Kepler has caught hundreds of asteroids

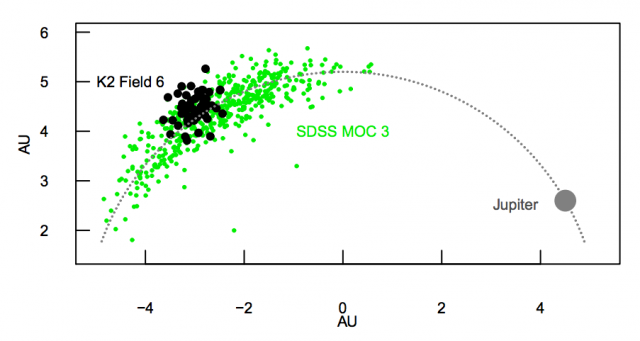

Previously, the Kepler space telescope looked straight out from the solar system in a direction almost perpendicular to the ecliptic and the plane of the planets. This way, it could observe the same spot all year long, as the sun, and most of the solar system, were out of its field of view. But since the start of K2 mission, it has been observing parallel to that plane in order to better balance against the radiation pressure of the sun. This new strategy has two important consequences: One is that Kepler has to change its field of view every three months to avoid the sun; the other is that our own solar system, unexpectedly, has become a target for the exoplanet-hunting telescope.

For most astronomers working with Kepler, planets and asteroids zipping through the images are little more than a nuisance when studying the light variations of stars. Researchers from the Konkoly and Gothard Observatories in Hungary, however, saw a research opportunity in these moving specks of light. Following up on their work with trans-Neptunian objects, they examined the light variations of some main-belt and Trojan asteroids in a pair of research papers. They used a custom-built pipeline based on the software package Fitsh, developed by team member András Pál, to accurately measure moving targets in the images.

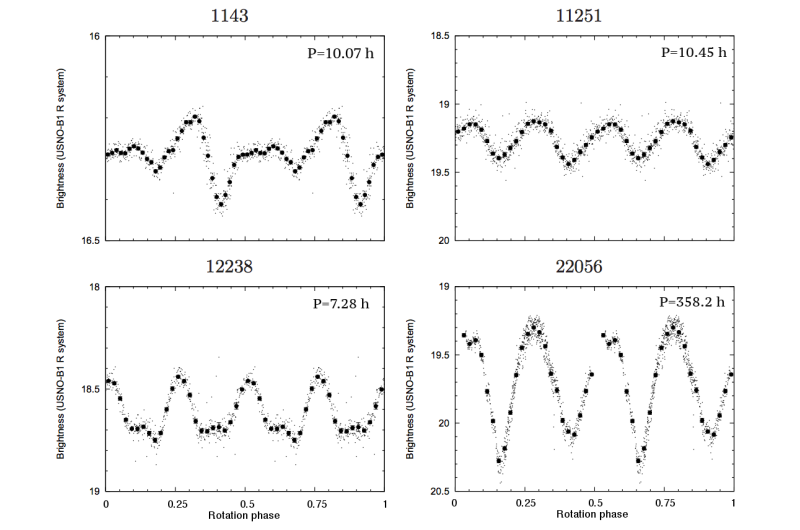

Main-belt asteroids were not targeted by Kepler, so the astronomers selected two extended mosaics that covered the open cluster M35 and the path of the planet Neptune, and simply tracked all known asteroids crossing them. Most of the objects were continuously observable for one to four days, which may not sound like much, but is significantly longer than single-night runs achievable with ground-based telescopes. Indeed, the researchers hoped that with Kepler, they could determine the rotation periods of the asteroids more accurately, without the uncertainties caused by daytime gaps in the data—and they did, but only for a fraction of the sample.

"We measured the paths of all known asteroids, but most of them turned out to be simply too faint for Kepler. The dense stellar background toward M35 further reduced the number of successful detections," said Róbert Szabó (Konkoly Observatory, MTA CSFK), lead author of the paper. "Still, we have to keep in mind that Kepler was never meant to do such studies; therefore, observing four dozen asteroids with new rotation rates is already more than anybody anticipated," he added.

The other study focused on 56 pre-selected Trojan asteroids in the middle of the L4, or "Greek" group, which orbits ahead of Jupiter. Since they are farther out from Kepler, they could be observed for longer periods, from 10 to 20 days, without interruption. And this turned out to be crucial: Many objects exhibited slow light variations between two and 15 days. Long periodicity suggests that what we see is not just one rotating asteroid, but actually two orbiting each other—the study confirmed that about 20 to 25 percent of Trojans are binary asteroids or asteroid-moon pairs. As Gyula M. Szabó (ELTE Gothard Astrophysical Observatory), lead author of the other paper, said, "Estimating the rate of binaries highlights the great advantage of Kepler, because the interesting periods, longer than 24 to 48 hours, are really hard to measure from the Earth."

What Kepler did not see are rapidly spinning Trojans. Even for the fastest ones, one rotation takes more than five hours, suggesting that the asteroids we see are likely icy, porous objects, similar to comets and trans-Neptunian objects, and different from the rockier main belt objects. "A large piece of rock can rotate much faster than a rubble pile or an icy body of the same size without breaking apart. Our findings favour the scenario that Trojans arrived from the ice-dominated outer solar system instead of migrating outwards from the main asteroid belt," Szabó said.

As Kepler continues its new mission, more objects from the solar system are crossing into its view, including planets, moons, asteroids and comets. The telescope that transformed the science of stars and exoplanets will undoubtedly leave its mark in planetary science, as well.

More information: Szabó, R., et al: Uninterrupted optical light curves of main-belt asteroids from the K2 Mission, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2016), dx.doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201629059, arxiv.org/abs/1609.02759

Szabó, Gy. M., et al.: The heart of the swarm: K2 photometry and rotational characteristics of 56 Jovian Trojan asteroids, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2016), doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201629401, arxiv.org/abs/1609.02760

Journal information: Astronomy & Astrophysics

Provided by Konkoly Observatory