Breakthrough in understanding the origins of language

Researchers from the "Cognitive Neuroimaging" unit at NeuroSpin have identified a network of brain regions whose organisation may at least partly explain the specificity of the cognitive functions of the human species. These regions are specifically activated in humans but not in macaques, in response to specific changes in a series of recorded auditory sequences.

They coincide with the conventional language areas, especially Broca's area. The language faculty in humans may therefore have its roots in the emergence of a brain circuit capable of integrating information from other brain regions into a coherent whole, within a single region. These results, obtained by a collaboration between the CEA, Inserm, Collège de France, Versailles-Saint-Quentin University and Paris-Sud University, are published in Current Biology.

In this study, conducted at NeuroSpin, Stanislas Dehaene (Professor at the Collège de France, Director of the Unit "Cognitive Neuroimaging" at Inserm/CEA/Paris-Sud University) and Bechir Jarraya (Professor of Neurosurgery at the University of Versailles-Saint-Quentin), with Liping Wang and Lynn Uhrigh, used a non-invasive functional imaging method – functional MRI at 3 Tesla. They exposed three macaques and twenty volunteers to regular auditory sequences, e.g. three identical sounds followed by a different fourth sound (a sequence denoted AAAB). They occasionally played a sequence that violated this regularity, either because it included a different number of sounds (e.g. AAAAAB) or because the sequence of sounds was abnormal (e.g. AAAA, not ending in sound B).

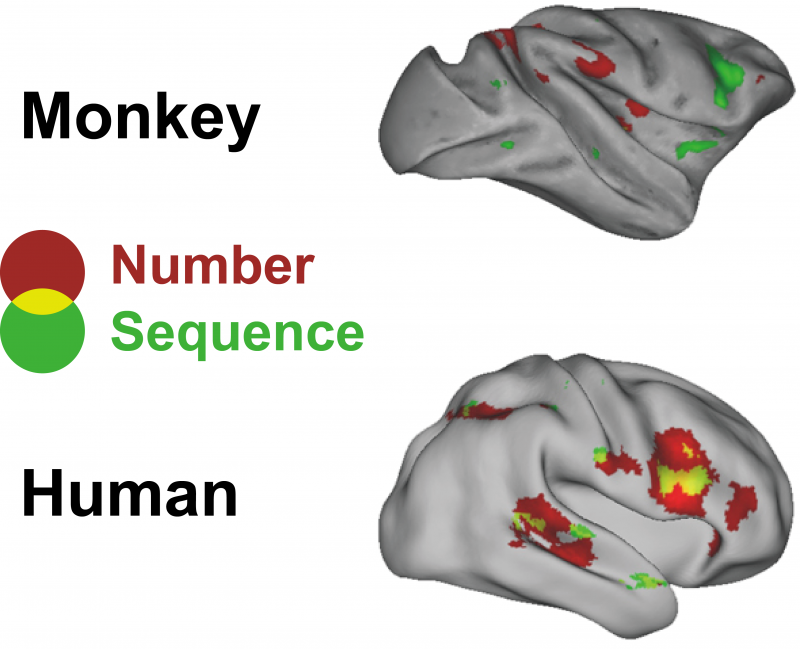

The monkey brain reacted to changes in numbers and sequences, indicating a certain capacity for abstraction. However, it did so in separate, specialised regions for either the number or the sequence. The human brain, by contrast, incorporated both parameters in regions that coincide with the language areas.

Thus, while the monkeys recognised isolated properties such as "four sounds" or "the last is different," evolution seems to have endowed our species with a specific ability to integrate this information into a coherent whole, a formula such as "three sounds, then another" - the beginning of an inner language?

Although the abstract representation of sound sequences is possible in non-human primates, the evolution of a new brain circuit, connected to the auditory areas, could therefore have allowed our species to acquire the unique skill to compose and recognise the complex sequences that characterise human languages.

More information: "Representation of Numerical and Sequential Patterns in Macaque and Human Brains." Current Biology. Jul 22, 2015, doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.035

Journal information: Current Biology

Provided by CEA