Philae, the little lander that was declared lost by the European Space Agency (ESA), has achieved a lot despite its relatively short operational life on the surface of the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Future comet landing missions could be built upon the legacy that this small, wayward probe leaves behind.

The box-shaped lander was a part of ESA's Rosetta mission, launched on Mar. 2, 2004. Philae accomplished its spectacular comet landing on Nov. 12, 2014, but went silent three days later. The lander made contact on June 13, 2015 and sent its 'health' data. According to ESA, the lander established contact with the ground team seven more times, but these contacts were erratic and unpredictable. The probe has remained silent since July 9, 2015 and the probability of re-establishing contact with Philae is currently almost zero.

The spacecraft is probably covered with dust in its shaded location, not receiving enough sunlight to start warming up to operational status. Thus, it is in a state of permanent hibernation. There were hopes that Philae would wake up again when the comet moved closer to the sun ahead of perihelion on Aug. 13, 2015. However, even with the improved thermal conditions, no further contacts were made.

"Unfortunately, chances to re-establish contact are very low. We are getting too far from the sun again," Stephan Ulamec, Philae project manager at the German Aerospace Center (DLR), told Astrowatch.net.

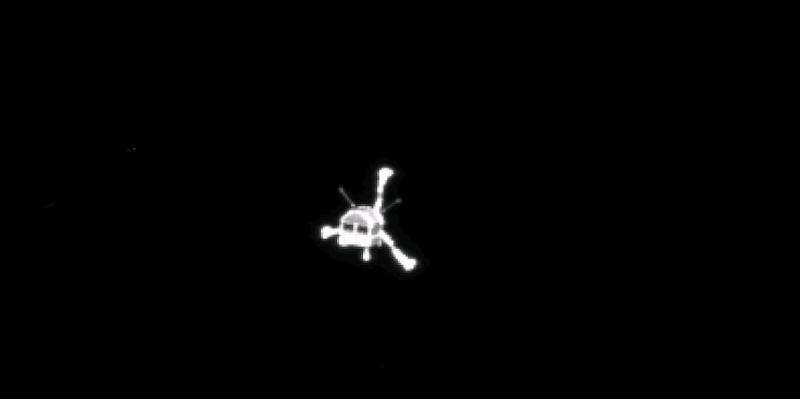

The last images of Philae will probably be acquired later this year, when the Rosetta orbiter will image the lander during close fly-bys.

"Rosetta is operational till September, and we hope to receive informative images of the lander from the orbiter camera," Ulamec said.

Despite its short life on the comet, Philae accomplished much, and is leaving a rich legacy of data that could come in handy during future to small icy bodies.

The little probe was the first to land on a comet's surface and carry out measurements there. The lander conducted over 60 hours of research with its instruments, acquired images, was able to sense molecules and tried to hammer the unexpectedly hard cometary surface.

"Philae was able to conduct the first-ever measurements from the surface of a comet. Some of the results include the indication that the comet surface is non-magnetic; high-resolution camera images from the surface material; analyses and the detection of rich organic chemistry; measurements of the physical properties of the surface material and measurements of the internal structure by radar sounding," Ulamec said.

The scientists studying the results provided by Philae agree that its measurements offer a unique insight into the composition and, in particular, the water content and porosity of the comet mantle. The researchers were also able to map out the global dust transport on the surface of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

Even Philae's landing event delivered crucial information that could be useful for similar endeavors in the future. The spacecraft failed to fire its harpoons and lock itself onto the surface of the comet after its descent, bouncing from its initial touchdown point. It made contact with the comet four times during its additional flight across the small comet lobe.

"We learned that the cometary surface, at least where Philae landed, was quite hard, and, thus, bouncing is more of a problem than, e.g., sinking into the surface dust. Having a redundant system and for example, a large primary battery, has proven to be the right strategy," Ulamec said.

Philae sets the path for similar comet exploration missions. However, Ulamec admitted that much more could be achieved by sample-return probes.

"The concept of Philae was good. Future missions will make use of newer technologies, allowing, for example, improved miniaturization of instruments or more powerful computers. The next big step in cometary science may become sample return. There is no way to perform in-situ analyses as sophisticated as in laboratories on Earth," he concluded.

Provided by Astrowatch.net