Chernobyl's birds are adapting to ionising radiation

Birds in the exclusion zone around Chernobyl are adapting to – and may even be benefiting from – long-term exposure to radiation, ecologists have found. The study, published in the British Ecological Society's journal Functional Ecology, is the first evidence that wild animals adapt to ionising radiation, and the first to show that birds which produce most pheomelanin, a pigment in feathers, have greatest problems coping with radiation exposure.

According to lead author Dr Ismael Galván of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC): "Previous studies of wildlife at Chernobyl showed that chronic radiation exposure depleted antioxidants and increased oxidative damage. We found the opposite – that antioxidant levels increased and oxidative stress decreased with increasing background radiation."

The Chernobyl disaster, which occurred on April 26 1986, had catastrophic environmental consequences. However, because it remains heavily contaminated by radiation, the region represents an accidental ecological experiment to study the effects of ionising radiation on wild animals.

Laboratory experiments have shown that humans and other animals can adapt to radiation, and that prolonged exposure to low doses of radiation increases organisms' resistance to larger, subsequent doses. This adaptation, however, has never been seen outside the laboratory in wild populations.

Previous studies of the level of antioxidants and oxidative damage at Chernobyl are limited to humans, two bird species and one species of fish. Because different species vary widely in their susceptibility to radiation, this limited data has made it difficult to study how wild animals adapt to radiation exposure.

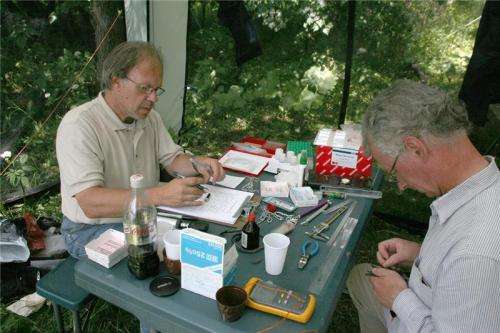

The researchers, including ecologists who have worked around Chernobyl since the 1990s, used mist nets to capture 152 birds from 16 different species at eight sites inside and close to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. They measured background radiation levels at each site, and took feather and blood samples before releasing the birds.

They then measured levels of glutathione (a key antioxidant), oxidative stress and DNA damage in the blood samples, and levels of melanin pigments in the feathers. Melanins are the most common animal pigments but because the production of pheomelanin (one type of melanin, the other type being eumelanin) uses up antioxidants, animals that produce the most pheomelanins are more susceptible to the effects of ionising radiation.

As well as taking samples from 16 different bird species, the team used a novel approach to analyse their results. The method takes better account of how closely related different species are. This is important because some species are more susceptible to radiation than others. The method focuses the analysis on individual birds instead of species averages, making it a much more sensitive way to analyse biochemical responses to radiation.

The results revealed that with increasing background radiation, the birds' body condition and glutathione levels increased and oxidative stress and DNA damage decreased. They also showed that birds which produce larger amounts of pheomelanin and lower amounts of eumelanin pay a cost in terms of poorer body condition, decreased glutathione and increased oxidative stress and DNA damage.

"The findings are important because they tell us more about the different species' ability to adapt to environmental challenges such as Chernobyl and Fukushima," said Galván.

Levels of radiation in the study area ranged from 0.02 to 92.90 micro Sieverts per hour. The 16 bird species surveyed were: red-backed shrike; great tit; barn swallow; wood warbler; blackcap; whitethroat; barred warbler; tree pipit; chaffinch; hawfinch; mistle thrush; song thrush; blackbird; black redstart; robin and thrush nightingale.

Ionising radiation damages cells by producing very reactive compounds known as free radicals. The body protects itself against free radicals using antioxidants, but if the level of antioxidants is too low, radiation produces oxidative stress and genetic damage, which leads to ageing and death.

More information: "Chronic exposure to low-dose radiation at Chernobyl favors adaptation to oxidative stress in birds." Ismael Galván, et al. Functional Ecology, Friday 25 April 2014.. DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.12283

Journal information: Functional Ecology

Provided by British Ecological Society