Nanodragsters hit the street: Scientists roll agile hot rod out of micro-garage (Update)

(PhysOrg.com) -- Chemists are getting better at building nanomachines, but Rice researchers continue to race ahead of the pack.

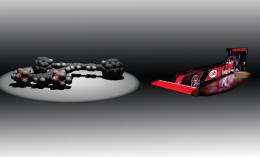

The latest work in a series of molecular machines that began with 2005's nanocar has produced what Rice University scientists James Tour and Kevin Kelly call a nanodragster for its characteristic hot-rod shape, with small wheels on a short axle in the front and large wheels on a long axle in the back.

Their research, reported in the American Chemical Society journal Organic Letters, is another step toward functional nanomachines that can be custom-built and set to work in microelectronics and other applications. Guillaume Vives, a postdoctoral research associate in Tour's lab, and JungHo Kang, a graduate student in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, co-authored the paper.

What those wheels are made of matters most. Early nanocars rolled on simple carbon 60 molecules, aka buckyballs. But they were a drag, literally, as they would only turn on a gold surface in high heat, about 200 degrees Celsius.

Tour, Rice's T.T. and W.F. Chao Chair in Chemistry and a professor of mechanical engineering and materials science and of computer science, and his team found in previous research that wheels made of p-carborane, a cluster of carbon and boron atoms, operate at much lower temperatures. But they're more difficult to image with a scanning tunneling microscope because of their much weaker interaction with metallic surfaces.

The key to making nanodragsters, Tour said, was putting p-carborane wheels in the front and buckyballs in the back, getting the advantages of both. The front wheels roll easier, while the buckyballs grip the gold roadway well enough to be imaged by Kelly, an associate professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Rice. And the vehicle operates at a much lower temperature than previous nanovehicles.

"The trick to making these nanocars was to attach the smaller wheels first, then deactivate their reactive ends through carbon group attachments that we called 'scythes,' much like blades on the centers of classical chariot wheels," Tour said. "Then we could affix the larger C60 wheels to the rear axle."

The tiny hot rod, 1/25,000th the width of a human hair, has a chassis that rotates freely and allows the car to turn when one front wheel or the other is lifted, a behavior not seen in previous nanocars. Much to the researchers' amusement, in several of the images the nanodragsters appear to be "popping wheelies" with both front wheels raised off the surface, just like real dragsters at the start of a race.

Imaging at different temperatures to better understand the energy barriers associated with moving nanovehicles is not discussed in this paper, but the researchers are undertaking such work both on the original gold surfaces and on glass and other substrates. Obtaining greater control of their motion is also the subject of ongoing research.

More information: "Molecular Machinery: Synthesis of a 'Nanodragster'", pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ol902312m

Provided by Rice University