Cannibal tadpoles key to understanding digestive evolution

A carnivorous, cannibalistic tadpole may play a role in understanding the evolution and development of digestive organs, according to research from North Carolina State University. These findings may also shed light on universal rules of organ development that could lead to better diagnosis and prevention of intestinal birth defects.

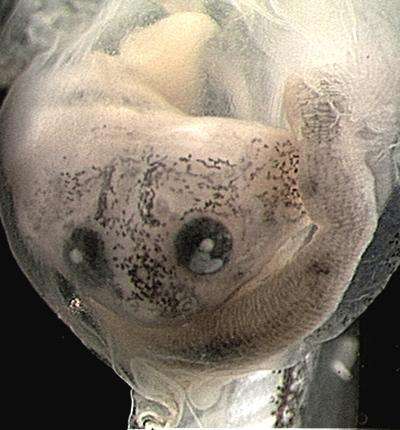

NC State developmental biologist Nanette Nascone-Yoder, graduate student Stephanie Bloom and postdoc Cris Ledon-Rettig looked at Xenopus laevis (African clawed frog) and Lepidobatrachus laevis (Budgett's frog) tadpoles. These frog species differ in diet and last shared a common ancestor about 110 million years ago. Like most tadpoles, Xenopus exist primarily on a diet of algae, and their long, simple digestive tracts are not able to process insects or proteins until they become adult frogs. Budgett's is an aggressive species of frog which is carnivorous – and cannibalistic – in the tadpole stage.

Nascone-Yoder knew that Budgett's tadpoles had evolved shorter, more complex guts to digest protein much earlier in their development. She and her team exposed Xenopus embryos to molecules that inactivated a variety of genes to see if any might coax Xenopus to develop a more carnivore-like digestive tract. Remarkably, five molecules caused Xenopus tadpoles to develop guts that were closer in appearance to those of the Budgett's tadpoles. Taking it one step further, Nascone-Yoder exposed Budgett's frog embryos to molecules with opposite effects, and got tadpole guts that were closer to those of Xenopus.

"Essentially, these molecules are allowing us to tease apart the processes that play a key role in gut development," Nascone-Yoder says. "Understanding how and why the gut develops different shapes and lengths to adapt to different diets and environments during evolution gives us insight into what types of processes can be altered in the context of human birth defects, another scenario in which the gut also changes its shape and function."

The researchers' next steps include finding out whether the changes in these gut tubes were merely cosmetic, or if they also function (digest) differently.

More information: "Developmental origins of a novel gut morphology in frogs", Evolution and Development, 2013.

Abstract

Phenotypic variation is a prerequisite for evolution by natural selection, yet the processes that give rise to the novel morphologies upon which selection acts are poorly understood. We employed a chemical genetic screen to identify developmental changes capable of generating ecologically relevant morphological variation as observed among extant species. Specifically, we assayed for exogenously applied small molecules capable of transforming the ancestral larval foregut of the herbivorous Xenopus laevis to resemble the derived larval foregut of the carnivorous Lepidobatrachus laevis. Appropriately, the small molecules that demonstrate this capacity modulate conserved morphogenetic pathways involved in gut development, including downregulation of retinoic acid (RA) signaling. Identical manipulation of RA signaling in a species that is more closely related to Lepidobatrachus, Ceratophrys cranwelli, yielded even more similar transformations, corroborating the relevance of RA signaling variation in interspecific morphological change. Finally, we were able to recover the ancestral gut phenotype in Lepidobatrachus by performing a reverse chemical manipulation to upregulate RA signaling, providing strong evidence that modifications to this specific pathway promoted the emergence of a lineage-specific phenotypic novelty. Interestingly, our screen also revealed pathways that have not yet been implicated in early gut morphogenesis, such as thyroid hormone signaling. In general, the chemical genetic screen may be a valuable tool for identifying developmental mechanisms that underlie ecologically and evolutionarily relevant phenotypic variation.

Provided by North Carolina State University