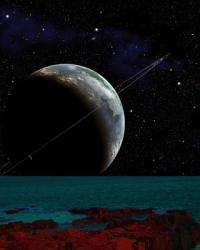

This artist's conception shows a hypothetical twin Earth orbiting a Sun-like star. Credit: David A. Aguilar (CfA)

As telescopes become more advanced, we’ll be able to see more details about planets orbiting other stars - including indications that those planets have life. However, it would probably take many centuries before we could actually see the aliens.

Although our telescopes will likely become good enough to detect signs of life on exoplanets within the next 100 years, it would probably take many centuries before we could ever get a good look at the aliens.

"Unfortunately, we are perhaps as far away from seeing aliens with our own eyes as Epicurus was from seeing the first other worlds when, 23 centuries ago, he predicted the existence of these planets," said astrobiologist Jean Schneider at the Paris Observatory at Meudon. He and his colleagues discussed the difficulties of studying distant alien life in the journal Astrobiology.

Schneider and his colleagues say that in the next 15 to 25 years, there will likely be two generations of space missions able to analyze exoplanets in greater detail. The first generation will feature 1.5-to-2.5-meter-wide coronagraphs to block out the direct light from a star to help search for giant planets and nearby super-Earths. The second generation will feature interferometers, coronagraphs and other equipment to better analyze the light reflected off these exoplanets. These missions could reveal what the planets might look like, and what they might have in their atmospheres or on their surfaces. At the same time, there will likely be coronagraphic cameras on extremely large ground-based telescopes.

After these projects, future missions could search for more potentially habitable planets either by peering at more distant stars more than 50 parsecs away or at rocky moons of giant planets seen in the habitable zones of nearby stars. The follow-up missions also could deeply investigate any exoplanets that display potential signs of life. Such missions will require much larger arrays in space — for instance, taking a 100-pixel image of a planet twice the width of Earth some 16.3 light years away would require the elements making up a space telescope array to be more than 43 miles apart.

Such pictures of exoplanets could make out details such as rings, clouds, oceans, continents, and perhaps even hints of forests or savannahs. Long-term monitoring could reveal seasonal shifts, volcanic events, and changes in cloud cover. One might even detect the presence of moons by shadows they project on the planets. More sensitive instruments could hunt for the wavelengths of infrared light associated with carbon dioxide, which could tell a lot about the atmosphere.

Beyond conventional signs of life as we know it, such as oxygen in atmospheres, another type of signal could be "technosignatures," features that cannot be explained simply by complex organic chemistry. Technosignatures could include laser light, chlorofluorocarbon gases, or even artificial constructions.

"Looking for aliens is philosophically important — it would tell us what is essential in the human condition," Schneider said.

The closest star system to the Sun is the Alpha Centauri system. Alpha Centauri A, also known as Rigil Kentaurus, is the brightest star in the constellation of Centaurus and is the fourth brightest star in the night sky. Alpha Centauri A is the same type of star as our Sun, causing many to speculate that it might host planets that harbor life. Credit: STSci Digitized Sky Survey, Anglo-Australian Observatory

However, if scientists actually detect signs of life, it will frustratingly take many centuries before humanity can realize the hope of seeing what these aliens might actually look like, Schneider and his colleagues explained.

"It is very disappointing," Schneider said.

To begin imaging even giant organisms 30 feet long and wide on the closest putative exoplanet, Alpha Centauri AB b, some 4.37 light years away, the elements making up a telescope array would have to cover a distance roughly 400,000 miles wide, or almost the Sun's radius. The area required to collect even one photon a year in light reflected off such a planet is some 60 miles wide. To determine if the lifeform is moving with a speed of even 2 feet per minute — and that the motion you’re seeing is not due to errors in observation — the area required to collect the needed photons would need to be some 1.8 million miles wide.

The only alternative would be to dispatch spacecraft out to the planet, but such a journey would be long and perilous. At speeds of 30 percent the speed of light, a 100-micron-thick interstellar grain roughly the width of a human hair would pack roughly as much kinetic energy as a 100-ton body traveling 60 miles per hour. No currently available technology could protect against such a threat without a spacecraft massing hundreds of tons, which in turn would be extraordinarily difficult to accelerate up to high speeds. One could instead travel more slowly and thus more safely, but at even 1 percent the speed of light (or about 1,860 miles per second) it would take millennia for the spacecraft to reach its target destination.

This artist's conception shows a hypothetical ringed super-Earth as viewed from one of its moons. Both super-Earth and moon are habitable and contain liquid water. Credit: David A. Aguilar, CfA

Regardless of the approach, it seems it will take centuries to get direct visual contact with any nearby aliens, at least in the framework of the science and technology we have now. What physics we might have in a millennium is not reasonable to anticipate, the researchers said.

"I hope that there will be an unpredictable revolution in physical concepts," Schneider quipped.

Not everyone found these prospects disappointing.

"We have always been planning on detecting life indirectly, by searching for atmospheric signatures of life, most likely of the single-cell variety," said astrobiologist Alan Boss at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, who did not take part in this study. "That is what we have been hoping for, and we are still a long way from being able to achieve even that modest goal. We will be overjoyed when we are able to accomplish that goal — it is a race with our planetary colleagues to see if they can find evidence for life on Mars before we find evidence for life outside the solar system!"

Of course, there’s always a chance we’ll get to study aliens close-up if they come seeking us, rather than the other way around. According to Boss, however, that is an unlikely event.

"We do not need to worry about aliens coming to Earth to enslave us — interstellar travel by living creatures is science fiction, not science fact," he said. "No one needs to worry at night about the interstellar air raid sirens going off."

Source: Astrobio.net