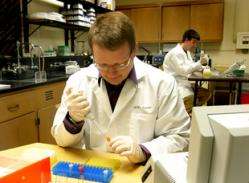

Eric Linton, assistant professor of biology at Central Michigan University, (foreground) prepares euglenoid plastid DNA samples to produce a polymerase chain reaction, a method of producing many copies of DNA from a single copy so that Linton can sequence its DNA. Undergraduate Stephen Dawson works in the background. Credit: Robert Barclay, Central Michigan University

Roughly 2 1/2 billion years ago, some algae began to photosynthesize, an astonishing development that led to the creation of plants and a myriad of complex life forms, including, incidentally, mankind.

Today, Eric Linton, a Central Michigan University assistant professor of biology, is studying the gene makeup of single-celled euglenoids — organisms that acquired the ability to photosynthesize from algae — to learn whether that evolutionary step was a single hallmark moment or a series of events over time.

Eventually, Linton hopes to learn whether dormant genes that once controlled photosynthesis in certain euglenoids can reactivate, shedding light on whether scientists can jumpstart long-dormant genes in other organisms, such as in humans to fight a host of diseases.

With a $354,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, Linton has begun a three-year project to perform complete genome sequencing of six forms of euglenoids, some of which long ago lost the ability to photosynthesize.

A focus of Linton’s research is chloroplasts — components of euglenoid cells that serve as an engine for photosynthesis, or the synthesis of sugar from light, carbon dioxide and water. Some of the euglenoids under study have functioning chloroplasts, enabling photosynthesis; in others, the chloroplasts apparently are dormant.

By examining the genes for chloroplasts from six different euglenoids, Linton hopes to learn whether all acquired the ability to photosynthesize from the same ancestor, or multiple ancestors. Also, Linton wants to deduce how the genes are transferred, lost or evolved when two genomes are combined.

The discovery of supposedly dormant genes in the euglenoids raises questions about whether such genes — both in euglenoids and humans — can receive a man-made jump-start one day.

“If they are keeping these genes around,” Linton said, “they must be achieving something.”

Most genome sequencing will occur off-campus, but Linton plans on using a $50,000 differential interference contrast microscope — which provides near 3D imaging — for much of the study. A graduate student and two undergraduates will assist him.

Source: Central Michigan University