What swims beneath -- and what doesn't

(PhysOrg.com) -- Several times over the last four summers, Rutgers marine scientists have combined high and low technology to answer a straightforward scientific question: How do the fish in a big urban estuary react to big piers built by their human neighbors?

Since the early 1990s, Ken Able, a fish biologist and professor of marine science in Rutgers’ Institute of Marine and Coastal Sciences (IMCS), has studied this question in the Hudson River estuary. Most recently, he and his colleague Thomas Grothues, an associate research professor, have focused their attention on the piers jutting into the river from the west side of Manhattan.

They’ve concluded that fish that hunt by sight - striped bass, for instance - like pilings and beams, but don’t like what Able calls “intense shading” caused by large piers. Fish that don’t depend on sight but use other senses to find food - eels, or tomcod - find the water under piers more congenial. Their findings will be put into reports for the Hudson River Foundation and the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, which paid for their most recent work.

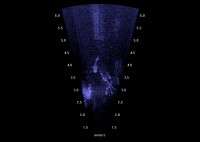

Able has been studying the behavior of fish around piers and the deckless pilings where piers once stood on both sides of the Hudson for nearly two decades. He’s used low-tech tools - nets, boats, and kayaks - to understand how fish interact with piers. They’ve also used high technology - most recently, dual-frequency identification sonar, or DIDSON. As its name implies, this sonar uses two frequencies instead of one, and so produces more acoustic information, which makes for more detailed images.

Able’s researchers load a small boat with a kayak, the DIDSON, batteries, and a laptop computer in Jersey City. They motor to Pier 40 in Manhattan, at the end of Houston Street - a great, square structure, now home to soccer fields and little league diamonds, among other facilities.

Once at Pier 40, the team attaches the DIDSON device to the kayak’s hull and a battery pack in the kayak’s stern. A researcher sits amidships, holding the paddle and facing a laptop computer attached to the DIDSON. He or she paddles under the pier, between the pilings, as far as possible (cross beams prevent the researcher from paddling all the way), recording acoustic images, and then turns and comes back to open water. The process is repeated until six representative sections at different depths have been covered.

Though they’ve been under dozens of piers over the years, the estuary still holds surprises. Able said that he and Grothues were amazed at the variety and abundance of fish in what many people assume is a polluted system.

“Well it is polluted, but it’s recovering,” Able said. “We see blues, menhaden, and lots of prey species. And we see striped bass, big and little ones - and when I say big, I mean three-footers.”

Provided by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey