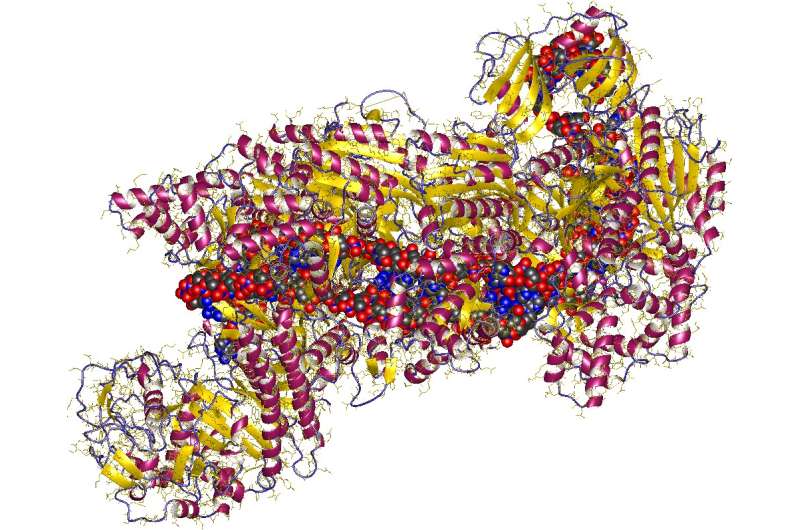

CRISPR (= Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) + DNA fragment, E.Coli. Credit: Mulepati, S., Bailey, S.; Astrojan/Wikipedia/ CC BY 3.0

(Phys.org)—A small team of researchers at Harvard University has taken another look at CRISPR and has found that it can be used as a recording device of sorts, keeping track of when and where a given bacterium has been exposed to different viruses. In their paper published in the journal Science, the team describes their study, their findings and the ways such natural recordings might be useful.

CRISPR has been in the news a lot of late, primarily due to its use in gene editing—but lost in all the news is the actual basis of the technology. Like humans, bacteria have a unique immune system, which is known as CRISPR/Cas, and it works by cutting out pieces of DNA (called oligomers) when attacking viruses and integrating those pieces into its own genome, which is later used to give the bacterium historical knowledge when fighting the virus should it appear again. The researchers with this new effort noted that the oligomers that are placed in the genome are done so sequentially, which means they form a record of viral attacks. To see its history, the team reasoned, the genome need only be sequenced.

To test this idea, the researchers used a simplified version of E. coli, which still contained Cas1 and Cas2, the enzymes needed for snipping and adding oligomers, but no other immune system functionality. They then directly exposed it to various DNA sequences over a period of time, allowed it to snip and add to its genome, then sequenced the bacterium to see if the theory held up. The team reports that it did indeed. Taking the idea further they found that by introducing modified versions of Cas 1 and Cas2 that they could actually create different recording modes.

The team suggests this new bit of knowledge regarding CRISPR might be used to aid in creating bacteria that could be used as sensors of a sort, offering recording evidence of a host of different microorganisms in a given environment. Such sensors could prove useful in applications ranging from soil testing, to human gut biome analysis to atmospheric probes.

Journal information: Science

© 2016 Phys.org