Runaway stars leave infrared waves in space

Astronomers are finding dozens of the fastest stars in our galaxy with the help of images from NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope and Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE.

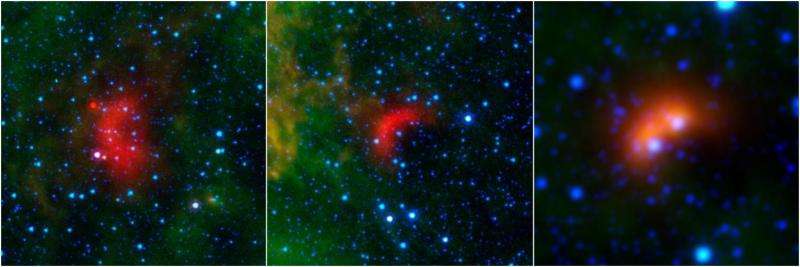

When some speedy, massive stars plow through space, they can cause material to stack up in front of them in the same way that water piles up ahead of a ship. Called bow shocks, these dramatic, arc-shaped features in space are leading researchers to uncover massive, so-called runaway stars.

"Some stars get the boot when their companion star explodes in a supernova, and others can get kicked out of crowded star clusters," said astronomer William Chick from the University of Wyoming in Laramie, who presented his team's new results at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Kissimmee, Florida. "The gravitational boost increases a star's speed relative to other stars."

Our own sun is strolling through our Milky Way galaxy at a moderate pace. It is not clear whether our sun creates a bow shock. By comparison, a massive star with a stunning bow shock, called Zeta Ophiuchi (or Zeta Oph), is traveling around the galaxy faster than our sun, at 54,000 mph (24 kilometers per second) relative to its surroundings. Zeta Oph's giant bow shock can be seen in this image from the WISE mission:

Both the speed of stars moving through space and their mass contribute to the size and shapes of bow shocks. The more massive a star, the more material it sheds in high-speed winds. Zeta Oph, which is about 20 times as massive as our sun, has supersonic winds that slam into the material in front of it.

The result is a pile-up of material that glows. The arc-shaped material heats up and shines with infrared light. That infrared light is assigned the color red in the many pictures of bow shocks captured by Spitzer and WISE.

Chick and his team turned to archival infrared data from Spitzer and WISE to identify new bow shocks, including more distant ones that are harder to find. Their initial search turned up more than 200 images of fuzzy red arcs. They then used the Wyoming Infrared Observatory, near Laramie, to follow up on 80 of these candidates and identify the sources behind the suspected bow shocks. Most turned out to be massive stars.

The findings suggest that many of the bow shocks are the result of speedy runaways that were given a gravitational kick by other stars. However, in a few cases, the arc-shaped features could turn out to be something else, such as dust from stars and birth clouds of newborn stars. The team plans more observations to confirm the presence of bow shocks.

"We are using the bow shocks to find massive and/or runaway stars," said astronomer Henry "Chip" Kobulnicky, also from the University of Wyoming. "The bow shocks are new laboratories for studying massive stars and answering questions about the fate and evolution of these stars."

Another group of researchers, led by Cintia Peri of the Argentine Institute of Radio Astronomy, is also using Spitzer and WISE data to find new bow shocks in space. Only instead of searching for the arcs at the onset, they start by hunting down known speedy stars, and then they scan them for bow shocks.

"WISE and Spitzer have given us the best images of bow shocks so far," said Peri. "In many cases, bow shocks that looked very diffuse before, can now be resolved, and, moreover, we can see some new details of the structures."

Some of the first bow shocks from runaway stars were identified in the 1980s by David Van Buren of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. He and his colleagues found them using infrared data from the Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS), a predecessor to WISE that scanned the whole infrared sky in 1983.

Kobulnicky and Chick belong to a larger team of researchers and students studying bow shocks and massive stars, including Matt Povich from the California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. The National Science Foundation funds their research.

Images from Spitzer, WISE and IRAS are archived at the NASA Infrared Science Archive housed at the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. Caltech manages JPL for NASA.

Provided by NASA