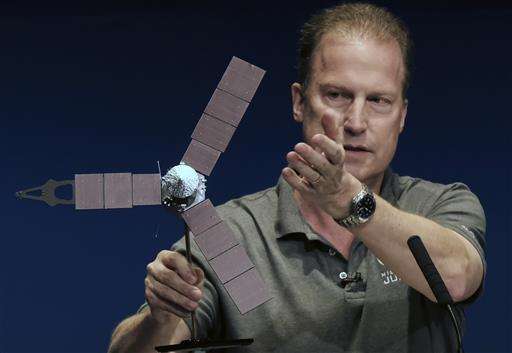

Scott Bolton speaks in a post-orbit insertion briefing at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory following the solar-powered Juno spacecraft entered orbit around Jupiter on Monday, July 4, 2016, in Pasadena, Calif. (AP Photo/Ringo H.W. Chiu)

Soaring over Jupiter's poles, a NASA spacecraft arrived at the solar system's largest planet on a mission to peek behind the cloud tops.

The final leg of the five-year voyage ended Monday when the solar-powered Juno spacecraft fired its main rocket engine and gracefully slipped into orbit around Jupiter. Mission controllers celebrated when Juno sent back radio signals confirming it reached its destination.

"We're there. We're in orbit. We conquered Jupiter," Juno chief scientist Scott Bolton said during a post-mission briefing.

In the weeks leading up to the encounter, Juno snapped pictures of the giant planet and its four inner moons dancing around it. Scientists were surprised to see Jupiter's second-largest moon, Callisto, appearing dimmer than expected.

The spacecraft's camera and other instruments were switched off for arrival, so there weren't any pictures at that key moment. Scientists have promised close-up views of the planet when Juno skims the cloud tops during the 20-month, $1.1 billion mission managed by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The fifth rock from the sun and the heftiest planet in the solar system, Jupiter is what's known as a gas giant—a ball of hydrogen and helium—unlike rocky Earth and Mars.

This artist's rendering provided by NASA and JPL-Caltech shows the Juno spacecraft above the planet Jupiter. Five years after its launch from Earth, Juno is scheduled to go into orbit around the gas giant on Monday, July 4, 2016. (NASA/JPL-Caltech via AP)

With its billowy clouds and colorful stripes, Jupiter is an extreme world that likely formed first, shortly after the sun. Unlocking its history may hold clues to understanding how Earth and the rest of the solar system developed.

Named after Jupiter's cloud-piercing wife in Roman mythology, Juno is only the second mission designed to spend time at Jupiter.

Galileo, launched in 1989, circled Jupiter for nearly a decade, beaming back splendid views of the planet and its numerous moons. It uncovered signs of an ocean beneath the icy surface of the moon Europa, considered a top target in the search for life outside Earth.

Juno's mission: To peer through Jupiter's cloud-socked atmosphere and map the interior from a unique vantage point above the poles. Among the lingering questions: How much water exists? Is there a solid core? Why are Jupiter's southern and northern lights the brightest in the solar system?

In this photo provided by NASA, Juno team members celebrate in mission control of the Space Flight Operations Facility at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory after they received confirmation from the spacecraft that it has successfully entered orbit of Jupiter, Monday, July 4, 2016, in Pasadena, Calif. The Juno mission launched August 5, 2011, and will orbit the planet for 20 months to collect data on the planetary core, map the magnetic field, and measure the amount of water and ammonia in the atmosphere. (Aubrey Gemignani/NASA via AP)

"What Juno's about is looking beneath that surface," said Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in Texas. "We've got to go down and look at what's inside, see how it's built, how deep these features go, learn about its real secrets."

There's also the mystery of its Great Red Spot. Recent observations by the Hubble Space Telescope revealed the centuries-old monster storm in Jupiter's atmosphere is shrinking.

The trek to Jupiter, spanning nearly five years and 1.8 billion miles (2.8 billion kilometers), took Juno on a tour of the inner solar system followed by a swing past Earth that catapulted it beyond the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Along the way, Juno became the first spacecraft to cruise that far out powered by the sun, beating Europe's comet-chasing Rosetta spacecraft. A trio of massive solar wings sticks out from Juno like blades from a windmill, generating 500 watts of power to run its nine instruments.

Scott Bolton, left, and Rick Nybakken are seen in a post-orbit insertion briefing at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory following the solar-powered Juno spacecraft entered orbit around Jupiter on Monday, July 4, 2016, in Pasadena, Calif. (AP Photo/Ringo H.W. Chiu)

In the coming days, Juno will turn its instruments back on, but the real work won't begin until late August when the spacecraft swings in closer. Plans called for Juno to swoop within 3,000 miles (5,000 kilometers) of Jupiter's clouds—closer than previous missions—to map the planet's gravity and magnetic fields in order to learn about the interior makeup.

Juno braved a hostile radiation environment to reach Jupiter. Engineers prepared by housing the spacecraft's computer and electronics in a titanium vault. Even so, Juno is expected to get blasted with radiation equal to more than 100 million dental X-rays during the mission.

Like Galileo before it, Juno meets its demise in 2018 when it deliberately dives into Jupiter's atmosphere and disintegrates—a necessary sacrifice to prevent any chance of accidentally crashing into the planet's potentially habitable moons.

-

From left to right, Goeff Yoder, Diane Brown, Scott Bolton, Rick Nybakken, Guy Beutelschies, and Steve Levin participate in a post-orbit insertion briefing at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory following the solar-powered Juno spacecraft entered orbit around Jupiter on Monday, July 4, 2016 in Pasadena, Calif. (AP Photo/Ringo H.W. Chiu)

-

Marla Thornton, left, celebrates with Steve Levin in Mission Control at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory as the solar-powered Juno spacecraft goes into orbit around Jupiter on Monday, July 4, 2016, in Pasadena, Calif. (AP Photo/Ringo H.W. Chiu, Pool)

-

Heidi Becker, right, Juno radiation monitoring investigation lead, discusses the challenges of radiation the Juno spacecraft will encounter as Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager, left, looks on during a briefing at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif. on Monday, July 4, 2016. The solar-powered spacecraft is on it's way toward Jupiter for the closest encounter with the biggest planet in our solar system. NASA's Juno spacecraft will fire its main rocket engine late Monday to slow itself down from a speed of 150,000 mph (250,000 kph) and slip into orbit around Jupiter. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

-

Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager, holds a model of the Juno spacecraft while talking about the solar panels and the orbit it will take around Jupiter during a briefing at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., on Monday, July 4, 2016. The solar-powered spacecraft is on it's way toward Jupiter for the closest encounter with the biggest planet in our solar system. NASA's Juno spacecraft will fire its main rocket engine late Monday to slow itself down from a speed of 150,000 mph (250,000 kph) and slip into orbit around Jupiter. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

-

Data Controller Nick Lam, monitors the Juno spacecraft inside Mission Control in the Space Flight Operations Facility at Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in Pasadena, Calif., Monday, July 4, 2016. NASA's Juno spacecraft will fire its main rocket engine late Monday to slow itself down from a speed of 150,000 mph (250,000 kph) and slip into orbit around Jupiter. The solar-powered spacecraft is spinning toward Jupiter for the closest encounter with the biggest planet in our solar system. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

-

Journalists work in preparation for NASA's Juno spacecraft's orbit around Jupiter in the media center at Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in Pasadena, Calif., Monday, July 4, 2016. The spacecraft will fire its main rocket engine late Monday to slow itself down from a speed of 150,000 mph (250,000 kph) and slip into orbit around Jupiter. The solar-powered spacecraft is spinning toward Jupiter for the closest encounter with the biggest planet in our solar system. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

More information: Mission page: tinyurl.com/Jupitermission

© 2016 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.