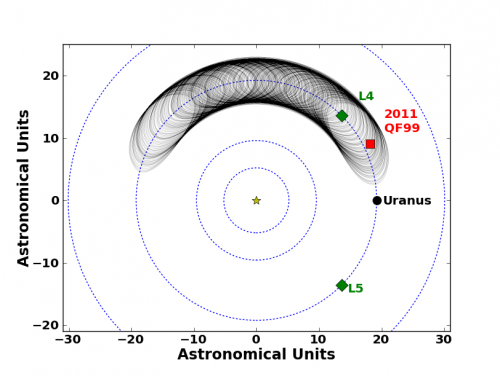

This image shows the motion of 2011 QF99 over the next 59 kyr. Shown here is the trajectory of 2011 QF99, according to the best fit to the observations. The current position is marked by a red square, and the black line shows the trajectory 59 kyr into the future. L4 and L5 are the triangular Lagrange points, the points in space which Credit: UBC Astronomy

University of British Columbia astronomers have discovered the first Trojan asteroid sharing the orbit of Uranus, and believe 2011 QF99 is part of a larger-than-expected population of transient objects temporarily trapped by the gravitational pull of the Solar System's giant planets.

Trojans are asteroids that share the orbit of a planet, occupying stable positions known as Lagrangian points. Astronomers considered their presence at Uranus unlikely because the gravitational pull of larger neighbouring planets would destabilize and expel any Uranian Trojans over the age of the Solar System.

To determine how the 60 kilometre-wide ball of rock and ice ended up sharing an orbit with Uranus the astronomers created a simulation of the Solar System and its co-orbital objects, including Trojans.

"Surprisingly, our model predicts that at any given time three per cent of scattered objects between Jupiter and Neptune should be co-orbitals of Uranus or Neptune," says Mike Alexandersen, lead author of the study to be published tomorrow in the journal Science. This percentage had never before been computed, and is much higher than previous estimates.

Several temporary Trojans and co-orbitals have been discovered in the Solar System during the past decade. QF99 is one of those temporary objects, only recently (within the last few hundred thousand years) ensnared by Uranus and set to escape the planet's gravitational pull in about a million years.

This is one of three discovery images of 2011 QF99 taken from CFHT on 2011 October 24 (2011 QF99 is inside the green circle). This is the first of three images of the same patch of sky, taken one hour apart, that were then compared to find moving light-sources. Credit: UBC Astronomy

"This tells us something about the current evolution of the Solar System," says Alexandersen. "By studying the process by which Trojans become temporarily captured, one can better understand how objects migrate into the planetary region of the Solar System."

A short-term animation showing the motion of 2011 QF99, as seen from above the north pole of the solar system. Credit: UBC

UBC astronomers Brett Gladman, Sarah Greenstreet and colleagues at the National Research Council of Canada and Observatoire de Besancon in France were part of the research team.

More information: "A Uranian Trojan and the Frequency of Temporary Giant-Planet Co-Orbitals," by M. Alexandersen et al. Science, 2013.

Journal information: Science

Provided by University of British Columbia