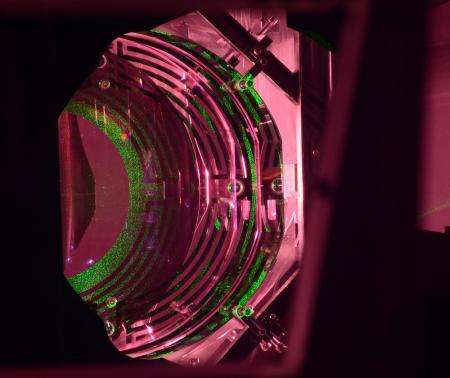

An Advanced LIGO optic that senses gravitational waves. About half of the 100 pound cylindrical optic can be seen. The green light comes from a laser used to help bring the system into an operational state. The maze-like pattern is part of the system to push, twist, and tilt the optic to hold the system in alignment. Credit: Courtesy Caltech/MIT/LIGO Laboratory

The Advanced LIGO Project, a major upgrade of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, is completing its final preparations before the initiation of scientific observations, scheduled to begin in mid-September. Designed to observe gravitational waves—ripples in the fabric of space and time—LIGO, which was designed and is operated by Caltech and MIT with funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF), consists of identical detectors in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington.

"The LIGO scientific and engineering team at Caltech and MIT has been leading the effort over the past seven years to build Advanced LIGO, the world's most sensitive gravitational-wave detector," says David Reitze, the executive director of the LIGO program at Caltech. Groups from the international LIGO Scientific Collaboration also contributed to the design and construction of the Advanced LIGO detector.

Gravitational waves were predicted by Albert Einstein in 1916 as a consequence of his general theory of relativity, and are emitted by violent events in the universe such as exploding stars and colliding black holes. These waves carry information not only about the objects that produce them, but also about the nature of gravity in extreme conditions that cannot be obtained by other astronomical tools.

"Experimental attempts to find gravitational waves have been on going for over 50 years, and they haven't yet been found. They're both very rare and possess signal amplitudes that are exquisitely tiny," Reitze says.

Technicians in Advanced LIGO’s Hanford, Washington control room prepare for its first full-scale operational run later this week. Credit: Courtesy Caltech/MIT/LIGO Laboratory

Although earlier LIGO runs revealed no detections, Advanced LIGO, also funded by the NSF, increases the sensitivity of the observatories by a factor of 10, resulting in a thousandfold increase in observable candidate objects. "The first Advanced LIGO science run will take place with interferometers that can 'see' events more than three times further than the initial LIGO detector," adds David Shoemaker, the MIT Advanced LIGO project leader, "so we'll be probing a much larger volume of space."

Each of the 4-kilometer-long L-shaped LIGO interferometers uses a laser beam split into two beams that travel back and forth through the long arms, within tubes from which the air has been evacuated. The beams are used to monitor the distance between precisely configured mirrors. According to Einstein's theory, the relative distance between the mirrors will change very slightly when a gravitational wave passes by.

The original configuration of LIGO was sensitive enough to detect a change in the lengths of the 4-kilometer arms by a distance one-thousandth the diameter of a proton; this is like accurately measuring the distance from Earth to the nearest star—over four light-years—to within the width of a human hair. Advanced LIGO, which will utilize the infrastructure of LIGO, is much more powerful.

While earlier LIGO observing runs did not confirm the existence of gravitational waves, the influence of such waves has been measured indirectly via observations of a binary system called PSR B1913+6. The system consists of two objects, both neutron stars—the compact cores of dead stars—that orbit a common center of mass. The orbits of these two stellar bodies have been observed to be slowly contracting due to the energy that is lost to gravitational radiation. Binary star systems such as these that are in the very last stages of evolution—just before and during the inevitable collision of the two objects—are key targets of the planned observing schedule for Advanced LIGO.

"Ultimately, Advanced LIGO will be able to see 10 times as far as initial LIGO and, based on theoretical predictions, should detect many binary neutron star mergers per year," Reitze says.

The improved instruments will be able to look at the last minutes of the life of pairs of massive black holes as they spiral closer together, coalesce into one larger black hole, and then vibrate much like two soap bubbles becoming one. Advanced LIGO also will be able to pinpoint periodic signals from the many known pulsars that radiate in the range of 10 to 1,000 Hertz (frequencies that roughly correspond to low and high notes on an organ). In addition, Advanced LIGO will be used to search for the gravitational cosmic background, allowing tests of theories about the development of the universe only 10-35 seconds after the Big Bang.

"We expect it will take five years to fully optimize the detector performance and achieve our design sensitivity," Reitze says. "It has been a long road, and we're very excited to resume the hunt for gravitational waves."

Provided by California Institute of Technology