Microbial protein restores vision in blind animals

(PhysOrg.com) -- Scientists from the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research (FMI) restore vision in retinitis pigmentosa using an archaebacterial protein. Introducing halorhodopsin into the remaining but nonfunctional cone photoreceptors of the retina of mice not only reactivates the cone cells' ability to interact with the rest of the visual system, it also prompts sophisticating visually guided behavior.

With their collaborators in the Vision Institute of Paris, the scientists were able to validate their results in light-insensitive human retinas in vitro, which were able to respond to light again after treatment. These groundbreaking results were published today in the journal Science.

Retinitis pigmentosa is a diverse group of hereditary diseases that lead to incurable blindness and affect two million people worldwide. Despite the diversity of its cause, the manifestation of the disease is similar: the highly sensitive rod photoreceptors, which allow us to see in the dusk, die. Intriguingly, the cones that operate during daylight and are responsible for high-resolution color vision survive longer, though they gradually lose their function. However, it was unknown if these persisting photoreceptors would be accessible for therapeutic intervention.

Neurobiologists from Botond Roska's group at the Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, which is part of the Novartis Research Foundation, now have devised a gene therapeutic method to restore the functionality of the cone cells in models of retinitis pigmentosa. In a groundbreaking approach they used a light-sensitive protein called halorhodopsin from archaebacteria to re-establish vision.

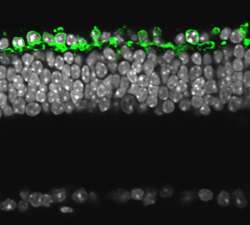

In their work, featured today in the reknown journal Science, they were not only able to specifically produce halorhodopsin in the dormant cone cells of mice with retinitis pigmentosa, but they could also show that the cones were able to interact with the rest of the visual system. The existing network of cells was able to reproduce many of the functions of the complicated cascade of molecular events that turn a unit of light into a neuronal signal. What is more, behavioral tests indicated that the retinal information was used for visually guided behavior. The remaining cone cells are therefore an optimal target for gene-therapeutic intervention in disease where photoreceptor function is lost.

As a first step to translate these findings to patients, together with their collaborators from the Vision Institute of Paris, the FMI group introduced the archaebacterial halorhodopsin into nonfunctional human cone cells. And these treated cones in isolated human retinas started to respond to light.

"We believe that with our gene therapeutic method we have found a powerful approach that could eventually help a subset of retinitis pigmentosa patients. Our colleagues in Paris are screening patients to determine who may benefit most from this approach," comments Botond Roska.

More information: Busskamp V, Duebel J, Balya D, Fradot M, Viney JT, Siegert S, Groner AC, Cabuy E, Forster V, Seeliger M, Biel M, Humphries P, Paques M, Mohand-Said S, Trono D, Deisseroth K, Sahel JA, Picaud S, Roska B.(2010) Genetic Reactivation of Cone Photoreceptors Restores Visual Responses in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Science, DOI:10.1126/science.1190897