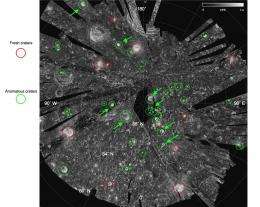

A Mini-SAR radar map of the lunar north pole. Craters circled in green are believed to contain significant deposits of frozen water.

Moonwater. Look it up. You won't find it. It's not in the dictionary.

That's because we thought, until recently, that the Moon was just about the driest place in the solar system. Then reports of moonwater started "pouring" in - starting with estimates of scant amounts on the lunar surface, then gallons in a single crater, and now 600 million metric tons distributed among 40 craters near the lunar north pole.

"We thought we understood the Moon, but we don't," says Paul Spudis of the Lunar and Planetary Institute. "It's clear now that water exists up there in a variety of concentrations and geologic settings. And who'd have thought that today we'd be pondering the Moon's hydrosphere?"

Spudis is principal investigator of NASA's Mini-SAR team - the group with the latest and greatest moonwater "strike." Their instrument, a radar probe on India's Chandrayaan-1, found 40 craters each containing water ice at least 2 meters deep.

"If you converted those craters' water into rocket fuel, you'd have enough fuel to launch the equivalent of one space shuttle per day for more than 2000 years. But our observations are just a part of an even more tantalizing story about what's going on up on the Moon."

It's the story of a lunar water cycle, and it's based on the seemingly disparate - but perhaps connectable - results from Mini-SAR and NASA's recent LCROSS mission and Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3 or "M-cubed") instrument also on Chandrayaan-1.

"So far we've found three types of moonwater," says Spudis. "We have Mini-SAR's thick lenses of nearly pure crater ice, LCROSS's fluffy mix of ice crystals and dirt, and M-cube's thin layer that comes and goes all across the surface of the Moon."

On October 9, 2009, LCROSS, short for Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, struck water in a cold, permanently dark crater at the lunar south pole. Since then, the science team has been thoroughly mining their data.

"It looks as though at least two different layers of our crater soil contain water, and they represent two different time epochs," explains Anthony Colaprete, LCROSS principal investigator. "The first layer, ejected in the first 2 seconds from the crater after impact, contains water and hydroxyl bound up in the minerals, and even tiny pieces of pure ice mixed in. This layer is a thin film and may be relatively 'fresh,' perhaps recently replenished."

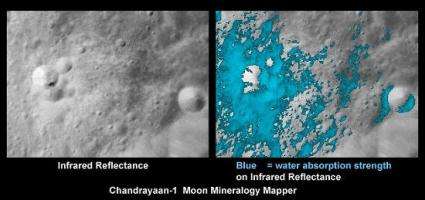

Shown in false-color blue, a thin layer of water-rich minerals cover an expanse of terrain around a young lunar crater. Credit: Chandrayaan-1/Moon Mineralogy Mapper.

According to Colaprete, this brand of moonwater resembles the moonwater M3 discovered last year in scant but widespread amounts, bound to the rocks and dust in the very top millimeters of lunar soil.

The second layer is different. "It contains even more water ice plus a treasure chest of other compounds we weren't even looking for," he says. "So far the tally includes sulfur dioxide (SO2), methanol (CH3OH), and the curious organic molecule diacetylene (H2C4). This layer seems to extend below at least 0.5 meters and is probably older than the ice we’re finding on the surface.”

They don't know why some craters contain loads of pure ice while others are dominated by an ice-soil mixture. It's probably a sign that the moonwater comes from more than one source.

"Some of the water may be made right there on the Moon," says Spudis. "Protons in the solar wind can make small amounts of water continuously on the lunar surface by interacting with metal oxides in the rocks. But some of the water is probably deposited on the Moon from other places in the solar system."

A plume of water-rich vapors billows up from crater Cabeus on Oct. 9, 2009, after LCROSS's Centaur booster hit the crater floor.

The Moon is constantly bombarded by impactors that add to the lunar water budget. Asteroids contain hydrated minerals, and comet cores are nearly pure ice.

The researchers also think that much of the crater water migrates to the poles from the Moon's warmer, lower latitudes. "All our findings are telling us there's an active water cycle on the Moon," marvels Colaprete.

Think about it. The "driest place in the solar system" has a water cycle.

"It's a different world up there," says Spudis, "and we've barely scratched the surface. Who knows what discoveries lie ahead?"

Moonwater. Add it to the dictionary.

Source: Science@NASA, by Dauna Coulter