Space-tested fluid flow concept advances infectious disease diagnoses

A new medical-testing device is being prepped to enter the battle against infectious disease. This instrument could improve diagnosis of certain diseases in remote areas, thanks in part to knowledge gained from a series of investigations aboard the International Space Station on the behavior of liquids. The device uses the space-tested concept of capillary flow to diagnose infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis.

David Kelso, Ph.D., a researcher at Northwestern University in Evanston, Ill., had been working for several years to develop a simple, inexpensive device that could be used in resource-limited settings to test for infectious diseases. When designs didn't work as expected in the lab, Kelso brought in Portland State University researcher Mark Weislogel, Ph.D., who is the principal investigator for the Capillary Flow Experiment (CFE) on the space station.

"He came by the lab, we ran two or three experiments for him, and he explained to us that the problem had to do with capillary flow," Kelso says. "Our mindset was that gravity would pull fluids through the device, but his mindset, due to his work in microgravity, was to use capillary action. His experience and work in zero-G was invaluable; he could look at something and not be constrained to just seeing the effects of gravity but other effects that we were blind to."

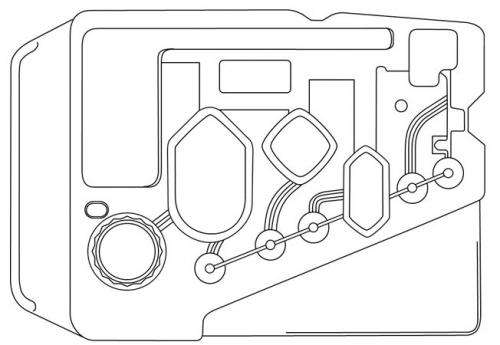

Cell samples in the form of blood or other bodily fluids are put into the device, where an enzyme fluid bursts the cells to release DNA or RNA. Another solution washes away the enzyme and the cellular debris, leaving behind the DNA or RNA, which is captured on a bead and used to identify infectious viruses. "You only need fewer than a dozen particles, and you can detect the presence of the virus," Kelso explains. "It's a phenomenal analytical technique, but it involves four different fluids that have to be moved around."

That's where capillary forces come into play. The interaction between a liquid and a solid that draws a fluid up a narrow tube, capillary forces continue to operate in microgravity, and the low-gravity environment on the space station enabled researchers to conduct investigations into the special dynamics of this fluid behavior. The CFE series clarified the properties of the boundary between a liquid and the solid surface of its container and the flow of liquids under certain conditions. This knowledge will prove useful in designing fluid-bearing containers such as propellant tanks and water storage and management systems. It also will aid in creating instruments that use bio-fluids - including the medical testing device the Northwestern lab is developing.

"The capillary flow knowledge is just amazing," Kelso says. "It's a way to move fluids without putting any energy into the device. We were using motors and batteries and all these things that consume power to make the device work. Doing it with capillary action uses much less energy." That makes it possible to diagnose infectious diseases in places where there is no power or where power is unreliable. It also reduces the time between sample collection and diagnosis and, therefore, initiation of treatment.

"This cartridge and the way fluid moves in it are an important part of measuring viral load level," says Kara Palamountain, president of the Northwestern Global Health Foundation. "Capillary flow helped us understand more about our assumptions and explains the movement we see in the cartridge, which we wouldn't have seen otherwise.

"There are shortages of health care workers of all cadres, from lab technician to community health care workers, so the less constraint we put on the end user the better," she adds. "This wouldn't necessarily require a lab technician or even a lab. It frees up a health care worker." The ability to easily and inexpensively test viral load also makes it possible to monitor the effectiveness of anti-viral medications in the field.

The researchers plan to conduct field studies of the testing device in Africa by the end of this year. If all goes as expected, space research will have become a new weapon in the battle against infectious diseases in remote corners of Earth.

Provided by NASA/Johnson Space Center