Scientists battle to save world's coral reefs

After the most powerful El Nino on record heated the world's oceans to never-before-seen levels, huge swaths of once vibrant coral reefs that were teeming with life are now stark white ghost towns disintegrating into the sea.

And the world's top marine scientists are still struggling in the face of global warming and decades of devastating reef destruction to find the political and financial wherewithal to tackle the loss of these globally important ecosystems.

"What we have to do is to really translate the urgency," said Ruth Gates, president of the International Society for Reef Studies and director of the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology.

Gates, who helped organize a conference this week for more than 2,000 international reef scientists, policymakers and others, said the scientific community needs to make it clear how "intimately reef health is intertwined with human health."

The International Coral Reef Symposium convenes Monday to try to create a more unified conservation plan for coral reefs. She said researchers have to find a way to implement large scale solutions with the help of governments.

Consecutive years of coral bleaching have led to some of the most widespread mortality of reefs on record, leaving scientists in a race to save them. While bleached coral often recovers, multiple years weakens the organisms and increases the risk of death.

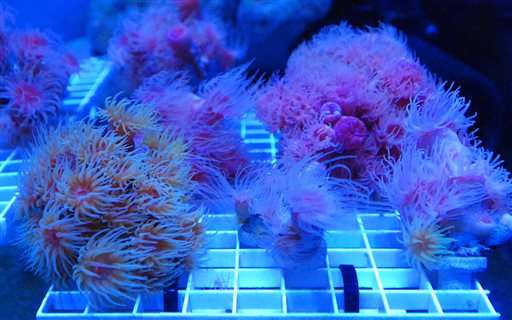

Researchers have achieved some success with projects such as creating coral nurseries and growing forms of "super coral" that can withstand harsher conditions. But much of that science is being done on a very small scale with limited funding.

Bob Richmond, director of the University of Hawaii's Kewalo Marine Laboratory, said the problems are very clear: "overfishing of reef herbivores and top predators, land-based sources of pollution and sedimentation, and the continued and growing impacts of climate change."

While reefs are major contributors to many coastal tourist economies, saving the world's coral isn't just about having pretty places for vacationers to explore. Reefs are integral to the overall ecosystem and are an essential component of everyday human existence.

Reefs not only provide habitat for most ocean fish consumed by humans, but they also shelter land from storm surges and rising sea levels. Coral has even been found to have medicinal properties.

In one project to help save reefs, researchers at the University of Hawaii's Institute of Marine Biology have been taking samples from corals that have shown tolerance for harsher conditions in Oahu's Kaneohe Bay and breeding them with other strong strains in slightly warmer than normal conditions to create a super coral.

The idea is to make the corals more resilient by training them to adapt to tougher conditions before transplanting them into the ocean.

Another program run by the state of Hawaii has created seed banks and a fast-growing coral nursery for expediting coral restoration projects.

Most of Hawaii's species of coral are unlike other corals around the world in that they grow very slowly, which makes reef rebuilding in the state difficult. So officials came up with a plan to grow large chunks of coral in a fraction of the time it would normally take.

Coral reefs have almost always been studied up close, by scientists in the water looking at small portions of reefs.

But NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory is taking a wider view, from about 23,000 feet above. NASA and other scientists recently launched a three-year campaign to gather new data on coral reefs worldwide. They are using specially designed imaging instruments attached to aircraft.

"The idea is to get a new perspective on coral reefs from above, to study them at a larger scale than we have been able to before, and then relate reef condition to the environment," said Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences' Eric Hochberg, principal investigator for the project.

If the scientific community and the world's governments can't come together to address coral's decline, one of earth's most critical habitats could soon be gone, leaving humans to deal with the unforeseen consequences.

"What happens if we don't take care of our reefs?" asked Gates. "It's dire."

© 2016 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.