Ecotoxicity: All clear for silver nanoparticles?

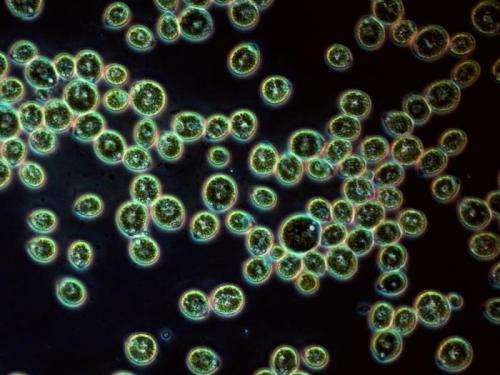

It has long been known that, in the form of free ions, silver particles can be highly toxic to aquatic organisms. Yet to this day, there is a lack of detailed knowledge about the doses required to trigger a response and how the organisms deal with this kind of stress. To learn more about the cellular processes that occur in the cells, scientists from the Aquatic Research Institute, Eawag, subjected algae to a range of silver concentrations.

In the past, silver mostly found its way into the environment in the vicinity of silver mines or via wastewater emanating from the photo industry. More recently, silver nanoparticles have become commonplace in many applications – as ingredients in cosmetics, food packaging, disinfectants, and functional clothing. Though a recent study conducted by the Swiss National Science Foundation revealed that the bulk of silver nanoparticles is retained in wastewater treatment plants, only little is known about the persistence and the impact of the residual nano-silver in the environment.

Infiltrating the energy metabolism undercover

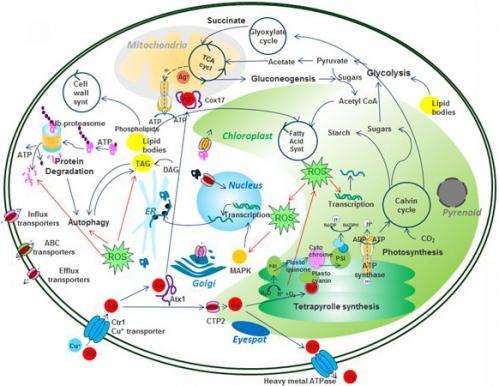

Smitha Pillai from the Eawag Department of Environmental Toxicology and her colleagues from EPFL and ETH Zürich studied the impact of various concentrations of waterborne silver ions on the cells of the green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Silver is chemically very similar to copper, an essential metal due to its importance in several enzymes. Because of that, silver can exploit the cells' copper transport mechanisms and sneak into them undercover. This explains why, already after a short time, concentrations of silver in the intracellular fluid can reach up to one thousand times those in the surrounding environment.

A prompt response

Because silver damages key enzymes involved in energy metabolism, even low concentrations can cut photosynthesis and growth rates by a half in just 15 minutes. Over the same time period, the researchers also detected changes in the activity of about 1000 other genes and proteins, which they interpreted as a response to the stressor – an attempt to repair silver-induced damage. At low concentrations, the cells' photosynthesis apparatus recovered within five hours, and recovery mechanisms were sufficient to deal with all but the highest concentrations tested.

A number of unanswered questions

At first glance, the results are reassuring because the silver concentrations that the algae are subject to in the environment are rarely as high as those applied in the lab, which allows them to recover quickly – at least externally. But the experiments also showed that even low silver concentrations have a significant effect on intracellular processes and that the algae divert their energy to repairing damage incurred. This can pose a problem when other stressors act in parallel, such as increased UV-radiation or other chemical compounds. Moreover, it remains unknown to this day whether the cells have an active mechanism to shuttle out the silver. Lacking such a mechanism, the silver could have adverse effects on higher organisms, given that algae are at the bottom of the food chain.

More information: PNAS DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1319388111

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne