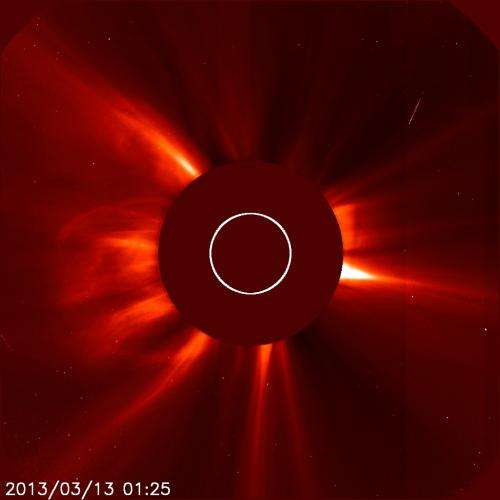

ESA and NASA's Solar Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) captured this image of a coronal mass ejection bursting off the leftside of the image at 9:25 p.m. EDT on March 12, 2013. This sun itself is obscured in this image, called a coronagraph, in order to better see the dimmer structures around it. Credit: ESA&NASA/SOHO

The sun recently erupted with two coronal mass ejections (CMEs). One began at 8:36 p.m. EDT on March 12, 2013 and is directed toward three NASA spacecraft, Spitzer, Kepler and Epoxi. There is, however, no particle radiation associated with this event, which is what would normally concern operators of interplanetary spacecraft since the particles can trip computer electronics on board. A second CME began at 6:54 a.m. EDT on March 13, 2013 and its flank may pass by Earth at a speed that does not typically have a significant impact at Earth.

Experimental NASA research models, based on observations from the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) and ESA/NASA's Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, indicate that both CMEs left the sun at around 400 miles per second, which is a fairly typical speed for CMEs.

Not to be confused with a solar flare, a CME is a solar phenomenon that can send solar particles into space and reach Earth one to three days later.

Earth-directed CMEs can cause a space weather phenomenon called a geomagnetic storm, which occurs when they connect with the outside of Earth's magnetic envelope, the magnetosphere, for an extended period of time. In the past, geomagnetic storms from CMEs of this speed are usually mild. CMEs such as this have caused auroras near the poles but are unlikely to disrupt electrical systems on Earth or interfere with GPS or satellite-based communications systems.

Provided by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center