ALMA: New telescope can detect hidden gases that might hold the key to star and planetary formation

At first glance, the bone-dry landscape of the Atacama Desert in Chile might seem inhospitable.

But, it's prime real estate for astronomers. This desert is now home to the largest ground-based radio telescope in the world!

The telescope is called the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or "ALMA for short. And, it's allowing us to see the universe like we never have before," says Kartik Sheth, an astronomer with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Charlottesville, Va.

"ALMA will be a telescope made up of 66 antennas, at 16,500 feet, in the desert of Atacama, in Chile," he explains.

With support from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Sheth is part of a team of astronomers putting this new array to work. "Together, these telescopes work as a single telescope that can be as large as 10 miles in diameter. And, it will be 10-to-100 times more powerful than any existing telescope that we have," says Sheth.

"ALMA realizes a decades-long dream of many astronomers and engineers, and is a testament to the tremendous skill of a large team at the NRAO and of our international partners," says Phil Puxley, NSF's program director for ALMA and NRAO.

From its perch in the high desert, ALMA sits above 40 percent of the Earth's atmosphere and virtually all of the world's water vapor. ALMA is designed to peer into a slice of the electromagnetic spectrum at millimeter wavelengths—light that is closer to a radio wave than to the optical light that is seen by the human eye.

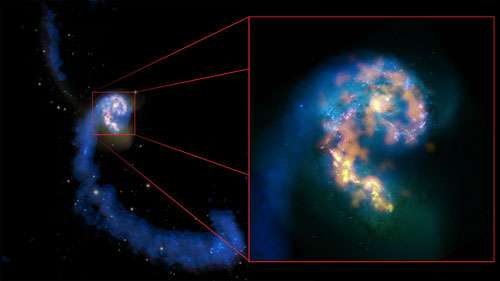

"We're pushing the boundaries of technology in every aspect with ALMA. We have state-of-the-art antennas that are so accurately machined that they deviate from perfect parabolic shapes by less than the width of a human hair across the entire 40-foot surface," explains Sheth. "ALMA has the ability to map the dust and gas in galaxies with the same power, the same sensitivity and resolution from the nearest galaxies to the most distant ones, which are also the youngest ones."

That's critical for him because Sheth studies the evolution of galaxies, and ALMA can look where optical telescopes can't look. "ALMA can see where the dust is located. And, we're now able to understand how much gas there must be, and how much fuel there is for a black hole," he adds.

Sheth says ALMA can detect hidden gases inside galaxies—gases that might hold the key to star and planetary formation. ALMA might even detect the building blocks of life.

"Understanding the different types of galaxies, how they formed, and how they change over time is really giving us a key piece of the jigsaw puzzle in understanding how the universe formed, and ultimately how planets formed and how we came to be here today," he says.

Provided by National Science Foundation