, enabling a colour image to be constructed. The front heatshield (bottom right) lies outside the central colour imaging swath. The colours have been graded according to the specific region to best reveal the contrast of features against the martian background. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

New high-resolution images taken by a NASA orbiter show parts of the ExoMars Schiaparelli module and its landing site in colour on the Red Planet.

Schiaparelli arrived in the Meridiani Planum region on Mars on 19 October, while its mothership began orbiting the planet. The Trace Gas orbiter will make its first science observations during two of its highly elliptical circuits around Mars – corresponding to eight days – starting on 20 November, including taking its first images of the planet since arriving.

The new image of Schiaparelli and its hardware components was taken by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, or MRO, on 1 November. The main impact site is now captured in the central portion of the swath that is imaged by the high-resolution camera through three filters, enabling a colour image to be constructed.

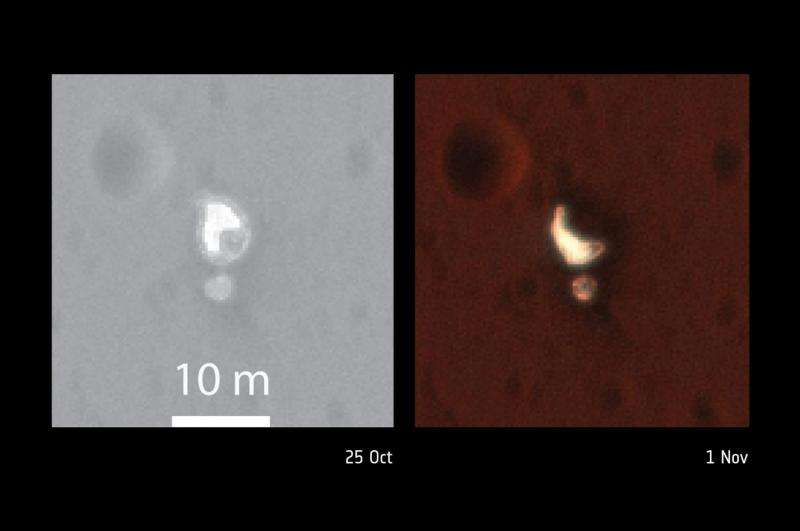

In addition, the image of 1 November was taken looking slightly to the west, while the earlier image was looking to the east, providing a contrasting viewing geometry.

Indeed, the latest image set sheds new light on some of the details that could only be speculated from the first look last week.

For example, a number of the bright white spots around the dark region interpreted as the impact site are confirmed as real objects – they are not likely to be imaging 'noise' – and therefore are most likely fragments of Schiaparelli.

Interestingly, a bright feature can just be made out in the place where the dark crater was identified in last week's image. This may be associated with the module, but the images so far are not conclusive.

A comparison of the 25 October image taken by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter HiRISE camera with that taken on 1 November. In the week that elapsed, the outline of Schiaparelli’s parachute on the martian surface has apparently changed, which is interpreted as movement due to local wind. The parachute has a maximum diameter of 12 m, and it is attached to the rear heatshield, which measures about 2.4 m across. Aside from the obvious difference of the 1 November being in colour, the images have slightly different projections: in the colour image north is about 7º west of straight up. In addition, the 25 October image was looking to the east, while the 1 November image was taken looking slightly to the west. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

A bright fuzzy patch revealed in the colour image alongside the dark streaks to the west of the crater could be surface material disturbed in the impact or from a subsequent explosion or explosive decompression of the module's fuel tanks, for example.

About 0.9 km to the south, the parachute and rear heatshield have also now been imaged in colour. In the time that has elapsed since the last image was taken on 25 October, the outline of the parachute has changed. The most logical explanation is that it has been shifted in the wind, in this case slightly to the west. This phenomenon was also observed by MRO in images of the parachute used by NASA's Curiosity rover.

A stereo reconstruction of this image in the future will also help to confirm the orientation of the rear heatshield. The pattern of bright and dark patches suggest it is sitting such that we see the outside of the heatshield and the signature of the way in which the external layer of insulation has burned away in some parts and not others – as expected.

Finally, the front heatshield has been imaged again in black and white – its location falls outside of the colour region imaged by MRO – and shows no changes. Because of the different viewing geometry between the two image sets, this confirms that the bright spots are not specular reflections, and must therefore be related to the intrinsic brightness of the object. That is, it is most likely the bright multilayer thermal insulation that covers the inside of the front heatshield, as suggested last week.

Further imaging is planned in about two weeks, and it will be interesting to see if any further changes are noticed.

The images may provide more pieces of the puzzle as to what happened to Schiaparelli as it approached the martian surface.

Following its successful atmospheric entry and subsequent slowing due to heatshield and parachute deceleration, the internal investigation into the root cause of the problems encountered by Schiaparelli in the latter stages of its six-minute descent continues. An independent inquiry board has been initiated.

Provided by European Space Agency