For trees, growing should not be confused with putting on weight

In coniferous forests across the Northern Hemisphere, woody biomass production does not occur at the same time or rate as changes in tree stem size. This phenomenon presented in this month's issue of Nature Plants was demonstrated and quantified by a large consortium of researchers including three members of the Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL. The time lag observed between changes in tree size and tree mass suggests that these two growth processes exhibit different sensitivities to local environmental conditions such as light, temperature or water availability. These findings have crucial implications for our understanding of carbon cycle.

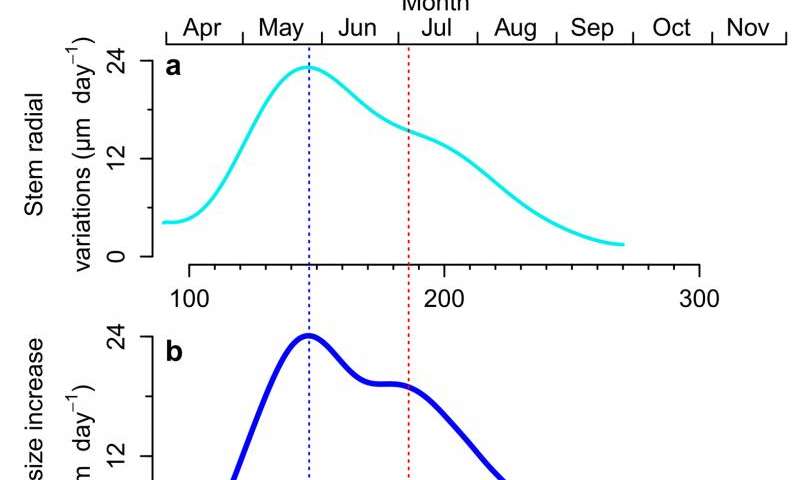

After years of monitoring of tree growth at the cellular scale, the researchers found that during the growing season, the woody biomass production lags behind stem-girth increase by about one month. This key result was presented in an international study led by Henri Cuny, formerly employed by the French National Institute for Agricultural Research INRA and currently working at the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research WSL.

These findings are based upon thousands of cellular observations of wood formation and meteorological data collected at three sites in the Vosges mountains (northeastern France), and complemented by data from over 50 research sites spread across the Northern Hemisphere.

One important site in this network lies in the Lötschental valley, in Valais, Switzerland, along an altitudinal gradient from 800 to 2200 meters ASL. Since 2007, WSL researchers have been conducting high-resolution monitoring of wood formation in Norway spruce and European Larch, two emblematic Swiss species.

Tracking down wood formation with help of microcores

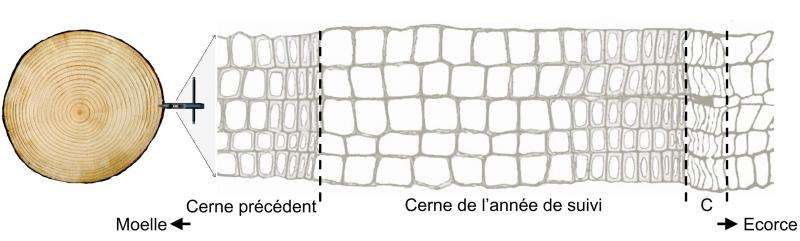

The co-authors of this study collected small wood samples called microcores during several years to precisely quantify the seasonal dynamics of the formation of tracheids, i.e., the cells that make up most of the wood in conifers.

"These samples gave us the ability to watch how individual tree rings are formed and carbon is locked in wood tissue," stated Henri Cuny, the lead author of the paper. He continues, "however, measurements from high-precision instruments called dendrometers that record changes in tree size, showed a different picture: an impressive lag between the carbon allocation to wood and changes in tree size".

Microscopic examination of microcore thin sections revealed that tracheids enlarge in a few days and then build their thick and lignified secondary walls, which can take over 2 months to complete. This developmental sequence is the basis for the significant time lag between the increase in size and the increase in biomass of tree stems.

Crucial implications for our understanding of carbon cycle

The study demonstrates the prevalence of this time lag in coniferous forests in Switzerland and across the Northern Hemisphere in general. The discovered time lag has crucial implications for carbon cycle assessment. For example, it means that the seasonal carbon sequestration into wood cannot be assessed directly from external measurements of stem size changes.

This detailed mechanistic representation of when and how carbon is sequestered into the wood in relation with environmental conditions provides crucial information to assess the impact of climate changes on tree growth and carbon fluxes in forest ecosystems.

-

Fig. 4. Anatomical section of wood realised from a microcore and observed with an optical microscope (× 100). The section contains the typical conifer wood cells, the tracheids. Once these tracheids have been produced by the cambium (C), they enlarge and then reinforce their walls. This developmental sequence is the basis for the significant time lag between the increase in size and the increase in biomass of tree stems. Credit: Henri Cuny, WSL -

Fig. 5. Seasonal dynamics of stem-girth increase, xylem size increase, and woody biomass production. A. Stem radial variations calculated from the external measurements with dendrometers. B. Rate of xylem size increase calculated from the cellular observation of wood formation. C. Rate of woody biomass production calculated from the cellular observation of wood formation. Credit: Henri Cuny, WSL

More information: Henri E. Cuny et al. Woody biomass production lags stem-girth increase by over one month in coniferous forests, Nature Plants (2015). DOI: 10.1038/nplants.2015.160

Journal information: Nature Plants

Provided by Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research