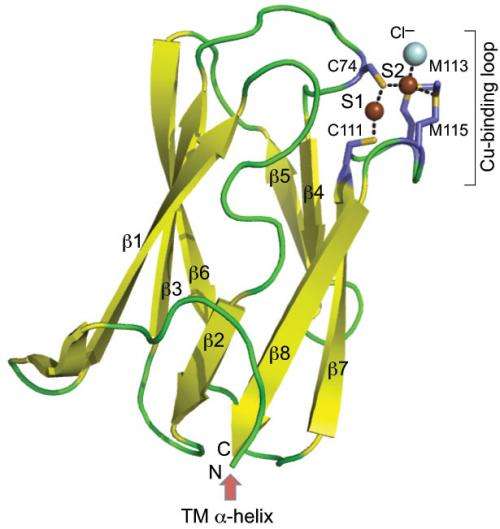

A ribbon diagram depicts the three-dimensional structure of the copper-binding protein CupA found in the respiratory pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae.

(Phys.org)—A team of chemists and biologists led by Indiana University chemistry professor David Giedroc has described a previously unknown function of a protein they now know is responsible for protecting a major bacterial pathogen from toxic levels of copper. The results were published Jan. 27 in Nature Chemical Biology.

Bacterial pathogens like Streptococcus pneumoniae—responsible for infections that include pneumonia, meningitis and sepsis—have evolved various strategies to limit copper levels in their cells to prevent toxicity.

"Copper is highly reactive metal and is carefully handled by all cells that require it. There is emerging evidence to suggest that human cells use copper toxicity as a weapon to kill microbial pathogens," Giedroc said. "The novel copper trafficking system that we describe in this paper represents a new functional twist on an evolutionary ancient family of proteins that opens up a potential new antibacterial strategy."

Giedroc and co-workers describe the structure and function of the protein CupA as a chaperone that buffers copper to very low concentrations—in turn protecting S. pneumoniae from damage.

"We're proposing that the primary role of CupA in S. pneumoniae is to bind copper ions near the plasma membrane as soon as they enter the cell and, after diffusion of copper-bound CupA in the membrane, to deliver copper directly to the exporter CopA, which extrudes copper out of the cell," Giedroc said.

Copper chaperones are known to exist in all cells from bacteria to humans. In this report, the authors describe a completely novel way in which a copper chaperone and a domain of a copper recipient target protein, CopA, bind copper. Using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy—a technique to obtain mechanistic and structural information about molecules—they were able to determine the pathway by which copper is transferred from CupA to CopA.

"This work represents an excellent example of collaborative science that works so well on the Bloomington campus, teaming up structural biologists, a microbiologist and an inorganic chemist," Giedroc said. "This allowed us to grasp the biological significance of what is essentially novel coordination chemistry that bacteria use to protect themselves from copper-mediated killing."

Journal information: Nature Chemical Biology

Provided by Indiana University