Study finds human trafficking is judged unevenly by law, public

The severity of the criminal penalty for human trafficking in the U.S. has no effect on the number of suspects who are arrested and prosecuted for the crime, according to a wide-ranging new study by Northeastern criminologist Amy Farrell and her research partners.

The study also found that few states have developed the expertise to consistently charge human traffickers and that certain sex-related behaviors impact beliefs about what has now become known as modern-day slavery.

The findings were published Monday by the National Institute of Justice, which funded the research with a three-year, $500,000 grant. The study—titled "Identifying Effective Counter-Trafficking Programs and Practices in the U.S.: Legislative, Legal, and Public Opinion Strategies that Work"—represents the first-ever report on the efficacy of the nation's anti-human trafficking efforts, and its release coincides with Human Trafficking Awareness Month.

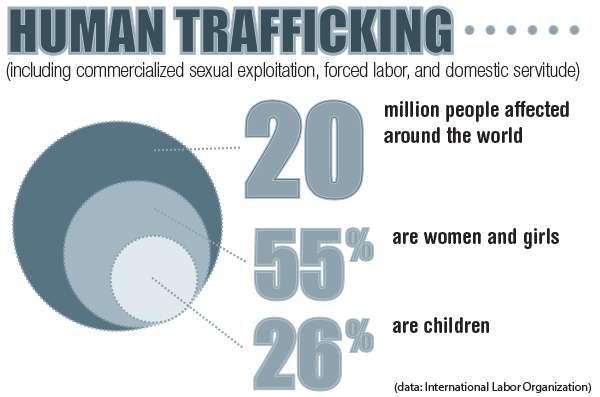

According to the International Labor Organization, human trafficking, which includes commercialized sexual exploitation, forced labor, and domestic servitude, denies freedom to some 20 million people around the world. Fifty-five percent are women and girls. Twenty-six percent are children. The Polaris Project, a nongovernmental organization that works to combat modern-day slavery and human trafficking, estimates that the total number of human trafficking victims in the U.S. alone reaches into the hundreds of thousands.

In their report, the researchers looked at what legislative, legal, and civic responses have led to the most human trafficking arrests and prosecutions with an eye toward bringing their conclusions to legislators, policymakers, and anti-trafficking agencies. As they wrote in the report, "criminalization of trafficking perpetrators and the activation of support for trafficking victims through the criminal justice process has been one of the primary responses to concern about human trafficking in the U.S."

More comprehensive laws, not harsher criminal penalties, lead to more arrests and prosecutions

Farrell, associate professor of criminology who studies how the criminal justice system responds to human trafficking, and her research colleagues from Colorado College and Texas Christian University broke up the report into three parts: evaluating how state anti-trafficking statues impact human trafficking arrests and prosecutions; analyzing state human trafficking cases; and assessing public opinion on human trafficking.

In part one, they worked to determine whether state adoption of various anti-trafficking laws increased the identification, arrest, and prosecution of human trafficking suspects. First the researchers classified all state human trafficking laws enacted between 2003 and 2012 into three broad categories: criminalization, state investment, and civil remedies. Then they utilized mathematical models to predict whether the statutory provisions within each of these categories were associated with the arrest and prosecution of human trafficking offenders in each state in the years following enactment.

What they found, in analyzing the human trafficking arrest and prosecution outcomes of 3,225 suspects identified in open source information across all states from 2003 to 2012, is that comprehensive laws that invested in fiscal and human resources increased arrests and prosecutions for human trafficking. But what was more surprising is that harsher criminal penalties did not.

"These results suggest that, while harsher criminal sentences may be an 'easy sell' for state legislators, it does not produce law enforcement outcomes," said Vanessa Bouché, Farrell's co-author from TCU. "Instead, when legislatures put state resources behind combatting human trafficking, it signals to law enforcement that this is a state priority."

To wit, the researchers found that nearly every aspect of state investment in human trafficking—from training law enforcement to forming a task force—had a significant impact on increasing state arrests for the crime. As it turned out, the most important provision to increasing arrests is requiring the National Human Trafficking Hotline number to be posted in public places.

Unlike state investment, the use of civil provisions—including restitution and low burden of proof—did not effectively predict arrests and prosecutions. But there were two exceptions, provisions whose employment seemed to increase both: One was safe harbor, which refers to state laws that provide immunity to minor victims of human trafficking for certain offenses they were forced to commit while being trafficked. The other was civil action, which refers to a legal action to compel a civil remedy, such as the ability to seek compensatory or punitive damages.

As Farrell and her colleagues put it in the report: "The research suggests that in the absence of strong state investment, safe harbor, and civil actions provisions, a state's human trafficking enforcement will be lacking."

Among other part-one findings:

- The number of states criminalizing human trafficking steadily increased from 2003 to 2012; by 2012, every state but Wyoming had criminalized human trafficking through the creation of a stand-alone human trafficking crime or by integrating human trafficking into an existing criminal offense.

- By 2012, a dozen states still had not made any state investment in human trafficking, and only Ohio, Texas, and Minnesota had made investments in all six categories: assisting victims, forming a task force, training law enforcement, reporting on human trafficking, posting the human trafficking hotline number, and utilizing investigative tools, like the ability to wiretap.

Few states have developed expertise in charging offenders

In part two of their study, the researchers utilized data on more than 470 suspects who were prosecuted under a state human trafficking statute from 2003 to 2012 in order to analyze the characteristics of human trafficking offenses adjudicated in state courts.

In particular, they were looking to determine the distribution of different types of human trafficking charges; the demographics of human trafficking suspects; and the types of additional charges for those charged with human trafficking.

They found that only a few states had developed expertise in charging offenders. One state alone—California—charged 39 percent of all the suspects in the sample.

"Although all states have laws that allow the prosecution of human trafficking, suspects are not evenly prosecuted across the country," Farrell explained. "Rather, there are pockets of prosecutions, suggesting that only a small group of states has figured out how to charge offenders."

As the researchers wrote in the report, "The number of state human trafficking convictions is likely to remain low until more state human trafficking charges are pursued through trial and a legal culture develops that supports upholding these convictions."

Among other part-two findings:

- Approximately 79 percent of those prosecuted for state human trafficking crimes were male and 21 percent were female. Their average age was 32.

- On average, suspects were charged with five state offenses, including human trafficking. The most common accompanying charges were prostitution, pimping, sexual abuse or rape, and kidnapping.

- Offenders convicted of any state crime were sentenced to an average of 99 months in state prison. Those convicted of at least one human trafficking charge were sentenced to an average of 115 months in prison.

- Suspects charged with general human trafficking faced longer sentences when their cases went to trial than when they were adjudicated through plea. On average, suspects faced 65-month sentences if convicted following a guilty plea and 215-month sentences if convicted following a trial.

The majority of the public knows that human trafficking is a form of slavery

In part three of their study, the researchers analyzed the results of their survey of a representative sample of 2,000 Americans. Their goal was to find out what the public knows, thinks, and feels about human trafficking.

They found that 90 percent of the public understands that human trafficking is a form of slavery, but that many hold incorrect beliefs about the global scourge. More than 90 percent believe that human trafficking victims are almost always female, for example, while 62 percent believe that it involves mostly illegal immigrants.

Respondents were moved most by victims who were minors, but they showed more concern and wanted to see more government involvement when it came to the human trafficking of boys. Respondents who consumed pornography or visited a strip club thought human trafficking should be less of a government priority, regardless of their level of knowledge of the crime.

"Human trafficking feels overwhelming to people, but the level of concern among people is not equal," Farrell explained. "On the whole, they think it's a terrible thing, but they don't know how to fix it and think it should be someone else's problem."

Among other part-three findings:

- More than 80 percent of the public reported that they had "some" or "a lot" of concern about human trafficking.

- Democrats, older Americans, and racial minorities were the most concerned about human trafficking and thought it should be a higher government priority. White males were the least concerned.

- Almost 50 percent said human trafficking should be a top government priority; the highest levels of support for programs in which the government could invest were for human trafficking training for law enforcement, counseling for victims, and legal services for victims.

In the upcoming weeks and months, Farrell and her research partners plan to meet with state and federal legislators to discuss their findings. They also want to work to make their data publically available to activists, scholars, and legislators. "We believe this work will be important in informing legislative responses to human trafficking in the future and helping to guide implementation of new anti-trafficking laws," Farrell said.

Provided by Northeastern University