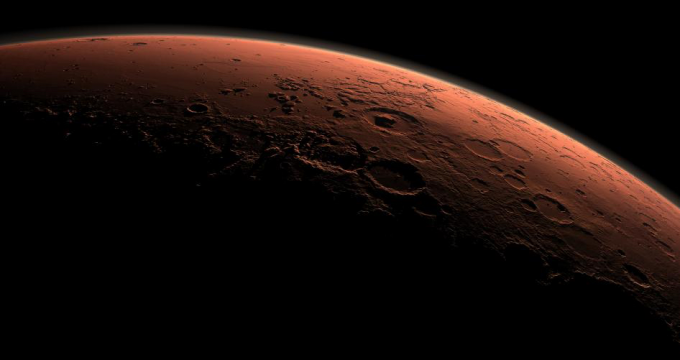

Europe heads for Mars in search of life

Thirteen years after its first, failed attempt to place a rover on Mars, Europe reaches a crucial stage Sunday in a fresh quest to scour the Red Planet for signs of life, this time with Russia.

Mission controllers will instruct a spacecraft about 175 million kilometres (109 million miles) from Earth to release and steer a paddling pool-sized lander towards the Red Planet's cold, dry surface.

Scheduled to arrive next Wednesday (October 19), the short-lived lander's sole purpose is to prepare the way for a subsequent rover which will drill into Mars in search of extra-terrestrial life.

"Our goal here is to prove we can get to the surface, do science, take data," European Space Agency (ESA) science advisor Mark McCaughrean said ahead of Sunday's lander-release manoeuvres.

Dubbed Schiaparelli, the 600-kilogramme (1,300-pound) lander will separate from its mothership, the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), after a seven-month, 496 million-kilometre (308 million-mile) trek from Earth.

The lander and the TGO—which will enter into orbit around Mars to sniff its atmosphere for gases excreted by living organisms—comprise the first phase of the joint European-Russian ExoMars project.

The second phase, due for launch in 2020 after a two-year funding delay, is the ExoMars rover, for which Schiaparelli will be testing entry and soft-landing technology.

More than half of US, Russian and European attempts to land and operate craft on the Martian surface since the 1960s have failed.

The last time Europe tried, the British-built Beagle 2 disappeared without a trace after separating from the Mars Express mothership in December 2003.

It was finally spotted in January 2015 in a NASA picture of Mars. It showed that even though Beagle 2 failed to establish contact, it had successfully landed.

What's making the methane?

The United States is alone in having successfully operated rovers on Mars.

If there is life on Mars, it is unlikely to be found on the surface, which is bombarded by ultraviolet and cosmic rays.

But scientists say traces of methane in Mars' thin atmosphere may be an indicator of something stirring underground.

Methane also does not survive the Sun's ultraviolet rays for long, McCaughrean explained.

"And so for it actually to exist in the Martian atmosphere, it must be coming from something. Something must be making methane."

One possible source is underground volcanoes.

Another is life: single-celled microbes called methanogens, which on Earth live in places without oxygen such as animal stomachs, where they convert carbon dioxide into methane.

It is hoped that the ExoMars rover—equipped to drill two-metres (six feet) below the surface—will yield some clues as to the provenance of Mars' methane.

In the meantime, Schiaparelli's exploits will be crucial in designing the rover's landing gear.

The lander will separate from the TGO around 1430 GMT on Sunday, about a million kilometres (621,000 miles) from the Red Planet.

It will enter the atmosphere on Wednesday at an altitude of some 121 km and a speed of nearly 21,000 km (13,000 miles) per hour.

The hot and bumpy trip through Mars' atmosphere will take six minutes.

To protect the lander, an "aeroshell" will absorb and dissipate the heat generated by atmospheric drag for the first three or four minutes.

When it has reached an altitude of 11 km and slowed to 1,700 km/hr, a supersonic parachute will be deployed, the ESA said.

After slowing further and jettisoning its shell and parachute, Schiaparelli will activate nine speed-control thrusters. It will briefly hover at an altitude of two metres before cutting its engines and falling to the surface.

The impact is meant to be absorbed by a crushable structure in the lander's belly—similar to a car's crumple zone.

"It is a complex mission," Thierry Blancquaert, ESA's Schiaparelli manager, told AFP. "Landing on Mars requires a lot of technology."

With a 10-minute delay—the time it takes for a message to reach Earth—Schiaparelli will send data on temperature, humidity, density profile and electrical properties.

Battery-driven and without solar panels, the lander should last for two or three days.

"Even if it does not work, we will gain a lot of information," said Michel Denis, ExoMars flight director.

"If something goes wrong, we will know what it was."

After releasing Schiaparelli, the TGO will change course to avoid crashing into Mars.

It will then start a 12-month process of "aerobraking"—skimming the Martian atmosphere to bleed off energy—to change its eccentric orbit into a circular one.

In early 2018, it will start analysing Mars' atmosphere from an altitude of about 400 km.

If Sunday's separation fails, mission controllers can try again on Monday.

Facts behind Europe and Russia's ExoMars mission

Europe and Russia will send a test lander Sunday on a one-way trip to the Martian surface, a key step in their joint ExoMars project to search for life on the Red Planet.

Some facts about the mission:

What's in a name?

ExoMars gets its name from "exobiology"—the science of analysing the odds and likely nature of life on other planets.

Schiaparelli, the lander, was named after a 19th century Italian astronomer who had observed lines on Mars through a telescope which he called "canali".

This was mistranslated into English as canal (instead of channel), which cause many to imagine vast irrigation networks built by intelligent creatures.

Better telescopes in the 20th century killed that legend.

In numbers:

The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) spacecraft, which will analyse our neighbour's atmosphere, measures 3.5 metres by two metres by two metres (11.5 feet by 6.5 feet by 6.5 feet).

It has solar wings spanning 17.5 metres, tip to tip.

With the Schiaparelli lander on board, it travelled 496 million kilometres (308 million miles) to get to Mars.

On Sunday, it will release Schiaparelli from a distance of a million kilometres.

The paddling pool-sized lander, 1.6 metres wide, will test entry and landing gear for a subsequent rover to be launched in 2020.

Why?

Scientists believe Mars once hosted liquid water—a key ingredient for life as we know it.

While the Martian surface is too dry, cold and radiation-blasted to sustain life today, this may have been a different story 3.5 billion years ago when the Red Planet's climate was warmer and wetter.

Science has long abandoned the hunt for little green men, though.

Life, if any exists, is likely underground—away from harmful ultraviolet and cosmic rays—and in the form of single-celled microbes.

Primitive or not, it would be the first time humans ever observe life on a planet other than Earth.

The mission will also seek to learn more about geological process on Mars, and about the sand storms that change the face of the planet with their seasonal violence.

How?

TGO will taste Martian gases, looking specifically for methane.

Methane is important because it may be a portender of life—on Earth it is mostly produced by biological processes.

Previous missions had already picked up traces of methane in Mars' atmosphere, but the TGO has much more sophisticated tools which scientists hope to tell whether it is biological or geological in origin.

Methane can, theoretically, also be created by underground volcanoes.

The rover will drill into Mars to look for evidence of buried, extinct life, or even live microbic activity.

Who?

While diplomatic ties between Europe and Russia may be under strain, they collaborate closely on ExoMars—a shared project of Roscosmos and the European Space Agency (ESA).

Europe has budgeted 1.3 billion euros ($1.4 billion) for the mission

America's NASA, which was due to contribute $1.4 billion, pulled out due to budget cuts in 2012, pushing Europe to turn to Russia.

Moscow agreed to provide launcher rockets in exchange for space for science instruments onboard the craft.

The lander, Schiaparelli, is European, and the rover will be too. The platform housing the rover and its science lab will be Russian.

Prestige:

"We need to demonstrate our ability to do things on our own," ESA senior scientist Mark McCaughrean told AFP of the European quest.

"Its partly about proving that Europe has the capability and the will and the power to pull these projects together."

© 2016 AFP