Discovering the source of long-term motor memory

The motor memory we use everyday-for sport, playing a musical instrument and even typing-is acquired through repeated practice and stored in the brain. New motor skills can be learned through practice, but often those skills can be all but lost by the following day. This loss of motor skills can be attributed to the storage of newly learned motor skills in short-term memory. By repeating the exercises on a daily basis, however, these skills become stored in long-term memory.

In 2006, a team led by Soichi Nagao, head of the Laboratory for Motor Learning Control at the RIKEN Brain Science Institute (BSI), discovered that short-term motor memory is transferred to a different site to become long-term memory, and that brain activity while the body is at rest is important for creating long-term memory-more so than the brain activity while the body is working. With this discovery, research into the mechanism of motor memory is now breaking new ground.

Settling a 40-year debate

The mechanism of memory was originally attributed to changes in the transmission efficiency of synapses in the brain. Around 1970, it was proposed that motor memory specifically was created within the neural network of the cerebellum. One of the advocates of this theory was Masao Ito, senior advisor to the BSI. In 1982, Ito experimentally discovered the phenomenon of 'long-term depression', by which the transmission efficiency in the cerebellum is depressed over a long period of time.

In 1983, Nagao started work as a laboratory lecturer for Ito, who was then a professor in the Faculty of Medicine at The University of Tokyo. "Since then, I have continued my studies to verify and develop the theoretical hypothesis proposed by Dr. Ito and other researchers," says Nagao.

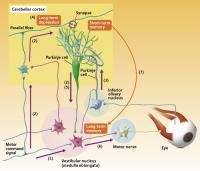

The process of eye movement is a good illustration of how the hypothesis proposed by Ito works (Figs. 1, 2). Command signals that control eye movement are transmitted to the vestibular nucleus in the medulla oblongata over two routes: one direct and the other indirect passway via the parallel fibers and Purkinje cells of the cerebellar cortex. The vestibular nucleus processes the command signals transmitted over both routes and outputs the processed signals to the motor nerves, which in turn, control the movement of the eye.

A single Purkinje cell is connected to up to 200,000 parallel fibers, through which command signals to control movements are transmitted to the Purkinje cell. A single climbing fiber is connected to the Purkinje cell, and when an eye fails to move properly, error signals are transmitted from the eye to the Purkinje cell through an inferior olivary nucleus and the climbing fiber. This process triggers long-term depression, suppressing the transmission efficiency of the command signals at the synapses connecting the parallel fibers to the Purkinje cell. When the eye moves properly, no long-term depression is triggered because the error signals are low. In this way, command signals from the Purkinje cell to the vestibular nucleus can change dynamically because of the long-term depression induced in response to eye movement.

"Command signals from the vestibular nucleus to the motor nerves are controlled so that the eye can move properly," says Nagao. "In other words, Dr. Ito's theory states that motor memory is created in Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex through long-term depression."

Purkinje cells in the evolutionarily oldest region of the cerebellar cortex-the vestibulocerebellum-have axons that extend to the vestibular nuclei, whereas Purkinje cells in the newer region-the archicerebellum and neocerebellum-have axons that extend to the deep cerebellar nuclei to form neural circuits.

"Doctor Ito's hypothesis is controversial and has been debated for about 40 years. A typical argument runs as follows: it is true that Purkinje cells are capable of transmitting the information necessary for motor memory, but the memory is created in the vestibular or cerebellar nuclei."

The source of long-term motor memory

In 2006, Nagao published an article that finally settled the dispute over where motor memory is created: in Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex, or in the vestibular or cerebellar nuclei? The achievement came just two years after he established the Laboratory for Motor Learning Control at the RIKEN BSI in 2004. Nagao and his laboratory members developed a new experimental system using mice to examine the memory of eye movement. One of the mechanisms of eye movement allows us to track objects reflexively, like when watching the passing view from a train window. If this mechanism, known as optokinetic eye movement response, is working properly, the view is clear and we can see passing objects. The memory function of the optokinetic eye movement response can be evaluated by placing a checkered screen in front of a mouse and moving it in a wave-like manner.

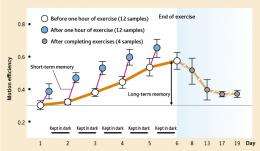

"The mouse will get used to the movement in about an hour of exercise and will be able to follow the movement of the checkered screen by moving its eyes in a wave-like motion. This is because motor memory has been created, and the eye movement efficiency of the mouse has improved. However, when the mouse is kept in a dark room after the exercise, and when the eye movement efficiency is examined the next day, you will find the efficiency has returned to the initial state."

Even when motor memory has been established after one day of exercise, most memory is lost within several hours. This is because only short-term memory is created in the first instance, but this can be improved on (Fig. 3). "A mouse can gradually improve its eye movement efficiency when we get the mouse to do exercises on a daily basis. A mouse that has done such exercises for one week can maintain its eye movement efficiency at a higher level than before it started, even after the exercises have been terminated. This means that long-term memory has been established."

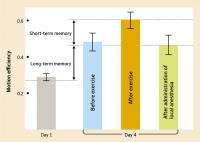

However, it was still unknown whether these short- and long-term motor memories are created in Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex or somewhere else. "To stop the function of the cerebellar cortex, we administered local anesthesia to the cerebellar cortex of a mouse that had repeated specific exercises for four days and examined the eye movement efficiency of the mouse. We found that the efficiency remained at the same level as when the exercise was started on the fourth day. In other words, the previous three days had contributed to improving the eye movement efficiency and the efficiency then remained at that level, indicating that long-term memory was created at a site other than in the cerebellar cortex." The exercise on the fourth and subsequent days, on the other hand, did not add to improving the eye movement efficiency, indicating that short-term memory was created in Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex (Fig. 4).

Nagao and his team then conducted experiments to confirm whether long-term memory is created in the vestibular nucleus. "We discovered that no motor memory is created in either the cerebellar cortex or the vestibular nucleus alone, but that short- and long-term memories are created at different sites: short-term memory in Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex and long-term memory in the vestibular nucleus. Around the time we published these experimental results, other research groups also reported similar results using different models. That is how we succeeded in settling the 40-year debate."

Neither short- nor long-term memory is created when the functioning of the cerebellar cortex is impeded. "Motor memory is initiated by short-term memory by long-term depression in Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex. Short-term memory becomes long-term memory when it is transferred in one way or another to the vestibular nucleus, into which axons extend from the Purkinje cells. Long-term memory is considered to be created in neural circuits in the vestibular or cerebellar nuclei, into which axons extend from the Purkinje cells.

Long-term motor memory is not made for sophisticated motion

It is thought that information that can be expressed verbally, such as experienced events and the spelling of English words, is stored in the hippocampus, deep in the cerebrum, as short-term memory, and is later transferred to the cerebral cortex to become long-term memory. "The short-term memory of effable information is not immediately transferred to the cerebral cortex, but stays in the hippocampus for a few weeks. We have clarified that short-term motor memory created in Purkinje cells in the cerebellar cortex is transferred to the vestibular or cerebellar nuclei in as little as several hours or as long as several days."

However, it has become clear that not all information in short-term motor memory becomes long-term motor memory. Nagao and his team used monkeys to investigate how sophisticated motion is memorized. In the experiment, the speed of a moving ball is suddenly increased for a fifth to a tenth of a second. "In this experiment, monkeys are required to follow the complex motion of the ball, called 'smooth-pursuit eye movement'. Monkeys usually get used to the motion only after the exercise has been repeated a few dozen times, moving their eyes based on their prediction of the change in the speed of the ball. However, sophisticated motor memory of this kind is easily lost in just ten to 15 minutes. In other words, the memory of sophisticated motion is stored quickly but also lost quickly. One major advantage in terms of short-time memory in the cerebellar cortex is that sophisticated motion can be memorized very quickly." For example, a baseball batter will be able to hit a curve ball after the movement of the ball has been observed several times and memorized. Unfortunately, however, it has become clear that sophisticated motor memory of this kind hardly ever becomes long-term memory because only the broad information in short-time memory is transferred to long-term memory.

"It is said that skills that are learned physically cannot really be forgotten. For example, once you have learned how to ride a bicycle, you will be able to ride a bicycle again with a little practice even after a long period without riding. We can consider long-term motor memory to be robust and difficult to forget. However, we should respect the importance of 'a little practice' because long-term motor memory only holds rough or broad information. We need to activate the functions of the cerebellar cortex by memorizing sophisticated movement to get the 'feel' for the movement. I do not think that any professional musicians would be able to show their abilities at a concert without practicing beforehand."

There are evolutionary reasons why short- and long-term memories are created at different sites in the brain. "Keeping specific sophisticated motor information in the cerebellar cortex for a long time would make it difficult to adapt movements quickly in response to environmental changes. I think that transferring only basic motor information to the vestibular or cerebellar nuclei as long-term memory ensures that sophisticated movements will always be stored in the cerebellar cortex and remain adaptable in response to changing situations." All vertebrate animals, from fish to mammals, have the same mechanism of short- and long-term motor memory storage at different sites. Invertebrate animals, however, are known to store short- and long-term motor memories at the same site in their neural circuits. "This difference is one of the features that differentiate vertebrate animals from invertebrates."

Interval training for long-term memory

The mechanism of how short-term memory in the cerebellar cortex is transferred to the vestibular or cerebellar nuclei to become long-term memory is still open for debate.

"Making use of a variety of techniques, we are working towards answering the question." Recently, Nagao and his team discovered that short-term memory is transferred efficiently to long-term memory when experiments on motor memorization using animals are conducted with intervals between the exercises rather than conducting the experiment continuously. "For example, a one-hour experiment can be divided into four short 15-minute exercises with intervals of 30 minutes between them for higher transfer efficiency. We also discovered that no long-term memory is created irrespective of the number of repeated exercises if the functions of the cerebellar cortex are deactivated during those intervals."

These findings suggest that the activities of the cerebellar cortex during periods of inactivity are important in creating long-term memory. This presents the question of what happens in the cerebellar cortex during the intervals to cause long-term memory to be created in the vestibular or cerebellar nuclei. "We have not yet obtained experimental data that can lead us to a conclusion. However, we are beginning to collect important data that suggest the importance of 'long-term potentiation', which enhances the transmission efficiency of synapses, for long-term memory creation."

Coachly advice

Nagao's research provides some valuable pointers as to how to improve sporting and performance skills. "The key is to repeat exercises, with intervals, on a daily basis. Top athletes and musicians will be more talented than ordinary people in creating short-term and long-term memories. Motor memory, however, is not created without repeated exercise. I think even someone who is thought of as a genius needs to continue daily exercises because motor information on sophisticated movements is difficult to establish as long-term memory."