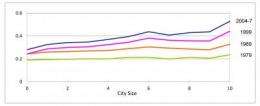

The graph above tracks the income gap in different sized cities, with “0” representing rural areas and “10” the nation’s largest metropolitan regions. As shown, in 1979 (the green line), wage inequality was roughly equal regardless of where workers resided. Not so today. Now, the larger the city, the wider the wage gap among its workers. These income extremes grew steeper with each successive decade. Credit: Inequality and City Size by Nathanial Baum-Snow and Ronni Pavan

Why in the United States are the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer?

Part of the answer lies in the unique economies of our larger cities, finds a study by Ronni Pavan of the University of Rochester and Nathaniel Baum-Snow of Brown University and the National Bureau of Economic Research.

"Our results show that overall up to one-third of the growth in the wage gap between the rich and the poor is driven by city size independent of workers' skills," says Pavan.

Using U.S. Census data and American Community Surveys from 1980 to 2007 across the entire United States, Pavan and Baum-Snow found that the larger the city, the wider the wage gap among its workers. In other words, the country's largest cities, New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, are home to the greatest extremes in incomes, while midsized cities experience relatively less wage inequality and rural areas the least.

So what's behind the mega income gap in megacities? The soaring salaries of many urban dwellers, conclude the authors.

Larger metropolitan areas, more so than their smaller counterparts or rural areas, have experienced rapid growth in wages within all skill levels, the study finds. From high school dropouts to professionals, many workers in large metropolitan regions have enjoyed fatter paychecks. At the same time, the bottom has fallen out of the lower end jobs, especially in bigger cities, says Baum-Snow.

"Something fundamental has changed in our economy, and it's happening at the metropolitan level," explains Baum-Snow. While wages have always run higher in cities, prior to 1979, wage inequality was roughly equal regardless of where workers resided. Not so today. Now the local economy – specifically the size of the metropolitan area – predicts wage inequality, the study finds.

"There is a lot of concern in general about the growing disparity between the highest and lowest paid workers," explains Pavan. Today's typical CEO's brings home 300 times more than the average wage earner, 10 times more than in the 1970s. According to the Central Intelligence Agency's Gini index, this disparity puts the United States last among Western industrialized nations for wage equality.

Analysts often blame the demise of unions and the declining value of the minimum wage for widening the chasm between the wealthy and the poor. But the study shows that higher incomes in cities account for most of the wage gap. Income inequality continued to skyrocket after 2000, even as union strength remained steady during the last decade, says Baum-Snow. Likewise, the decline in the value of the minimum wage does not account for the tremendous growth in wage inequality among the upper half of the pay scale.

"If we want to understand what's causing the wage gap, we now know we need to look at the unique economies of our larger cities," says Pavan.

These metropolitan areas have created "agglomeration" economies that have augmented productivity in dramatic ways, making workers more valuable and therefore able to command higher pay, says Pavan.

For example, he says, populous regions have been able to support advanced technologies and industries that would be impractical or impossible in smaller communities and rural areas and workers have more opportunities to learn advanced skills and are exposed to innovation more rapidly. As financial centers, larger cities also have easier and cheaper access to capital for bankrolling new ventures. In fact, the study looked at the changing mix of industry in communities of different sizes and found that the industrial composition of large cities, which changed significantly over the three decades, accounted for up to one-third of the urban wage premium.

By contrast, the economies of rural areas remained relatively static over the same period. Based on this insight, the authors also calculated what the growth in the wage gap would have been had cities mimicked the slower pace of technological change in rural areas. The conclusion? The nationwide rise in wage inequality "would have been significantly less rapid if such agglomeration economies did not exit," the authors write.

The authors also examine whether higher urban wages simply reflect a clustering of highly skilled people in these geographic regions. Not according to the data, say Pavan and Baum-Snow. Although college graduates do make up a higher percentage of workers in large cities, the authors found little evidence that migration to larger cities accounted for surging urban wages.

Provided by University of Rochester