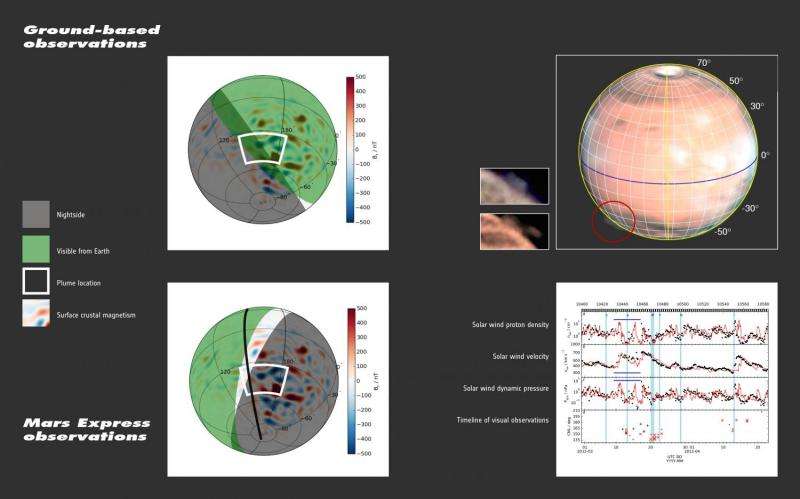

Examples of Earth-based observations of the mysterious plume seen on 21 March 2012 (top right) and of Mars Express solar wind observations during March and April 2012 (bottom right). The left-hand graphics depict the region visible from Earth at the time (green), the nightside of Mars (grey) and the surface crustal magnetism (background colours and scale). The white box indicates the area in which the plume observations were made. Together these graphics show that the Earth-based observations were made during the martian daytime, along the dawn terminator, while the spacecraft observations were made along the dusk terminator, approximately half a martian ‘day’ later. On the lower graphic a ground track of Mars Express is shown during a data collection period on 20 March. The plot on the lower right shows various properties measured by Mars Express, including solar wind proton density (top), velocity (second row) and dynamic pressure (third row). The peaks marked by the horizontal blue line indicate the increase in the solar wind properties as a result of the impact of the coronal mass ejection. The bottom row of the graph shows the timeline of ground-based observations. Positive detections are marked in red, non-detections are marked in black (the size of the symbol indicates the assessed quality of the observation). Credit: D. Parker (large Mars image and bottom inset) & W. Jaeschke (top inset). All other graphics courtesy D. Andrews

Mysterious high-rise clouds seen appearing suddenly in the martian atmosphere on a handful of occasions may be linked to space weather, say Mars Express scientists.

Amateur astronomers using telescopes on Earth were the first to report an unusual cloud-like plume in 2012 that topped-out high above the surface of Mars at an altitude around 250 km. The feature developed in less than 10 hours, covered an area of up to 1000 x 500 km, and remained visible for around 10 days.

The extreme altitude poses something of a problem in explaining the features: it is far higher than where typical clouds of frozen carbon dioxide and water are thought to be able to form in the atmosphere.

Indeed, the high altitude corresponds to the ionosphere, where the atmosphere directly interacts with the incoming solar wind of electrically charged atomic particles.

Speculation as to their cause has included exceptional atmospheric circumstances, auroral emissions, associations with local crustal anomalies, or a meteor impact, but so far it has not been possible to identify the root cause.

Unfortunately, the spacecraft orbiting Mars were not in the right position to see the 2012 plume visually, but scientists have now looked into plasma and solar wind measurements collected by Mars Express at the time.

They have found evidence for a large 'coronal mass ejection', or CME, from the Sun striking the martian atmosphere in the right place and at around the right time.

"Our plasma observations tell us that there was a space weather event large enough to impact Mars and increase the escape of plasma from the planet's atmosphere," says David Andrews of the Swedish Institute of Space Physics, and lead author of the paper reporting the Mars Express results.

"But we were not able to see any signatures in the ionosphere that we can categorically say were due to the presence of this plume.

"One problem is that the plume was seen at the day–night boundary, over a region of known strong crustal magnetic fields where we know the ionosphere is generally very disturbed, so searching for 'extra' signatures is rather challenging."

Observations of a mysterious plume-like feature (marked with yellow arrow) at the limb of the Red Planet on 20 March 2012. The observation was made by astronomer W. Jaeschke. The image is shown with the north pole towards the bottom and the south pole to the top. Credit: W. Jaeschke

To go further, the scientists have looked at the chances of these two relatively rare events – a large and fast CME colliding with Mars, and the mysterious plume – occurring at the same time.

They have been searching back through the archives for similar events, but they are rare.

For example, the Hubble Space Telescope observed a similar high plume in May 1997, and a CME was registered hitting Earth at the same time.

Although that CME was widely studied, there is no information from Mars orbiters to judge the scale of its impact at the Red Planet.

Similarly, CMEs have been detected at Mars without any associated plume being reported, although changes in distance and visibility of Mars from Earth makes it difficult to acquire good ground-based images at all times.

"The jury is still out as to what physics is at play here, but given the altitude of the plume, we think that plasma interactions must be important," says David.

"One idea is that a fast-travelling CME causes a significant perturbation in the ionosphere resulting in dust and ice grains residing at high altitudes in the upper atmosphere being pushed around by the ionospheric plasma and magnetic fields, and then lofted to even higher altitudes by electrical charging.

"This could lead to a plume effect that is significant enough to be detected from Earth by astronomers."

"A number of processes could be responsible, but if these plumes are indeed driven by space-weather disturbances, this adds an important angle to our understanding of how Mars may have lost much of its atmosphere in the past, changing from a warm, wet world and becoming the cold, dry, dusty place it is today," says Dmitri Titov, Mars Express project scientist.

"The plume also emphasises the scientific potential for continuous monitoring of Mars by both orbiters and ground-based observatories. In particular, we are now going to use the webcam on Mars Express for more frequent coverage of the planet."

Provided by European Space Agency