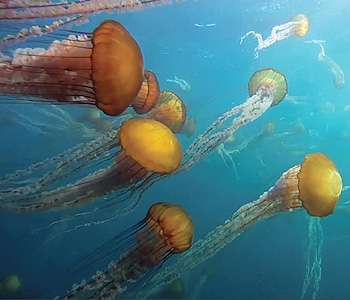

A swarm of Chrysaora jellies swims near the surface of Monterey Bay. These jellies bloom periodically along the California coast. This image was taken by a video camera mounted on MBARI's long-range autonomous underwater vehicle. Credit: 2010 MBARI.

A surge in jellyfish blooms over the past decade has spawned similar blooms of public fascination with these sea drifters and their apparent saturation of our oceans. Images of fish nets and nuclear-plant intake pipes clogged with gelatinous sacks of tentacles have flared concerns for fisheries and public safety. But recent work from an international team of marine scientists, including MBARI biologist Steve Haddock, suggests that this recent population explosion might only reflect half of the jellyfish story.

In the largest-scale jellyfish study to date, the scientists reviewed records of jelly sightings from 37 regions around the world dating from 1874 to 2011. Through a series of statistical tests, the researchers discovered a cyclic pattern to the jellyfish blooms, with peaks roughly every 20 years. The recent jellyfish pulse might thus be a snapshot within a long series of natural cycles, the team notes in the December Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The researchers found this decadal cycle throughout the entire 137-year dataset, but only detected a statistically significant pattern within the past 40 years. This could represent a real change through time, or might just reflect gaps in the available data.

"It's hard to separate out the lack of data from the lack of jellyfish," said Haddock. "Nobody writes a paper about how there are no jellyfish out there."

The team did detect a weak statistically significant rise in jellyfish populations within the past 40 years, though the signal was not as strong as previous studies have suggested. Haddock believes that most of those studies employed inadequate statistical tests, fitting straight lines through data points that behaved cyclically.

"I just don't think that type of analysis is really relevant," he said.

Instead, his team took a more nuanced statistical approach that revealed the waxing and waning pattern amidst an underlying linear trend.

Though weak, this upward trend does call into question why jellyfish populations might have started to increase in recent decades.

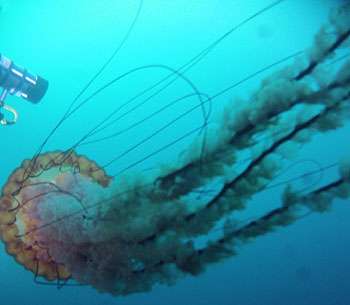

Chrysaora jelly photographed by the Self Contained Plankton Imager (SCPI) during its first field test in Monterey Bay in February 2013. Credit: 2013 MBARI

Climate change, the commonly cited culprit, might indeed be speeding up jellyfish growth due to increasing seawater temperatures. But this is just one of many shifting environmental conditions that favor jellyfish growth. Human waste and agricultural runoff, for example, have fertilized and expanded blooms of plankton and may increase the food supply to jellyfish. Such pollutants also deplete dissolved oxygen to levels that most marine organisms cannot withstand but that some jellyfish can handle.

Such environmental changes, compounded by a recent upswing in the natural jellyfish bloom-and-bust cycle, have likely caused the recent explosion that worries coastal communities.

The SCPI camera took this portrait of project manager Chad Kecy (left) and lead scientist Steve Haddock (right) immediately after its first field test in Monterey Bay. Credit: 2013 MBARI

"The biggest effects are on fisheries, either directly interfering with the nets or competition between the jellyfish and fish," said Haddock. "Both of those things seem to have been a problem in the past."

But, Haddock pointed out, jelly populations have also been declining in some regions of the world. For example, jellyfish abundance has rapidly declined off the coast of India, where increasing culinary interest in the floaters threatens the sea turtles that feed on them.

"It's not just a matter of jellyfish being evil and we need to figure out a way to prevent them from growing," Haddock said. "They have a natural place in the ecosystems."

Jelly-cams could help clarify future trends

To better grasp the underlying trends in jellyfish growth, the team hopes to expand the geographic scope of their data. To do this, Haddock is working with MBARI engineers to develop a cheap and easily deployable camera that researchers could potentially use around the world to collect more widespread jelly sightings.

"Ideally these cameras would be really cheap so that every city or harbor or community could have one," Haddock said. "That is one of the best ways that you can quantify jellyfish."

MBARI engineers have been working on a prototype of the camera, called SCPI (Self Contained Plankton Imager), for nearly a year. Last week, the team attached the camera to MBARI's remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Ventana and performed their first field test. They are now making adjustments to the system, and will continue to conduct field tests in the coming months.

Ultimately, the team plans to make the SCPI camera design available through open-source documents so that engineers elsewhere can easily replicate it. Haddock also hopes to secure funds to attach a SCPI camera onto one of MBARI's autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV), to collect continuous records of jellies and other animals at various ocean depths. Meanwhile, the team will continue compiling anecdotal records of jellyfish through a program called Jellywatch, which aggregates jellyfish sightings from people around the world.

Since the jelly cycles take decades to pan out, real changes in jellyfish abundances might take 60 or 100 years to appear clearly. But Haddock is hopeful that increased documentation with SCPI and other similar programs will expedite the process.

"If we had better ways to quantify jellies from year to year, over larger areas, I think we could see the pattern a lot more clearly even within one or two more cycles," he said.

Until then, researchers will keep an eye out for a global lull in jellyfish blooms within the next decade as we drift into a downswing of the natural cycle.

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute