Professor talks about our need for face-to-face dialogue, in families, classrooms, and workplaces

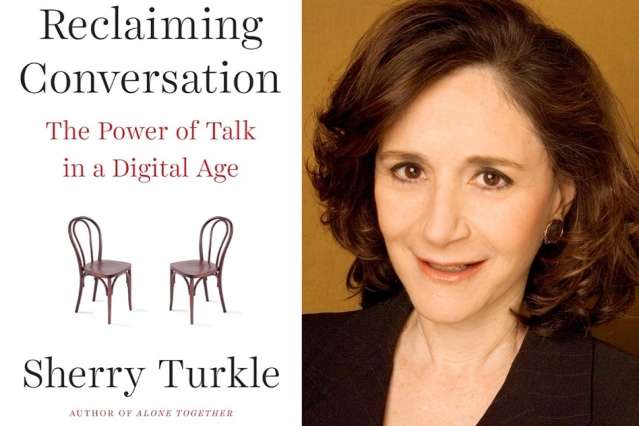

Face it: Many conversations today involve distracted people looking at their phones, not their companions. To Sherry Turkle, the Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology at MIT, the decline in thoughtful face-to-face interaction constitutes an epidemic. Her new book, "Reclaiming Conversation," contends that we need meaningful conversations in our families, classrooms, and workplaces, to help us develop self-knowledge, empathy, and intellectual skills. The book has been widely praised: In The New York Times, Jonathan Franzen wrote that "Turkle's argument derives its power from the breadth of her research and the acuity of her psychological insight." MIT News recently spoke with Turkle about the book.

Q. Your previous book, "Alone Together" (2011), examined some of the isolating effects of technology. How did you move from that to "Reclaiming Conversation," which argues specifically that the erosion in our conversational abilities comes at a huge cost?

A. "Alone Together" was a report on the state of the field as it was. People were telling me: I'd rather text than talk. "Reclaiming Conversation" is looking at what that means: Did people really mean it? Yes, and since it was so, the book became a call to action. It's not an anti-technology book; it's a pro-conversation book. We can enjoy and profit from mobile technology and not give up conversation. I would go further: This is what we have to learn how to do, because conversation is essential to our humanity—and to our creativity, our work, and our ability to be in families.

The disruptive experience I'm trying to capture is that sense that we are so often only partially in a conversation: If you and I are having lunch, and I put up my hand and say, "Just give me a second, I just want to check my phone." I argue that this new experience of being together, but also being elsewhere, is undermining our capacity to have the conversations that count. Or even more simply, experiments show that you can decrease the quality of a conversation and the degree of connection its participants feel toward each other by something as simple as putting a silenced phone on the table between them. So phones diminish empathy. There is in fact a 40 percent decline in all the ways we know how to measure empathy among college students during the past twenty years. But we are resilient. In only five days in a sleepaway camp without their phones, empathy levels come back up. How does this happen? The campers talk to each other.

To the disconnections of our over-connected world, I argue that conversation is the talking cure.

Q. There is a strong generational element to this issue, since children are growing up in a technological environment their parents did not experience. Indeed, you write that we "have embarked on a giant experiment in which our children are human subjects." What are your concerns?

A: We are doing things to our children that people sense are not right. A father remembers giving his [now] 11-year-old daughter baths when she was a baby and toddler, talking to her, and remembers this as a most fulfilling thing, something that deepened their bond. Now he and his wife have a two-year old, and he tells me that when he gives her a bath, he makes sure the water isn't too hot, and then he sits on the toilet seat and does mail on his iPhone. And he tells me, "I know this isn't right."

"Reclaiming Conversation" is not a book of people happily pursuing a new way of life with a mobile technology. On the contrary, I sometimes think of it as a book about unhappy campers. We know we have gotten into patterns that diminish us and haven't decided how to take action.

There is a new Pew Foundation study that showed that 89 percent of adults took out a phone during their most recent social interaction, and 82 percent say that doing so diminished the conversation. Most seriously, we are diminishing the conversations we have with our children. In terms of child development, we are playing with fire. We put our young children in strollers and instead of chatting with them as we walk, we're on our phones, heads down, silent, texting. Parents text during breakfast and dinner. They text in the park. They tell their kids that they have to cut family vacations short because the Wi-Fi is not strong enough in their vacation spots.

As they grow up, our children sense that something is amiss. "Reclaiming Conversation" has story after story of children tugging at the sleeves of their parents during breakfast and dinner. I even have children, for example one 15-year-old, saying, "I don't want to raise my children the way my parents are raising me—with phones out during meals and constantly texting. I want to raise my children the way my parents think they're raising me—with no phones at dinner and conversations at meals."

We are moving from conversation to mere connection in our families. We need to take stock because we won't want to pay the price. A similar thing is happening at the office. We're emailing each other from the next cubicle and we're not having the conversations that increase our sense of engagement and understanding of our co-workers. At work, conversation is good for the bottom line. But it won't happen unless you design for it, make space for it physically, in the layout of the office and in the social space of the office. But the leadership of any business has to be explicit that conversation is a value. It can't happen, for example, if you give employees the signal that they need to be on their email around the clock. It is easy to subvert the possibilities for conversation in our information-intensive world. But it can be done. And remember, parents can't take the time off to have the family conversations that count for so much if their employers expect them online all the time.

Q. In that case what has been the reaction to the book so far, whether in the workplace or beyond?

A: One of my suggestions to managers that I'm getting a lot of positive feedback about is to send out an email that says, "I'm thinking." That sends the message: Don't dumb down your email to me because you're expecting an email response. And it communicates that being online 24/7 is not a value. But I face another reaction that has to do with our new lowered expectations for what conversation is about. Students will say to me, "Instead of coming to office hours, I'll just send a question, and you can just email your response." What's going on here is that students have in mind that they will send me a perfect email and I will send them a perfect answer that responds exactly to their concerns. It is a transactional view of what it means to "talk" to a professor. But no one who became lit up by a love of ideas had this happen because they sent a perfectly crafted email or received one in return. It's more likely that they sat down with a professor with something imperfect and the professor said, "Let's work on this … I'm here for you … So, when are you coming back?" What matters really is the sense of being in a relationship, that someone is committed to you.

That's why dinner table conversations are so important, and office hours are so important: You're coming back, again and again. … What's communicated there is not just acceptance of imperfection. It's the idea that you are building a relationship. You need a conversation for that.

From these past five years of research, I've learned that people are not content with the social mores we have built up around our mobile phones. We have to remember that the ways we do things now are not written in stone. On some things, the path ahead seems clear to me and I've seen that people want to change their ways although it's always hard. We are not looking for solutions; we are looking for first steps. Here are a few: not putting a phone between you and the person you are sharing a meal with; no phones in the kitchen, the dining room, the car. These are sacred spaces for conversation. Give your children an alarm clock so they don't go to sleep with a phone by their side and stay up at night texting. To suggestions like these, the reaction I get is this: This will be hard, but I've been thinking that this might be a good idea already.

Provided by Massachusetts Institute of Technology

This story is republished courtesy of MIT News (web.mit.edu/newsoffice/), a popular site that covers news about MIT research, innovation and teaching.