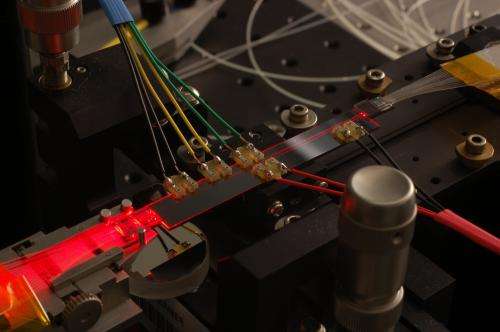

The 8-cm-long silica-on-silicon photonic chip in the center of the picture served as the 4-photon QBSM. Arrays of single-mode fibers are glued to the left and right sides of the chip. For viewing purposes, a red laser is coupled into two of the single mode fibers (right side of picture), which illuminate a portion of the on-chip interferometric network. For the boson sampling experiment, the red laser was replaced with single photon sources. There are five thermal phase shifting elements on top of the chip, though they were not used in this experiment. This image relates to the paper by Dr. Spring and colleagues. Credit: Dr. James C. Gates

(Phys.org)—Separate teams working on boson samplers report progress in separate papers uploaded to the preprint server arXiv and in the journal Science. Each relate the progress being made in developing a quantum version of a Victorian era Galton board – where balls are dropped across a peg board resulting in the representation of a binomial distribution at the bottom.

While interest remains high in creating a true quantum computer, thus far, real world results have been less than promising. Because of that, some experts in the field have suggested that perhaps what's needed is a new way of looking at the problem. MIT's Scott Aaronson, for example, has suggested that rather than trying to start by building a quantum computer from the ground up, a better approach might be to build specialty devices that solve just one type of problem. He has suggested that a Galton board created using quantum mechanics principles should be possible. In response, several research teams around the globe have been trying to do just that.

Quantum versions of the Galton board take the form of a board that uses photons instead of wooden balls and pegs and are named after the family of particles to which they belong: bosons. The sampling devices work much the same as the Victorian models except in one important way. When a photon in the sampler meets another photon, both must go left, or right – in the real-world physical board, balls can go individually either way on their own. The result should be a device that can calculate far faster than any conventional computer.

Using such a setup, one team, led by Justin Spring, has built a sampler capable of computing the permanent of a matrix. Another led by Matthew Broome, has sent three photons through a maze that describe a 6 node optical circuit.

What's perhaps most compelling about the work being done by all of the teams in this area is the promise of scalability. Not in making the boards or balls bigger, but in making the samplers more and more complex by adding more ways that the photons can be manipulated as they move through the device. Theoretically, doing so offers the promise of a universal computer capable of performing limitless numbers of applications. Whether it will be possible to construct such complex devices in the real world however, remains to be seen.

More information: Photonic Boson Sampling in a Tunable Circuit, Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.1231440

ABSTRACT

Quantum computers are unnecessary for exponentially efficient computation or simulation if the Extended Church-Turing thesis is correct. The thesis would be strongly contradicted by physical devices that efficiently perform tasks believed to be intractable for classical computers. Such a task is boson sampling: sampling the output distributions of n bosons scattered by some linear-optical unitary process. Here, we test the central premise of boson sampling, experimentally verifying that 3-photon scattering amplitudes are given by the permanents of submatrices generated from a unitary describing a 6-mode integrated optical circuit. We find the protocol to be robust, working even with the unavoidable effects of photon loss, non-ideal sources, and imperfect detection. Scaling this to large numbers of photons will be a much simpler task than building a universal quantum computer.

Boson Sampling on a Photonic Chip, Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.1231692

ABSTRACT

While universal quantum computers ideally solve problems such as factoring integers exponentially more efficiently than classical machines, the formidable challenges in building such devices motivate the demonstration of simpler, problem-specific algorithms that still promise a quantum speedup. We construct a quantum boson sampling machine (QBSM) to sample the output distribution resulting from the nonclassical interference of photons in an integrated photonic circuit, a problem thought to be exponentially hard to solve classically. Unlike universal quantum computation, boson sampling merely requires indistinguishable photons, linear state evolution, and detectors. We benchmark our QBSM with three and four photons and analyze sources of sampling inaccuracy. Scaling up to larger devices could offer the first definitive quantum-enhanced computation.

Arxiv papers: arxiv.org/abs/1212.2783 and arxiv.org/abs/1212.2240

© 2012 Phys.org