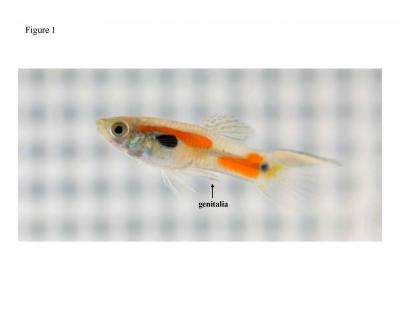

This is a male guppy with the genitalia highlighted. Credit: Photo: Anna Price

Some males will go to great lengths to pursue a female and take extreme measures to hold on once they find one that interests them, even if that affection is unrequited. New research from evolutionary biologists at the University of Toronto shows that the male guppy grows claws on its genitals to make it more difficult for unreceptive females to get away during mating.

Genitalia differ greatly in animal groups, even among similar species – so much so that even closely related species may have very different genitalia. The reasons for these differences are unclear but sexual conflict between males and females may be a source. Sexual conflict occurs when the fitness interests of males and females differ, which is rooted in differences in egg and sperm sizes. Males invest less than females in reproduction because sperm is cheap to produce, and larger eggs are most costly to make. This difference results in a conflict in which males are interested in mating with as many females possible but females are more selective with their mates.

The researchers examined the role of a pair of claws at the tip of the gonopodium of the male guppy (Poecilia reticulata) – essentially the fish's penis.

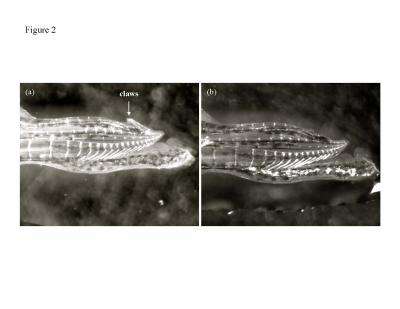

This shows the tip of the genitalia of a male guppy with the claws (a) intact and (b) surgically removed. Credit: Photo: Lucia Kwan

"Our results show that the claws are used to increase sperm transfer to females who are resisting matings," says Lucia Kwan, PhD candidate in U of T's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and lead author of a paper published this week in Biology Letters. "This suggests that it has evolved to benefit males at the expense of females, especially when their mating interests differ."

The researchers tested two ideas for the function of the claws – one for their role in securing sperm in place at the tip of the gonopodium just before it is inserted into the female, the other for grasping unreceptive or resistant females during mating to aid in sperm transfer. For the latter, Kwan, former graduate student Yun Yun Cheng and faculty members Helen Rodd and Locke Rowe used a phenotypic engineering approach. They surgically removed the pair of claws from one set of males and compared the amount of sperm transferred by them with a group of males who hadn't been declawed after they had all mated with receptive or unreceptive females.

"Clawed males transferred up to three times more sperm to unreceptive females compared to declawed males," says Kwan. "The claw has evolved to benefit the males at the expense of females, and implicates sexual conflict between the sexes in the diversification of the genitalia in this family of fish. This provides support that this important selective force is behind an evolutionary pattern that evolutionary biologists have been trying to unravel for over a century."

More information: The results of the study are described in a paper titled "Sexual conflict and the function of genitalic claws in guppies (Poecilia reticulata)" published this week in Biology Letters.

Journal information: Biology Letters

Provided by University of Toronto