Polar bears stand on Russia's Wrangel island on October 2003. A major meeting of governments on threats to endangered species rejected a ban on international trade in polar bears amid fears it would distract from the bigger threat of global warming.

A major meeting of governments on threats to endangered species on Thursday rejected a ban on international trade in polar bears amid fears it would distract from the bigger threat of global warming.

The proposal had divided conservationists, who agree that the main risk to the world's largest carnivorous land animal comes from habitat loss but differ over whether international trade also puts the bears at risk of extinction.

Polar bears are widely seen as the animal on the front line of global warming and will be hit-hard by melting polar ice caps.

But the debate among the 178 member nations of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) meeting in Bangkok focused on the additional threat to the species posed by its international trade.

"The polar bear is facing a grim future, and today brought more bad news," Dan Ashe, head of the US delegation which proposed the ban. He warned the polar bear population could decline by two-thirds by 2050.

"The continued harvest of polar bears to supply the commercial international trade is not sustainable," Ashe said.

The ban was rejected by 42 votes to 38, with 46 abstentions among the nations who participated in the poll in Bangkok.

The proposal, which needed support from a two-third majority, can be re-examined at a plenary session of the 178 CITES member nations next week. A similar bid was unsuccessful at the last CITES meeting in 2010.

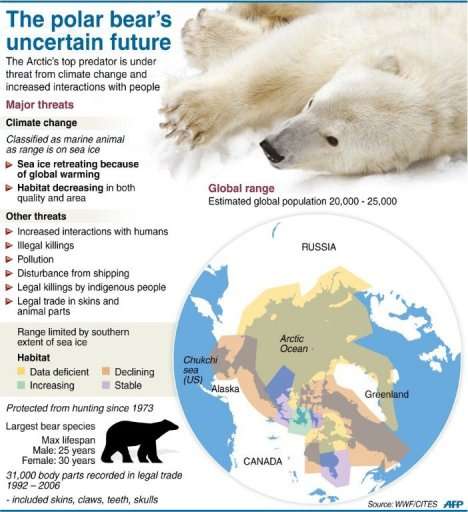

Graphic fact file on polar bears. A major meeting of governments on threats to endangered species on Thursday rejected a ban on international trade in polar bears amid fears it would distract from the bigger threat of global warming.

Polar bears are prized for their skins—particularly in Russia—as well as other body parts such as skulls, claws and teeth.

The animals are currently listed on Annex II of CITES, which imposes strict controls over their international trade.

About half of the roughly 800 polar bears killed each year end up in the international trade, mostly wild bears from Canada, according to expert estimates cited by the US.

The United States, Canada, Russia, Denmark (Greenland) and Norway host a global population of 20,000 to 25,000 polar bears.

But even some major conservation organisations such as Traffic and WWF declined to support the US proposal for a complete ban on international trade, saying climate change is a far bigger threat.

According to the WWF, "habitat loss from climate warming, not international trade, is the primary driver" of an expected population decline.

Canada, which hosts the largest portion of the global population of polar bears and is the only country that still exports polar bear parts, opposes a ban.

It cites the need to preserve the traditions of the Inuit, an indigenous minority living mostly in the north of the country.

"The polar bear advances strong emotion. It is an iconic symbol of the Arctic," said Canadian delegate Basile Van Havre.

Canada "is committed to the protection of the species but that doesn't mean that emotion should be guiding criteria for decision making here nor for the proper management of the species", he added.

Inuit parliamentarian Tagak Curley told the conference his people had "a unique relation with polar bears".

"Modern management has been in place for more than 40 years. During this time the population of polar bears in Canada has more than doubled," he said.

"Our identity as Inuit would be weaker without the polar bear. We are connected to the polar bears in a very special way."

Some campaign groups did however support an international ban, along with Russia, which says sky-high prices—up to $50,000 for a pelt in its country—encourages poaching of its own polar bears.

(c) 2013 AFP