Credit: 2013 EPFL

Scientists at EPFL have developed a new method for making antimicrobial surfaces that can eliminate bacteria under a minute. The technology, now tested in a hospital, shows enormous potential for preventing hospital-acquired infections.

One of the biggest problems for hospitals is maintaining a sterile environment and protecting its patients from acquiring what are known as nosocomial infections. A way to minimize or prevent this risk altogether is to cover surfaces with antimicrobial films that either kill or stop the growth of micro-organisms like bacteria, fungi or viruses. The problem is that many of these antimicrobial films are often not stable, their preparation methods are hard to industrialize, they are not uniform throughout, and can be wiped off a surface by simply passing over a cloth or a finger. Publishing in Surface & Coatings Technology, EPFL scientists have developed a way to create stable, uniform, and highly-adhesive antimicrobial films with fast antibacterial action, using a new method called Highly Ionized Pulsed Plasma Magnetron Sputtering (HiPIMS).

For over a decade now, scientists have been trying to find a way to battle hospital-acquired infections. Frequent use of antibiotics can lead to the prevalence of resistant bacterial strains ('superbugs'), which limits pharmaceutical solutions. Outside of medicine, the strategy has focused on covering hospital surfaces (e.g. walls, floors, surgical/food trays etc) with antimicrobial films.

Contemporary approaches for manufacturing antimicrobial films utilize sputtering, a method that generates plasma (usually from an argon gas) in a vacuum to knock atoms from a material and deposit them as a thin film onto a surface. But one common problem is that the deposited film is non-uniform when sputtered onto a wrinkled or complex surface. In addition to this, high costs and high temperatures also present obstacles in depositing efficient antimicrobial films.

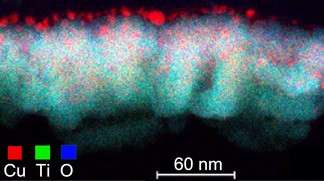

The team of César Pulgarin at EPFL may have found the solution. Using a cutting-edge sputtering technique called HiPIMS to deposit antibacterial titanium oxide and copper (TiO2/Cu) films on 3D polyester surfaces for the first time. Both TiO2 and Cu form a close and homogenous junction on their surfaces. This leads to the production of free radicals, chemicals that are powerful natural bactericides.

The advantage of the new method is that different metal combinations can be explored in a systematic and controlled way, and also that it can deposit ultrathin films with a denser and tougher coating morphology than other traditional methods like sol-gel. This means that the HIPIMS-coated surfaces can be more resistant to corrosion and environmental degradation, making them ideal for use on a range of everyday surfaces.

Traditional antibacterial surfaces also depend heavily on light to work. Unlike previous films, the HiPIMS-deposited TiO2/Cu films can work in-doors and throughout the night because gradual release ("leaching") of Cu ions produce bactericidal effect even in the dark. The EPFL researchers also tested the antibacterial efficiency of the deposited films on the viability of E. coli, a bacterium that is commonly used in preliminary screening tests. By comparing their data with previous studies, the scientists found that the HiPIMS-deposited TiO2/Cu began to slow the growth of attached E. coli at unprecedented bactericidal speeds.

The new technology is expected to impact the way antimicrobial surfaces are implemented and could open new ways to experiment with thin-film deposition on surfaces. Having published their lab-based data, César Pulgarin's group is now collaborating with the University Hospital of Lausanne (CHUV) and the University of Lausanne (UNIL) to test out the new technique on real-life hospital pathogenic microorganisms.

Provided by Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne