Water behavior breakthrough opens a crucial door in chemistry

(Phys.org) —A multi-institutional team has resolved a long-unanswered question about how two of the world's most common substances interact.

In a paper published June 30, 2014, in the journal Nature Communications, Manos Mavrikakis, the Paul A. Elfers professor of chemical and biological engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and his collaborators report fundamental discoveries about how water reacts with metal oxides. The paper, "Water clustering on nanostructured iron oxide films," opens doors for greater understanding and control of chemical reactions in fields ranging from catalysis to geochemistry and atmospheric chemistry.

"These metal oxide materials are everywhere, and water is everywhere," Mavrikakis says. "It would be nice to see how something so abundant as water interacts with materials that are accelerating chemical reactions."

These reactions play a huge role in the catalysis-driven creation of common chemical platforms such as methanol, produced on the order of 10 million tons per year for uses including fuel and as raw material for chemicals production. "Ninety percent of all catalytic processes use metal oxides as a support," Mavrikakis says. "Therefore, all of the reactions including water as an impurity or reactant or product would be affected by the insights developed."

Chemists understand how water interacts with many non-oxide metals, which are very homogeneous. Metal oxides are trickier: An occasional oxygen atom is missing, causing what Mavrikakis calls "oxygen defects." When water meets with one of those defects, it forms two adjacent hydroxyls—a stable compound comprising one oxygen atom and one hydrogen atom.

Mavrikakis, with assistant scientist Guowen Peng and PhD student Carrie Farberow, along with researchers at Aarhus University in Denmark and Lund University in Sweden, investigated how hydroxyls affect water molecules around them, and how that differs from water molecules contacting a pristine metal oxide surface.

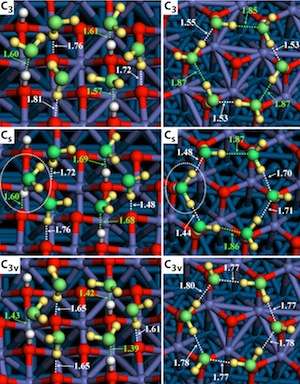

The Aarhus researchers generated data on the reactions using scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). The Wisconsin researchers then subjected the STM images to quantum mechanical analysis that decoded the resulting chemical structures, defining which atom is which. "If you don't have the component of the work that we provided, there is no way that you can tell from STM alone what the atomic-scale structure of the water is, when absorbed on various surfaces" Mavrikakis says.

The project yielded two dramatically different pictures of water-metal oxide reactions.

"On a smooth surface, you form amorphous networks of water molecules, whereas on a hydroxylated surface, there are much more structured, well-ordered domains of water molecules," Mavrikakis says.

In the latter case, the researchers realized that hydroxyl behaves as a sort of anchor, setting the template for a tidy hexameric ring of water molecules attracted to the metal's surface.

Mavrikakis' next step is to examine how these differing structures react with other molecules, and to use the research to improve catalysis. Mavrikakis sees lots of possibilities outside his own field.

"Maybe others might be inspired and look at the geochemistry and/or atmospheric chemistry implications, such as how these water cluster structures on atmospheric dust nanoparticles could affect cloud formation, rain, and acid rain," Mavrikakis says.

Other researchers might also look at whether other molecules exhibit similar behavior when they come into contact with metal oxides, he adds.

"It opens the doors to using hydrogen bonds to make surfaces hydrophilic or attracted to water, and to templating these surfaces for the selective absorption of other molecules possessing fundamental similarities to water," Mavrikakis says. "Because catalysis is at the heart of engineering chemical reactions, this is also very fundamental for atomic-scale chemical reaction engineering."

While the research fills part of the foundation of chemistry, it also owes a great deal to state-of-the-art research technology.

"The size and nature of the calculations we had to do probably was not feasible until maybe four or five years ago, and the spatial and temporal resolution of scanning tunneling microscopy was not there," Mavrikakis says. "So it's advances in the methods that allow for this new information to be born."

More information: "Water clustering on nanostructured iron oxide films." Lindsay R. Merte, et al. Nature Communications 5, Article number: 4193 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5193. Received 12 May 2013 Accepted 22 May 2014 Published 30 June 2014

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by University of Wisconsin-Madison